Part of a series: Oslo at 30

or see Part 1: Oslo at 30: Personal Perspectives from Washington Institute Scholars A Compendium

A panel of former Israeli, Palestinian, and U.S. officials discuss the legacy and future of the Oslo Accords as a framework for achieving Israeli-Palestinian peace.

On September 11, The Washington Institute held a virtual Policy Forum with Neomi Neumann, Ghaith al-Omari, Dennis Ross, and David Makovsky. Neumann is a visiting fellow at the Institute and former head of the Israel Security Agency’s research unit. Omari is a senior fellow at the Institute and former member of the Palestinian Authority negotiating team. Ross is the Institute’s William Davidson Distinguished Fellow and former U.S. point man on the peace process during the Bush and Clinton administrations. Makovsky is the Institute’s Ziegler Distinguished Fellow and former senior advisor to the State Department’s special envoy for Israeli-Palestinian negotiations. The following is a rapporteur’s summary of their remarks.

Neomi Neumann

Despite predictions to the contrary, the PA is still functioning as an authority and address that provides civil services to its people. Yet it is structurally weak, economically unstable, and corrupt. The resultant decrease in the PA’s legitimacy has eroded public trust in the very idea of a two-state solution with Israel.

While the political horizon has dimmed, a second chapter of Oslo is still possible. Three critical elements must coalesce to revive the peace process. First, both sides need brave leadership to break through the diplomatic deadlock. Second, both publics must legitimize their political leadership to validate each government’s decisionmaking. Lastly, voices that oppose peace must become weaker or irrelevant in the political conversation.

Yet President Mahmoud Abbas has failed to leave a real legacy (i.e., a Palestinian state dedicated to nonviolence), while Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu did his part to advance a “manage the conflict” policy instead of ending the conflict. In this climate, rejectionist voices have gained relevance and radical views now dominate key aspects of decisionmaking. For a peace process to rematerialize, some changes in both leaderships will be necessary.

Resuming political dialogue will also require a smooth leadership transition once Abbas exits the arena. Until then, it is in Israel’s strategic interest to strengthen the PA; otherwise, a vacuum could emerge post-Abbas, enabling figures who support violence to take center stage. Rehabilitating the PA will require substantial Israeli and Palestinian steps—not just real reforms, but also measures that preserve the possibility of dialogue and the wider political horizon. Israel will need to halt West Bank settlement expansion and increase security cooperation with the PA in a manner that curbs terrorist acts by extremists on both sides. Although restoring the PA’s legitimacy and effectiveness will not be easy, doing so is essential to the future of the peace process.

Substantial progress in the political arena is unlikely in the near future, but it is incorrect to say that Oslo is irrelevant. The accords created a reality that is impossible to reverse, and all parties should do what they can to sustain the belief that Oslo’s next chapter will be written soon.

Ghaith al-Omari

Historical reflection on the post-Oslo years can sometimes lead observers to construct an idyllic pre-Oslo past. Yet both parties need to bear in mind the actual status quo when the accords were signed.

In 1993, the Palestinian national movement was at one of its weakest moments, and the Palestine Liberation Organization found itself isolated after siding with Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. With no diplomatic or financial resources to draw on, the PLO was deeply constrained, and Oslo essentially saved the Palestinian cause as an organized national movement.

Oslo also laid the foundation for two crucial structures that are still with us today: the PA and the two-state solution. Although the PA is currently mired in internal issues, it has created an address for the movement to exercise its political aspirations and an institutional framework for the realization of a Palestinian state. Moreover, the two-state idea would not exist in the first place if Oslo had not realized the possibility of mutual recognition. Achieving a viable two-state solution is still far away, but the concept of “two states for two peoples” has become a matter of diplomatic consensus and the preferred framework through which the international community approaches the conflict.

Even so, Oslo’s foundations are under extreme duress. The PA has yet to meet its initial purpose—to create a Palestinian state—and public confidence in a two-state solution is waning. To move forward, the parties should focus on four core policies:

- Do no harm. In Israel’s case, this means halting the unchecked settlement expansion that is largely designed to collapse Oslo’s two-state paradigm.

- Rehabilitate the PA, since its collapse would render the two-state solution obsolete. Currently, the PA is the only available Palestinian address for realizing a state, since Hamas is tainted by terrorism and lacks the international legitimacy to further the cause.

- Leaders on both sides should do more to inspire cooperation among the younger generations, who have been demoralized by decades of dysfunction.

- Pursue regional integration in a manner that improves the lives of Palestinians and creates the framework for greater Arab-Palestinian engagement. For instance, an Israel-Saudi deal could be a vehicle for revived economic support in the West Bank.

Dennis Ross

One critical lesson of the Oslo Accords is that the two sides had very different expectations about what the declaration of principles represented, and this gap contributed to future tensions. Many Palestinians perceived Oslo as giving birth to a state-in-waiting that would end the occupation and facilitate independence. In Israel, Oslo was largely viewed as a gradual devolution of authority to the PA in order to minimize security concerns. Thus, while both leaders showed enormous creativity in overcoming some of their differing expectations during the first two years of talks, the process largely failed to meet either people’s hopes. This created an opening for extremists on both sides to subvert the process and discredit moderates.

Prior to Oslo, decades of mutual rejection and two peoples fighting for the same land had rendered the Israeli-Palestinian conflict intractable. Oslo represented an end to the conflict’s existential nature by replacing the legacy of mutual rejection with mutual recognition. It also created an address for the Palestinian movement.

Today, however, the PA’s eroding credibility is perilous to diplomacy, and violence is beginning to take on a life of its own amid complete paralysis between the two governments. If no change or sense of possibility emerges before Abbas leaves the stage, many Palestinians will remember his preference for nonviolence as a failure and increasingly favor those who claim that violence is necessary and negotiations lead nowhere. Such conditions would only hasten the drift toward a one-state outcome, which is a prescription for enduring conflict.

Although current Israeli-Palestinian leadership dynamics would seem to make any change in the current trajectory impossible, an Israeli-Saudi deal could change that. The Saudis want to achieve something meaningful for the Palestinians—something that changes their lives in practical terms such as their daily movements, economic well-being, and diplomatic horizon. More specifically, this would require Palestinian economic access in Area C of the West Bank, limitations on the territorial expansion of Israeli settlements, and, perhaps, greater territorial responsibility for the PA. Yet without genuine PA reform on governance issues and corruption, foreign donors will not invest in infrastructure, and the Palestinian security services will be unable to substantially improve their performance—a sine qua non for any transfer of “C Areas” to “B areas.” Bottom line: while an Israeli-Saudi deal is still only a possibility, it has the potential to preserve the peace process and beneficially transform the geopolitics of the Middle East and beyond.

David Makovsky

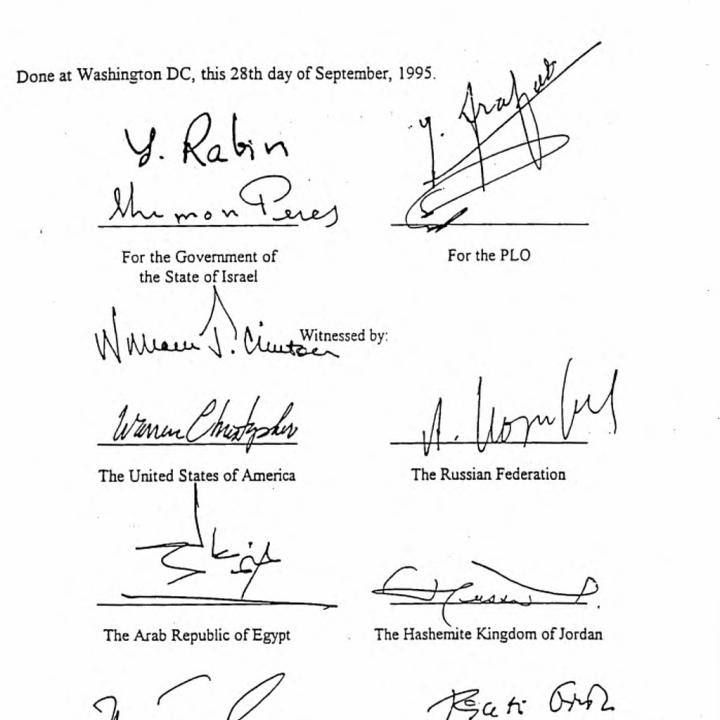

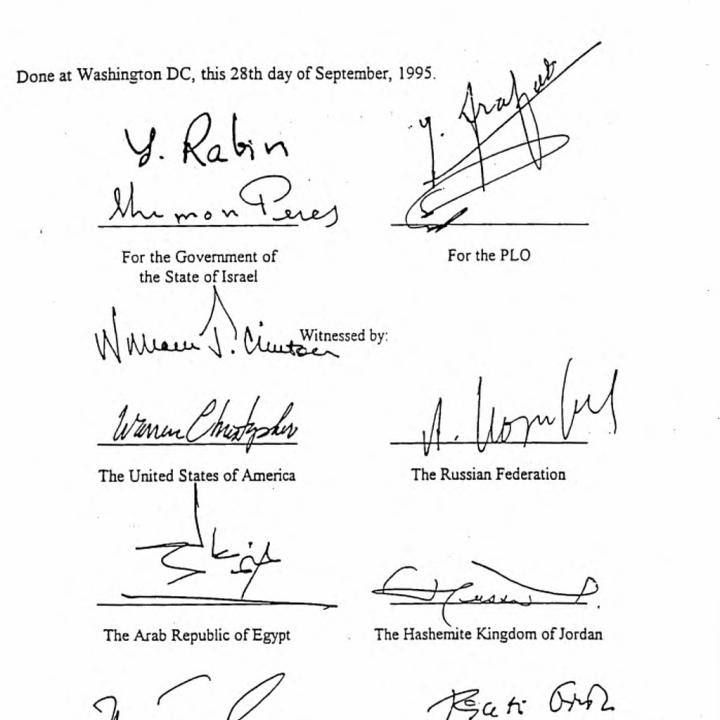

Oslo fundamentally changed the conflict’s trajectory. The two parties had not dealt directly with each other prior to Oslo, and Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin seized the moment to usher in a new chapter of Israel’s history. Newly declassified documents from a 1993 cabinet meeting highlight his strategic thinking on the eve of Oslo and his belief that the process would be a devolution of powers based on proven Palestinian security performance. (Note: An expanded version of Makovsky’s forum remarks and related insights was published in PolicyWatch 3783.)

This summary was prepared by Sydney Hilbush. The Policy Forum series is made possible through the generosity of the Florence and Robert Kaufman Family.