- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3912

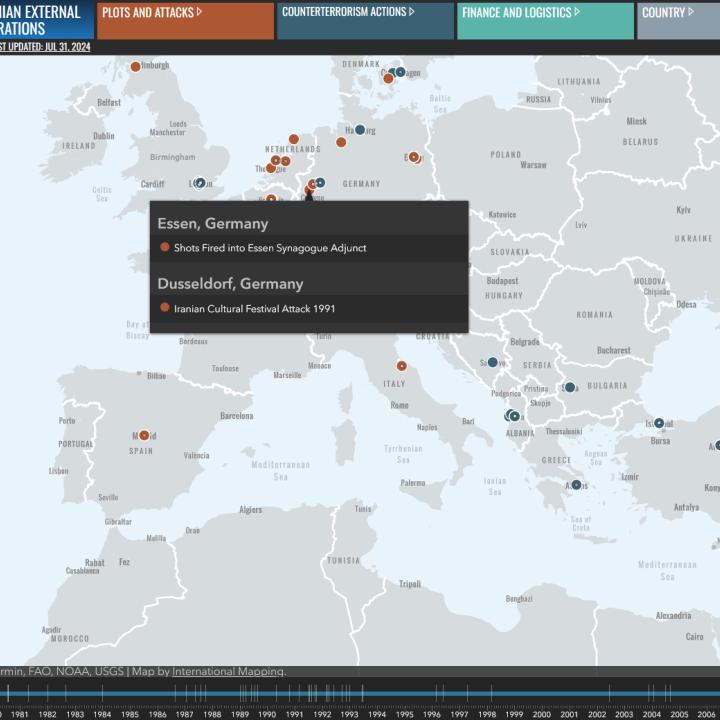

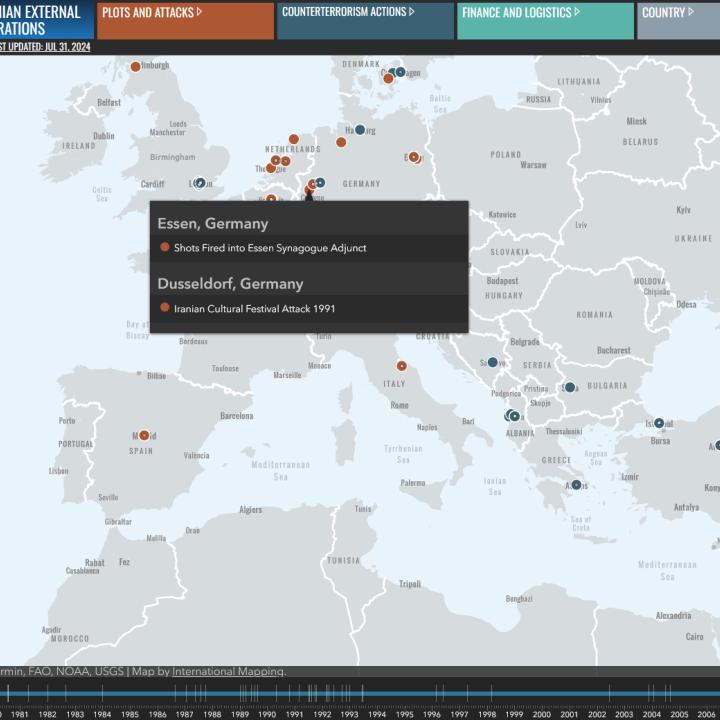

Mapping Iranian External Operations Worldwide

Three counterterrorism experts and former officials discuss a powerful new interactive tool and its implications for mobilizing international pressure on Iran and its proxies.

On August 7, The Washington Institute held a virtual Policy Forum with Matthew Levitt, Magnus Ranstorp, and Norman Roule. Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler Senior Fellow at the Institute, director of its Reinhard Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence, and creator of its just-launched Iranian External Operations Interactive Map and Timeline, a first-of-its-kind multimedia tool for tracking the regime’s activities abroad. Ranstorp is a strategic advisor at the Swedish Defence University’s Centre for Societal Security and former special advisor to the EU Radicalisation Awareness Network. Roule is a nonresident senior advisor at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and a former CIA official whose roles included national intelligence manager for Iran. The following is a rapporteur’s summary of their remarks.

Matthew Levitt

Iran has been carrying out external operations since the early days of the Islamic Revolution, but they have increased in recent years and focused on more sensitive targets, as underscored by the recent arrest of a Pakistani agent of Iran for plotting attacks in the United States.

The Iranian External Operations Map is the largest database of open-source information about the regime’s illicit activities to date, searchable by category, location, timeline, and keywords. It includes around 400 entries at launch, with more to come, each supplemented by photographs, videos, incident summaries, geographical/thematic linkages, and primary-source documents.

Iranian diplomat Assadollah Assadi’s arrest in September 2018 was a watershed moment, leading the European Union to designate different units of Iran’s Intelligence Ministry and capturing the attention of American officials. This evoked questions as to what Assadi’s plot meant, including whether it represented an escalation. These questions prompted the creation of an open-source dataset tracking Iranian external operations since the Islamic Republic’s establishment in 1979.

The map has a user-friendly interface that draws on this dataset. It tracks several main types of plots: targeted assassinations, indiscriminate attacks, abductions, intimidation, and surveillance to support such operations. It primarily focuses on the who, what, where, when, and why of attacks. For example, who are the perpetrators of such plots (Iranians, criminals, proxies) and targets (Iranian dissidents, Americans, Israelis, Jews)? While the data relies on open-source information, extensive due diligence went into verifying the credibility of each report, including with law enforcement, intelligence members, and policymakers.

In recent years, Iran has significantly ratcheted up its external operations, especially targeting Iranian dissidents and journalists. These attacks are a tool Tehran has consistently used since 1979, excluding a break after the September 11 attacks. Iranian intelligence agents, personnel from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force (IRGC-QF), and diplomats are the primary perpetrators of these external operations. For assassinations, the regime is increasingly relying on criminals and criminal organizations, as demonstrated by the recent indictment of Asif Merchant for attempting to hire criminals to assassinate former president Donald Trump. Indeed, assassinations are the most common type of attack, followed by indiscriminate attacks, abductions, surveillance operations, and cyberattacks. These categories are not mutually exclusive; there are cases that overlap. These operations largely occur in Europe and the United States, highlighting that Tehran is not deterred from carrying out operations in logistically difficult locations or where the consequences might be greatest.

Iran is likely to keep conducting attacks because there are no severe consequences or tools in place to deter it. Again, this includes plots in locations where the threat to the regime is greatest. Kinetic responses have not been widely used against Iran for fear of retaliation, but there are multiple tools that can be used to deter the regime, such as designating the IRGC at the UN and enforcing stricter sanctions to demonstrate that these plots are illegal and unacceptable.

The map’s introductory essay and tutorial provide further detail on how to access and collate these and other data points. As a “living” project, the digital interface will be updated as more information and documentation become available. Users are encouraged to submit specific or general feedback and documents using the mail widget. All such information will be carefully vetted before inclusion in the database.

Magnus Ranstorp

The map is a fantastic resource for seeing an aerial view of Iranian proxy warfare, which has been constant since the Islamic Republic was founded and fifty-three U.S. diplomats and citizens were taken hostage. The basic idea was to export the revolution and fight enemies abroad, with Hezbollah the prime organization working in synchronicity with the IRGC-QF and Iranian intelligence.

The map provides an excellent view of both old and new plots, including the 1992 and 1994 bombings in Buenos Aires. In a recent 711-page ruling, Argentina’s Supreme Court showed that Iran was responsible for those attacks. Flash forward to 2023, and the head of Mossad was saying even before the October 7 attack that the agency had foiled twenty-seven plots against Jews and Israelis abroad.

A few instances in the database are illustrative of what Iranian intelligence is doing. In 2018, the leader of the Arab Struggle Movement for the Liberation of Ahwaz (ASMLA) was being surveilled in preparation for an assassination by an individual selling intelligence to Iran. Similarly, a Swedish national who was part of ASMLA was kidnapped in Turkey and taken to Tehran. Most significant in recent years was the IRGC’s deployment of a married couple to Sweden to surveil Jewish targets. Because Swedish hostages were being held in Iran on false pretenses, Stockholm was unable to respond harshly to these plots.

Indeed, Sweden is a frequent target for Iranian operations. Israel’s embassy in Stockholm is often under immense pressure, with incidents that have included a bomb left in its driveway and a shooting. Iran is also increasingly using Swedish organized crime groups—primarily the Foxtrot network—to attack Israeli targets across Europe.

The database also shows that using outside operatives from the “axis of resistance” is part of Iran’s broader repertoire, making it essential to target the regime’s support for proxy groups. Israel has targeted the IRGC-QF and others in Syria, but the EU could do more. Iran will use any group it can and pressure whoever it has a relationship with to carry out attacks against Israeli embassies.

The practice of abducting foreign citizens and diplomats also needs to be forcefully condemned. Despite Tehran’s involvement in taking 103 Westerners hostage in the 1980s, it never paid a price. To achieve deterrence, the United States and EU must be tougher with Iran on this and other issues.

Norman Roule

Matt and his team should be congratulated for creating a tool that the international community can use to better understand the threat from Iran. Four main themes emerge from this powerful, user-friendly map.

First, the project as a whole shows that Iran’s plots represent industrial-scale global activity. The level of targeting, recruiting, technology, and surveilling make clear that these plots are not the actions of a rogue faction within the country’s intelligence agencies or IRGC-QF, but a tool of power projection and lethal statecraft.

Second, the timeframe should be of concern. These operations were seemingly developed at times when Iran had the greatest opportunity for diplomatic engagement and normalization, and in places where governments showed a willingness to overlook its transgressions. Unfortunately, this shows that engagement with Tehran does not result in reduced aggression.

Third, it is important to acknowledge the personnel being used in these plots, such as Iranian officials, third-party actors, and criminals. Instead of treating this as a state issue, the international community treats it as a legal issue. The response to Iran tends to be shallow and symbolic.

Fourth, Iran’s tactics point to the need for clearer, more consistent international red lines. The weapons involved in its plots are often mass-casualty weapons such as explosives, but again, the response is rarely if ever commensurate.

The first question raised by the dataset is: why does Iran engage in these operations? The answer is that it pays no serious price for doing so. International responses are typically limited to public statements, and Russia and China have successfully blocked action at the UN. Unless the regime believes that the price for these actions will threaten its hold on power, it will see no reason to halt them.

The second question is: what can be done to combat these plots? This is a global problem, so a multilateral approach is necessary—not only economic and diplomatic pressure, but also efforts to target the leadership in Iran that is managing this enterprise. To this end, an international effort is needed to eradicate the IRGC-QF, a designated terrorist group. There is also a need for military action against Iran itself. Authorities need to consider conducting surgical, precise military action against the leaders of plots, not just trying to foil the plots.

U.S. and European officials know how to combat Iran, but there are challenges and tradeoffs to dealing with such a regime. For example, if officials want Tehran to cooperate on nuclear matters, they need to understand that the regime will take whatever money it receives as part of that process and spend it on additional external operations and regional proxies. Accordingly, any actions against Iran need to be multilateral and long term.

This summary was prepared by Sarah Boches. The Policy Forum series is made possible through the generosity of the Florence and Robert Kaufman Family.