- Policy Analysis

- Interviews & Presentations

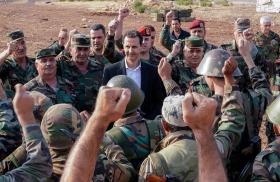

Middle East Matters: Back to Normal? The Region Reaches Out to Assad

Part of a series: Middle East Matters

or see Part 1: Middle East Matters, Episode One: The Murder of Lokman Slim: Justice Delayed in Lebanon

Two experts discuss why Arab governments are increasingly normalizing with the Syrian regime and what consequences this may hold for U.S. policy.

On April 24, Andrew Tabler and Ahed al-Hendi appeared on episode 3 of The Washington Institute video series Middle East Matters, hosted by Institute fellow Hanin Ghaddar. Tabler is the Institute’s Martin J. Gross Senior Fellow and former senior advisor to the special envoy for Syria engagement at the State Department. Al-Hendi is an independent Syria analyst. The following is a rapporteur’s summary of their remarks. Watch the full episode.

Andrew Tabler

Regional efforts to engage with Syrian president Bashar al-Assad are not new. There was Amman and Cairo’s effort to move gas and electricity from Jordan to Lebanon with Assad taking a stake. That plan has not gone anywhere. The Jordanians also opened the Jaber Crossing into Syria—and the kingdom was soon flooded with Captagon produced inside Syria. These outcomes are certainly not what Jordan or any of the other Arab countries wanted, and now they are suffering from their decisions.

Another track has been led by the United Arab Emirates. Beginning in 2018, the UAE sought to provide monetary inducements to Assad in return for undermining Turkey and Qatar; later, it argued that such inducements might help get Iran out of Syria.

Arab governments believed that engagement with Assad was possible in part because the Biden administration has not made Syria a priority. The February earthquakes in Turkey and Syria further emboldened them to pursue fuller normalization. Yet engaging Assad has a horrendous track record, so it remains unclear why Arab states are still pursuing it and what they are demanding from Damascus. What is on the table, exactly? Because U.S. sanctions are not going away.

The Arab League is often a good indicator of regional unity on particular issues. Readmitting Syria to the league would require just a simple majority vote, but supporters of normalization want a unanimous vote instead. In their view, any dissenting votes would render the decision meaningless; they also believe a unanimous vote would show the world that a different path is needed on Syria.

Regarding U.S. sanctions, the restrictions stemming from the Caesar Act will sunset in 2024, so they would need to be reintroduced in Congress to remain in effect. Given the current mood on Capitol Hill, a renewal is all but assured. Yet Arab officials may believe they can change these U.S. sentiments before 2024.

Normalization efforts also have implications for the U.S. military presence in Syria. American troops are legally deployed there under an Article 51 self-defense request from the Iraqi government, allowing them to stay as part of the fight against the Islamic State. Yet Russia, Iran, and Damascus want U.S. troops to leave. And if Iraq and the rest of the Arab League decide to officially normalize relations with Assad, the regional pressure against the American presence could increase significantly in the not too distant future. Among other things, this outcome could compel the U.S.-allied Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to strike a deal with Assad, essentially giving a major swath of territory back to the regime—at least legally. It would also likely give new life to the Islamic State, since none of the conditions that led to the group’s declared jihad in Syria (or the domestic popular uprising, for that matter) have changed.

Ahed al-Hendi

Assad’s illicit Captagon trade is generating up to $5 billion for the regime. Over the past decade, he has lost control of almost all of Syria’s natural resources, including oil fields, water supplies, and agricultural production. Most of the revenue that used to come from manufacturing does not exist anymore either—it has been destroyed or moved out of the country. His solution was to turn Syria into a Captagon powerhouse responsible for trafficking the drug to many other Arab countries, and this flow will continue unless the regime finds another way to generate money. The U.S. Congress has made clear that the Caesar Act sanctions will remain in place, making it difficult for the regime to receive money from Arab countries. Hence, it is wishful thinking to believe Assad will stop a trade that is providing him with cash he cannot otherwise obtain.

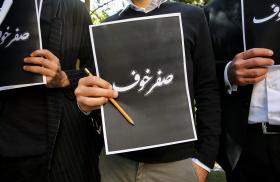

The regional effort to normalize with Assad in the hope of stopping his activities is not new. The same effort was tried in the past when he used to export terrorism by supporting extremist groups in Arab countries. Normalization did not succeed then, so it is unlikely to succeed now.

Although most sanctions are still in effect, the decision to allow humanitarian and earthquake relief might give some leeway for Arab countries to send Assad money. Moreover, the Saudis seem bent on directly engaging with the regime. They are doing the same in Yemen—in the past, Riyadh tried to assassinate top Houthi leaders, but now it is shaking hands with them. These developments are due to American disengagement from the region, which has left many Arab countries to deal with their problems on their own—in Saudi Arabia’s case, through a rapprochement policy.

Ultimately, however, proposals such as readmitting Syria into the Arab League and providing Hajj licenses are just symbolic gestures. In the latter case, for example, many Syrian citizens and refugees who live abroad already use foreign passports, making Hajj licenses useless. True, such gestures help Assad boost morale among his core supporters, many of whom are struggling because of economic problems and living under the poverty line. In that sense, the normalization process is giving Assad a free card, which in turn feeds his narrative. Yet none of these symbolic gestures will have an impact on the ground in the long term, let alone bring back Syria to its pre-2011 days.

This summary was prepared by May Kadow and Erik Yavorsky.