- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 2746

More Information Is Needed to Evaluate Implementation of the Iran Nuclear Deal

Experts need sufficient information to make informed judgments about whether the deal's terms are being implemented in full, and it is unclear whether any mechanism exists to detect procurement violations.

On January 10, officials from Iran and the P5+1 countries met in Vienna under the auspices of the Joint Commission, a body established by the 2015 nuclear deal and coordinated by Frederica Mogherini, the European Union's high representative for foreign affairs and security policy. Numerous media reports indicate that the commission was set to approve Tehran's request to import 130 tons of natural uranium from Russia and possibly more from Kazakhstan. Yet Iran has no civil need for that uranium -- it already possesses ample supplies for its research reactors, and Russia was previously contracted to provide sufficient fuel for the nuclear power plant at Bushehr.

Aside from concerns about the implications of these potential uranium imports, the reported decision highlights a deeper, ongoing issue with implementation of the nuclear deal -- thus far, information about what the Joint Commission allows Iran to do has come largely from news leaks. Outside experts have not been able to make informed opinions about how well the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) is working because they lack sufficient information from the Joint Commission and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The scheduled January 18 UN Security Council (UNSC) discussion of Resolution 2231, which embodies the JCPOA as well as the ban on Iranian arms exports, is a good opportunity to provide greater transparency that allows for better-informed judgments about the deal.

DOCUMENTING CONCESSIONS TO IRAN

The Joint Commission is assigned sixteen tasks, mostly to "review and approve" Iran's plans on seven issues (as well as to "assess and then approve" and "review and decide" on two other issues). It is also intended "to consult and provide guidance on other implementation matters that may arise."

According to the terms of the nuclear deal, "The work of the Joint Commission is confidential and may be shared only among JCPOA participants and observers as appropriate, unless the Joint Commission decides otherwise." In practice, the members of the Joint Commission appear to have announced the dates of quarterly meetings but nothing about what was discussed or decided. On December 23, the IAEA released eight Joint Commission documents that Mogherini had approved for distribution -- the only commission decisions ever publicly released. All of these documents predate Implementation Day of the nuclear deal, which fell on January 16, 2016 (though one document about procurement was updated in September).

Four of the documents spell out how the P5+1 countries (Britain, China, France, Russia, the United States, and Germany) approved concessions to Iran that went beyond what was provided for in the JCPOA: namely, on hot cells, on fuel plates and low-enriched uranium for the Tehran Research Reactor, and on heavy water in excess of the limits set in the nuclear deal. News of these concessions leaked several months ago, and JCPOA critics viewed both the concessions and the secretive manner in which they were made as confirmation of their skepticism about the deal. One could argue that these concessions were minor and justifiable, but that raises an obvious question: why were they not included in the publicly released text of the original JCPOA? Putting them in undisclosed documents makes them look suspicious, even if they are not.

Informed observers note that the Joint Commission has made many other decisions in addition to those released in December, in line with its obligation to review and approve Iran's plans on numerous issues. Each of those decisions either held Iran strictly to the JCPOA's terms or granted it concessions far beyond what was agreed to in the nuclear negotiations -- the actual outcomes are unknown. Absent information about those decisions, observers cannot make informed judgments about whether the nuclear deal is working as intended or has become a minor speed bump on Iran's road to a disturbingly robust nuclear program.

AN EMPTY FACADE OF A PROCUREMENT CHANNEL?

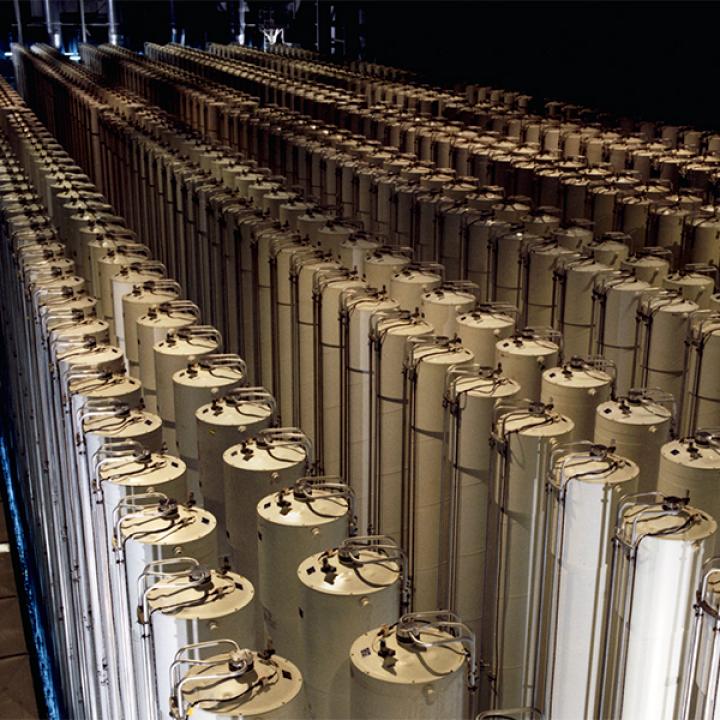

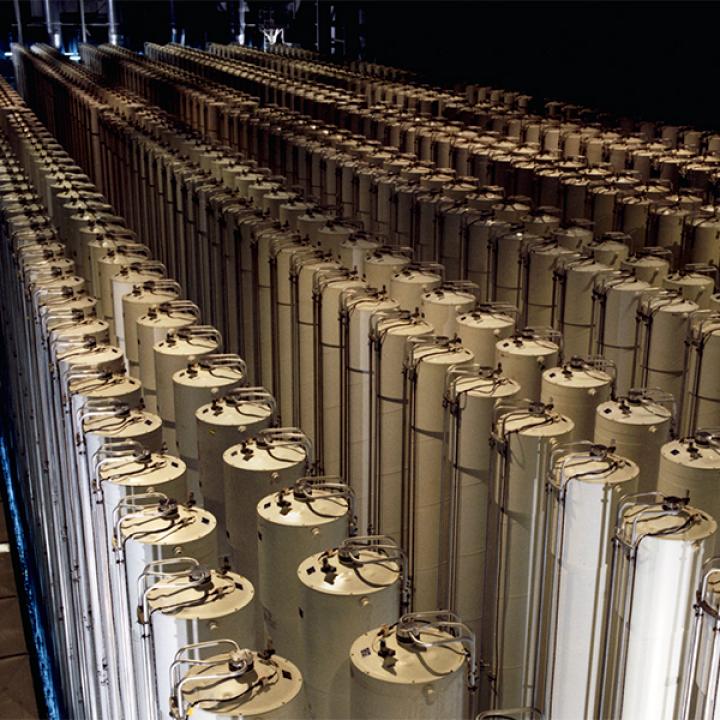

The bulk of the documents released December 23 are about the procurement channel, the JCPOA mechanism intended to approve and monitor all international transfers of items, materials, equipment, goods, and technology required for Iran's nuclear activities, with exceptions for certain JCPOA-mandated activities such as conversion of the Arak reactor. Taking these documents together with the July six-month report by the UNSC-appointed facilitator for implementation of Resolution 2231, it could be argued that the manner in which the procurement channel has been set up provides no effective restrictions on Iran. The July report stated that only one application to the channel had been made in the half year since Implementation Day, and that it was subsequently withdrawn. The main "progress" noted by the facilitator was that the UNSCR 2231 website had been set up.

Before leaving office December 31, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon issued a second report about UNSCR 2231 that is due to be released when the Security Council discusses it on January 18. A leaked passage from that document states, "I have not received any report on the supply, sale, transfer, or export to the Islamic Republic of Iran of nuclear-related items undertaken contrary to the [resolution]." Yet that statement is difficult to evaluate because there is little public information about what, if anything, has been done to detect violations or enforce the procurement channel. Private communications indicate that the Procurement Working Group (PWG) set up by the JCPOA met thirteen times in 2016, but details on those meetings are unavailable.

It will be interesting to see what else the secretary's new report says about compliance with the procurement channel. States are responsible for ensuring such compliance, but it is not clear whether there has been any outreach to relevant industries and firms to educate them about the channel's requirements. It is not even clear if the facilitator has developed a list of the firms that previously supplied nuclear-related items to Iran. And there does not appear to be any mechanism for input about procurement from outside technical experts -- the previous UN panel of experts on Iranian nuclear restrictions was disbanded when the JCPOA was implemented.

Also disbanded on Implementation Day was the monitoring committee to which member states could report violations. Indeed, there may not be any mechanism to respond to reports of Iranian procurements made outside the official channel. If another country learns of such a procurement, does the PWG have the authority to order the state to block the sale? And if the materials in question have already been sent to Iran, is there a procedure for ordering their return? There is also no apparent mechanism to track applications denied by countries with robust export-control regimes, much less to share information about such denials with countries that have fewer resources or less political will to investigate Iranian procurement requests closely. It will be interesting to see if the new report touches on any of these matters, which have not been discussed in previously released documents.

Currently, applications made to the PWG require that states confirm their right to conduct end-use verification, mainly so that any dual-use items Iran declares to be for non-nuclear purposes are not diverted to the nuclear program. Yet states have no obligation to tell the PWG how they intend to verify end-use, nor are they required to regularly inform the group about what verification they have conducted and what the results were.

Similarly, if the IAEA detects the procurement of certain proliferation-sensitive goods outside the channel, the agency may not be permitted to disclose such discoveries due to its own confidentiality agreements with Iran. Furthermore, some dual-use items covered by the procurement channel fall outside the IAEA's purview, so the agency would likely be unable to identify their (mis)use.

FACILITATING A MORE INFORMED EVALUATION

It is impossible to make informed judgments about how the nuclear deal is working unless sufficient information is made available. When important information emerges only through leaks, and when those leaks show that Iran is gaining concessions not in the JCPOA text, the result is to reinforce suspicions about the deal and undercut claims that it is working well.

The lack of transparency has been exacerbated by the drop-off in information from the IAEA post-implementation. The agency no longer provides data on the amount of enriched uranium Iran produces each month, its current low-enriched uranium inventory, the amount of uranium ore concentrate (yellowcake) produced from its mines, or its existing uranium hexafluoride stocks. Nor does the agency report on the frequency of short-notice inspections, if any are actually being conducted.

The JCPOA specifies that "decisions by the Joint Commission are to be made by consensus," so Washington would be entirely justified and appropriate in stating that it will block future decisions unless the commission institutes greater transparency about the JCPOA's implementation. This means more information from the IAEA, more information about the procurement channel, more effort to inform potential suppliers about the channel, a clear way to report suspected violations of procurement restrictions, more information required from states about their end-use verification efforts, and more information about the Joint Commission's deliberations. All of these are issues fall well within the commission's responsibility "to consult and provide guidance on other implementation matters that may arise," in the words of the JCPOA.

Katherine Bauer is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute and a former Treasury Department official. Patrick Clawson is the Institute's Morningstar Senior Fellow and director of research.