- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3952

Making the Best of Egypt’s Entrance into Somalia

The United States can help renew the African Union mission by managing Egypt-Ethiopia tensions and mediating between various actors in Somalia.

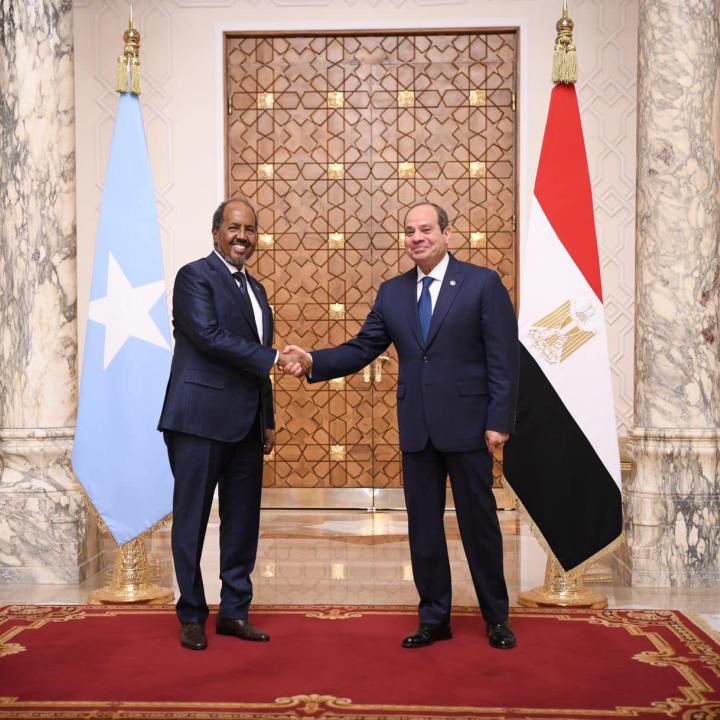

On November 3, Egypt delivered a third batch of weapons to the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) as part of a deal to arm and train the Somali National Army (SNA) and eventually deploy Egyptian troops there. The first batch (containing small arms, light weapons, and armored vehicles) came on August 27, and the second in late September.

The weapons are arriving at a time when the African Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) is set to expire at year’s end. As this mission winds down, Somalia, the African Union, and the UN have been working on its planned replacement, the AU Support and Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM), whose operational concept envisions deploying around 12,000 mostly military personnel from AU member states to continue defending the FGS against the al-Qaeda affiliate al-Shabab. Although the new mission has yet to secure the requisite funding, it is currently set to commence on January 1 and last through 2029.

Meanwhile, Ethiopia signed a deal in January with the internationally unrecognized breakaway region of Somaliland, which granted Addis Ababa a lease on twenty kilometers of its claimed shoreline in return for recognition. The agreement angered the FGS and spurred it to call for excluding Ethiopia from AUSSOM.

In addressing these issues, Washington’s priorities should be to manage tensions between Ethiopia and Egypt while securing funding for AUSSOM. This would help ensure the continuation of the AU mission, which is crucial to keeping al-Shabab from expanding its territorial control in Somalia.

Egyptian Military Engagement with Somalia

Soon after gaining independence in 1960, Somalia claimed Ethiopia’s Ogaden region as its own, fighting a two-month border war over the Somali-majority area in 1964 after an uprising broke out there. In 1977, Somalia launched a full-scale invasion of Ethiopia, though a Soviet-Cuban intervention delivered a crushing defeat that set Somalia on a long trajectory of civil strife. In both cases, Egypt provided military aid to fuel Somalia’s irredentist adventures. Yet its recent arms transfers are Cairo’s first since 1977.

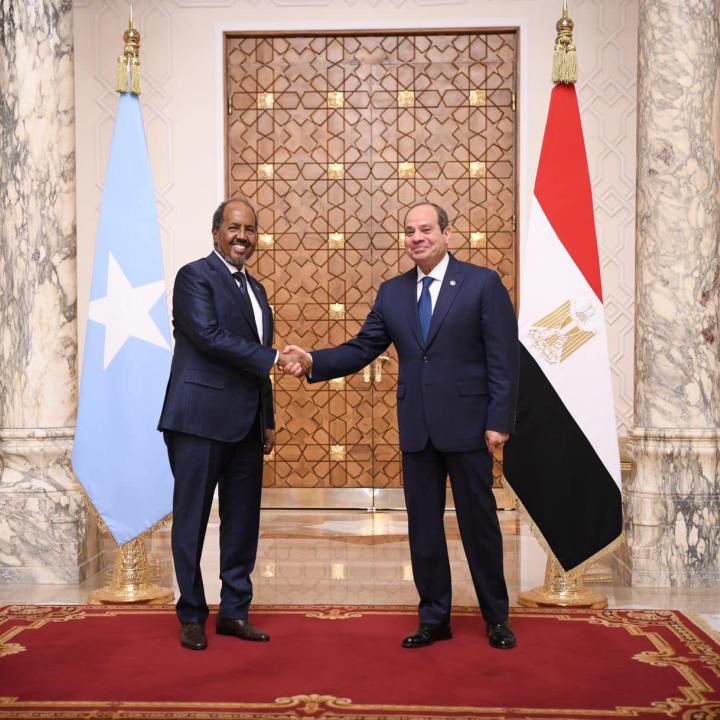

In 1993-95, Egypt contributed around 1,600 troops to support the UN Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II) peacekeeping mission after pledging a battalion to the preceding UNOSOM I. When a new FGS administration took office in 2022, however, Cairo assumed a greater role in assembling capable forces for the planned FGS offensive against al-Shabab, training up to 3,000 SNA members in Egypt since 2023. It also began providing specialized counterterrorism training for batches of fifty FGS security personnel each, and provided similar training for a program to develop a 3,500-4,500-strong military police unit funded by the United Arab Emirates.

If Cairo’s agreed deployment to Somalia goes forward, 10,000 Egyptian troops would enter the country, half of them assigned to AUSSOM. This would represent Egypt’s most extensive military support to Somalia yet, and its largest foreign deployment since the 1991 Gulf War.

Tensions with Ethiopia

Egypt and Ethiopia have disputed use of Nile River water since at least 1959, when Cairo began planning construction of the Aswan High Dam. Egypt considers the dam—operational since 1970—necessary to secure continuous use of a resource that provides almost all of its drinking water and much of its irrigation. Yet the unilateral construction angered Ethiopia and other upstream states, particularly because Egypt opposed Nile development in these states to preserve its water supply. In 2022, Addis Ababa completed its own massive water project, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which Cairo asserts will reduce the amount of water available to Egyptians.

These issues have informed Egypt’s support for Somalia since 1960, as well as parallel efforts over the years to aid Somali and Eritrean separatists. Today, Cairo likely sees its planned military deployment to Somalia as an opportunity to eject Ethiopian forces and place its own troops on the border between the two countries. This would facilitate Egyptian meddling in Ethiopia while denying its rival a forward presence in Somalia, which Addis Ababa uses to limit unrest in Ogaden and contain al-Shabab. At the same time, a deployment would open Egyptian forces to al-Shabab attacks.

Since 2006, Ethiopia has committed thousands of troops to fighting al-Shabab in Somalia. It has also comprised an essential part of AU forces, setting the groundwork for the 2007 formation of the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM, the predecessor of ATMIS) through its intervention the previous year. AMISOM liberated Somalia’s major population centers from al-Shabab and relegated the group’s territorial control to mostly rural areas. Local authorities have developed good relations with Ethiopian forces and rely on them for security.

As for Addis Ababa’s new deal with Somaliland, one of its main goals is to restore Ethiopia’s access to the sea, which the country lost in 1993 after neighboring Eritrea achieved independence. If the deal goes forward, Ethiopia would become the only UN member state to recognize Somaliland’s independence—a status that the FGS strongly opposes as a violation of its sovereignty.

U.S. Policy Recommendations

To date, U.S. policy in Somalia has focused on developing the SNA’s Danab Brigade (a special operations unit), providing military and humanitarian aid to the FGS, and conducting airstrikes and Special Forces actions to support the SNA against al-Shabab. Washington should now seek to play a convening role in organizing the next AU mission by managing tensions between contributing states, coordinating the various actors in Somalia, and helping to resolve the AUSSOM funding issue. The FGS still needs AU forces; without them, Mogadishu could fall to al-Shabab, which would certainly not be in U.S. or allied interests.

Egypt’s planned troop deployment could be an asset to AUSSOM, but only if Cairo eschews some of the harmful tactics it has employed against jihadists in the past. For example, its recent campaign against the Islamic State insurgency in the Sinai Peninsula included the destruction of the Egyptian side of Rafah on the border with Gaza, the displacement of thousands of Sinai families, and allegations of human rights abuses. Although these tactics were meant to isolate the jihadists, they pushed many locals into the Islamic State’s orbit. The jihadists’ own abuses against Sinai tribal communities eventually provided Egypt with an opening to work with key clans and root out the insurgents, with major help from Israeli air and intelligence support.

Somalia presents a new challenge, but Cairo can now learn from its shortcomings in Sinai. Going forward, Egypt must work with the FGS and local clans to improve their situation while simultaneously fighting al-Shabab—all in cooperation with capable foreign actors. In turn, the United States should leverage its diplomatic power and, if needed, its military assistance to Egypt to ensure that Cairo stays on the right path.

U.S. officials should also do what they can to preserve Ethiopia’s contribution to AU missions in Somalia and manage its tensions with Egypt. Addis Ababa has proven its value in the fight against al-Shabab, with sustained military effectiveness based on sound intelligence and intimate knowledge of the country gained through long deployment experience. Despite FGS misgivings, Ethiopia has stated that it does not intend to withdraw its 3,000 troops assigned to ATMIS or its additional thousands deployed separately.

Regarding tensions over Somaliland, the United States can work with another important partner to arrange for alternative Ethiopian access to the sea—namely, a port in Djibouti, which the latter’s foreign minister has already offered. Success on this issue could address FGS grievances with the Somaliland port deal and soften its political opposition to Ethiopia’s continued deployment.

To secure and sustain AUSSOM contributions, a new funding mechanism is needed. Since 2009, the UN Support Office for AMISOM, the UN Support Office for Somalia, and the UN Assistance Mission in Somalia have provided hundreds of millions of dollars per year to support the AU mission, mainly for logistics. The European Union has taken on much of the funding burden for AMISOM and ATMIS, contributing approximately $2.5 billion between 2007 and 2022. Yet it has reduced its contributions since 2016 and indicated less willingness to be a major AUSSOM funder. The United States should seek to renew the European role, leveraging its relations with all of the parties to increase funding while insisting on oversight measures to address EU concerns over misuse and diversion.

Washington can also seek funds from Persian Gulf countries, several of which have previously provided small donations to the Somalia mission and maintain their own operations there. For example, the past UAE-funded efforts to train SNA troops in Egypt could be renewed and expanded under AUSSOM, perhaps bringing in Saudi Arabia as well. Other options include accessing UN peacekeeping funds or setting up a dedicated AU fund for soliciting international donations.

In addition, the United States should create a coordination forum to synchronize all the players currently fighting al-Shabab. The separate efforts being conducted by Britain, Qatar, Turkey, the UAE, and various subnational Somali authorities would be more effective if merged under a single institutionalized framework, much like the U.S.-led “Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS” has achieved. In particular, a joint operations center could help maximize the impact of independent U.S., Emirati, and Turkish air operations in Somalia. The “S6” group of security donors (Britain, the EU, Turkey, the UAE, the UN, and the United States) could serve as the basis for this platform.

Finally, in pursuing all of these efforts, Washington will have to remain mindful of East Africa’s complex geopolitics. For example, Eritrean and Emirati meddling in Sudan could complicate the situation in Somalia.

Ido Levy is an associate fellow with The Washington Institute’s Military and Security Studies Program and a PhD student at American University’s School of International Service.