Part of a series: Transition Notes 2025

Rather than choosing between diplomacy and military action, the Trump administration should think of these options as mutually supportive, sequencing its actions in hopes of achieving the best and least costly outcome.

In the first in a series of TRANSITION 2025 memos, Michael Singh discusses how the Trump administration can take on a regime facing historic struggles but edging perilously toward the bomb.

Executive Summary

The Iran that confronts President Trump in January 2025 will be more vulnerable than at any time since 1979, but also closer than ever to possessing a nuclear weapon. At the same time, Israel may be on the verge of conducting military strikes against Iran’s nuclear program. Working closely with Israel, other regional partners, and the so-called E3 (France, Germany, and the UK), the Trump administration should use the window of opportunity before the JCPOA’s “snapback” provision expires in late 2025 to coordinate military, economic, and diplomatic pressure against Iran with the goal of securing a comprehensive set of diplomatic agreements superior to the 2015 nuclear deal. The administration should simultaneously prepare for military strikes should that diplomacy fail.

***

As he steps back into the Oval Office, President Donald Trump confronts a paradoxical Iran. The Iranian regime has never been weaker, thanks to its lack of legitimacy at home and the decimation of its regional proxies and partners like Hamas, Lebanese Hezbollah, and former Syrian president Bashar al-Assad. Yet Iran has also never been closer to possessing a nuclear weapon, and halting Iranian nuclear advances has never been more urgent. Indeed, these two phenomena seemingly reinforce each other: as the Iranian regime gets weaker in conventional terms, the allure of acquiring nuclear weapons grows.

The Iranian regime bears responsibility for the Hamas-led attack against Israel on October 7, 2023, and for the regional chaos that followed. Whatever the regime’s role in the actual planning of that attack, it would not have been possible absent the arms, training, and funding Iran provided not just to Hamas but to Hezbollah, Yemen’s Houthi rebels, Iraqi Shia militias, and other proxies. October 7 and its aftermath demonstrated the sheer recklessness of Iran’s regional strategy of proliferating advanced military weaponry to nonstate actors and thereby increasing both the fragility of regional states and the scope and scale of regional conflict. By empowering and arming the region’s most radical and violent elements, Iran virtually ensured that any conflict would be bloody and widespread, and that nonmilitary means of limiting or ending it, such as diplomacy, would be frustrated.

Initially, Iran’s cynical tactics seemed to pay dividends: anti-Israel sentiment grew regionally and globally, leading not just to the diplomatic isolation of Jerusalem and Washington but to a widening rift between the allies. The conflict derailed hopes of near-term Israel-Saudi normalization, and saw Iranian proxies accomplish unexpected feats—for example, Hamas holding territory in Israel in the days after October 7, or the evacuation of Israeli communities, or the Houthis’ effectively closing a key maritime passage despite the U.S. Navy’s efforts to reopen it.

Iran’s luck turned, however, in no small part because of its own inept decisionmaking. Faced with relentless attacks from Lebanon and Syria, Israeli forces on April 1, 2024, killed a senior general in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Mohammad Reza Zahedi. Departing from its traditional approach of asymmetric and often patient reprisal, Iran on April 13 launched hundreds of drones, cruise missiles, and ballistic missiles at Israel, but the attack was almost completely defeated by a U.S.-led regional coalition. The episode not only demonstrated the yawning gulf between Iran’s conventional capabilities and those of the United States, Israel, and their regional partners, but it also underscored that Iran’s isolation significantly exceeded that of Israel. While Iran acted alone, Israel received the support not only of the United States but of others as well. Iran’s action also established a burdensome precedent; when an Israeli strike killed Hezbollah secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah in September 2024, Iran again launched a missile salvo at Israel. This attack also failed, and prompted an Israeli retaliation that reportedly decimated Iranian air and missile defenses and offensive missile-production capabilities. By the time another Iranian adversary—Hayat Tahrir al-Sham—was rolling up Syria’s Assad regime in December 2024, the Islamic Republic had lost the strength and perhaps the will to defend its most important regional ally, leaving it with only the Houthis and Iraqi Shia militias as viable proxies.

The Iranian regime’s errors were manifold, but two stand out—first, it pursued direct, conventional conflict with far superior adversaries, having perhaps internalized its own propaganda about their weakness and its own strength; second, rather than consolidate its early gains, it sought unsuccessfully to press its advantage, only to see those gains reversed. As a result, Iran stands exposed and vulnerable: its territorial defenses and expeditionary military capability have been severely degraded, and several of its key regional proxies are decimated (Hamas, Hezbollah) or routed entirely (the Assad regime).

Iran’s military weakness is compounded by its weakness at home. Due to increased demand from China and lax enforcement of American sanctions, Iranian oil exports climbed in 2023 to nearly 2 million barrels per day, their highest level since just after the 2018 U.S. withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), as the 2015 Iran nuclear deal was known, and up from a low of 400,000 bpd in 2020. As a result, Iran earned a reported $70 billion in oil revenue in 2023, helping fuel GDP growth of 5 percent that year, according to the IMF. This ostensibly rosy picture, however, obscures the harsh economic realities faced by Iran. The IMF projects that Iran’s economic growth will fall in 2024 and subsequent years, failing to even approach the regime’s target of 8 percent. Iranian president Masoud Pezeshkian has asserted that Iran requires US$200–250 billion in investment to reach its growth target; such investment is likely impossible with U.S. sanctions in place, and Iran instead experienced unprecedented capital flight in 2023. Even Iran’s surge in oil exports comes with a significant catch—exporting the oil and repatriating the revenues are costly and require subterfuge, meaning that Iran effectively sells its oil at a large discount to the market price and that some revenues flow directly to actors such as the IRGC rather than into state coffers. Further, 90 percent of Iran’s oil exports are purchased by China—up from 25 percent in 2017—giving Beijing enormous leverage over Tehran. Perhaps most embarrassing and destabilizing for Iran, however, is its domestic energy crisis. Due to overconsumption, underinvestment, mismanagement, and war, Iran is experiencing worsening shortages of natural gas and electricity that have significantly hampered daily life in the country.

Iran’s energy crisis risks exacerbating the regime’s already dire crisis of political legitimacy, vividly illustrated by the 2022–23 “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests, followed by anemic participation in the country’s 2024 parliamentary election and the special presidential election after the death of Ebrahim Raisi. Even according to official statistics, the March 2024 parliamentary election saw just 41 percent voter turnout, the lowest reported figure since Iran’s 1979 revolution. Official turnout for the July presidential election was even lower, at just under 40 percent. Normally, such a sparse showing would indicate a hardliner victory, but in this case the presidency was won by the comparatively moderate (yet regime loyalist) Pezeshkian, a development likely attributable to a combination of factors—popular protest voting, the regime’s desire to put forward a friendlier face to convince both its own population and foreign actors of its interest in change, and a possible perception by Iran’s Supreme Leader that the “ultra-hardliners” represented by former nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili posed a greater threat to his grip on power than the timid Pezeshkian and his coterie.

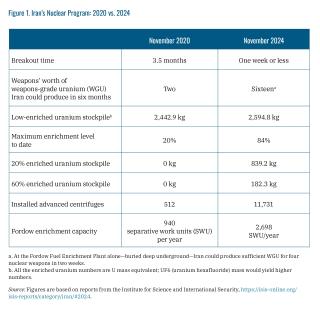

It is surely no coincidence that as its political, economic, and military strength has ebbed, Iran has accelerated the advancement of its nuclear program and decreased its cooperation with international nuclear inspectors, while public discussion about obtaining nuclear weapons has become more frequent and explicit. (See figure 1 for a bleakly instructive comparison of Iran’s nuclear program in November 2020 and November 2024.)

Iran’s technical advances have proceeded in lockstep with reduced cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Among other things, Iran has effectively expelled veteran nuclear inspectors, misstated details in its reports, refused to cooperate fully with the agency’s investigation into sites where undeclared nuclear activities and materials were discovered, and refused to declare or provide required information regarding new nuclear construction. The deficiencies in Iran’s cooperation with the IAEA, combined with its very short breakout times, cast serious doubt on whether inspectors could fully account for Iran’s nuclear materials and activities, and whether they would detect a breakout attempt or even a serious advance short of breakout quickly enough for the United States to preempt it. At this point, Iran could have sufficient weapons-grade enriched uranium for a nuclear weapon in just days, and could produce a usable nuclear weapon in six months or less—a timeline that may not even matter if it can avoid detection or hide its WGU from inspectors and foreign intelligence after producing it.

As Iran’s ability to quickly produce nuclear weapons has advanced, domestic discussion about the possibility of doing so has grown increasingly open and explicit, and Iran has sought to use its nuclear weapons–threshold status as a coercive policy tool. While Tehran has long threatened withdrawal from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) in response to any number of Western policy moves, regime officials have simultaneously maintained that Iran would never actually pursue nuclear weapons because they were forbidden by Islam. Over the past year, however, messaging on this topic has shifted notably. Current and former Iranian nuclear officials have stressed Iran’s capability to build nuclear weapons if it chose to do so. In May 2024, an advisor to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei warned that the regime would change its stance on nuclear weapons if Iran’s “existence were threatened.” Similar statements have been issued by officials of the IRGC—the organization likely responsible for building and fielding nuclear weapons if Iran followed this path—and Iranian foreign minister Abbas Araqchi, who warned in November 2024 that the window for diplomacy was narrow and that Iran was prepared for “any scenario.”

For its part, Israel—emboldened by its successes against Iran and its proxies, as well as the Iranian regime’s multiplying weaknesses—is in the midst of a debate over whether to conduct military strikes against Iran’s nuclear program. The arguments for such a step range from restrained (i.e., that the opportunity and need will never be better) to ambitious (i.e., that the regime will collapse if targeted). Israeli strikes are certain to draw in U.S. forces, with the lone question being the extent of such involvement. In the most optimistic scenario, Israel would require only certain military articles to conduct a successful strike along with U.S. assistance in defending against an Iranian response, which the Biden administration provided in April and October 2024 as well as on other occasions. However, it cannot be ruled out that the United States would find itself defending American and partner interests in the Gulf against Iranian attack, setting off a military exchange of uncertain direction or duration.

This is the situation that confronts Donald Trump as he begins his second term as president—an Iran arguably more vulnerable than at any time since its 1979 revolution, yet closer than ever to nuclear weapons and openly musing about building them; and an Israeli ally closer than ever to striking Iran, which will inevitably require military support from the United States.

U.S. Policy Under President Biden

When President Biden entered office in January 2021, Iran was one of the few foreign policy issues on which he himself had articulated a clear policy. Among other steps, Biden indicated that the United States would “push back against Iran’s destabilizing activities.” He also pledged to rejoin the JCPOA as a first step toward “strengthen[ing] and extend[ing] the deal’s provisions,” an important recognition that the 2015 nuclear deal was not sufficient to address U.S. concerns. Unfortunately for the Biden administration, the Iranian regime had decided the 2015 accord was insufficient to address its own concerns. Tehran rebuffed U.S. offers to rejoin the JCPOA, insisting instead that what it perceived as the deal’s shortcomings should be addressed, and that the United States should offer restitution for its earlier withdrawal.

That Iran resisted the American effort to revive the JCPOA as written should have come as no surprise. Both sides’ views about the merits of the agreement had evolved since 2015. But whereas the United States was prepared to rejoin the original deal as a good faith first step before addressing its flaws, Iran wanted additional concessions up front to address what it saw as the agreement’s weaknesses. Precisely what Iran might have accepted is unknowable, but the regime seems to have concluded that (1) firmer guarantees against another American withdrawal were warranted; (2) the original deal’s sanctions relief was insufficiently comprehensive; and (3) the United States should provide compensation for the 2018–21 interval during which sanctions relief was not provided. Iran may have felt it had the leverage to pry these concessions from the United States—its nuclear program was more advanced in 2021 than before the signing of the JCPOA, meaning it would have to give up more to comply with the deal’s provisions. What’s more, Iran’s relationship with Russia and China had deepened in the meantime, and regime officials clearly felt that this provided Iran with greater protection from the effects of sanctions.

For its part, the United States not only wanted Iran to give up the additional nuclear advancements it had made in violation of the JCPOA, it also wanted a commitment from Tehran to engage in follow-on negotiations. At the same time, the Biden administration could not credibly provide the additional concessions Iran sought. Compensation for lost revenues was never a possibility, and even if Congress had agreed to broader sanctions relief—a highly unlikely prospect—the administration had no way of compelling future administrations to respect a renewed deal. Indeed, offering Iran additional concessions or payments would likely guarantee withdrawal by a future administration, especially a Republican one.

The Biden administration might have had greater success reviving the JCPOA had it been willing to employ increased pressure along with diplomacy, but it declined to do so, likely in the view that such tactics would make agreement less likely—a view contradicted by historical evidence. Even the second objective President Biden himself articulated as a presidential candidate—countering Iran’s destabilizing regional activities—largely fell by the wayside as the nuclear negotiations became his administration’s near-exclusive focus with respect to Iran. Important work was being done by the U.S. Department of Defense to strengthen military relations with regional partners, but little action was taken to challenge Iran itself. Even when it became clear that the JCPOA revival had failed, the United States shifted to a placeholder policy of “de-escalation for de-escalation.” America refrained from challenging Iran in the region or tightening sanctions, and in exchange the regime made nuclear gestures—such as down-blending a portion of its 60 percent–enriched uranium stockpile—with little actual nonproliferation significance.

This period also witnessed a growing divergence between the United States and its primary partners in the nuclear negotiations, the so-called E3 grouping of the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. The E3 grew increasingly impatient with Washington’s abjuration of pressure and tendency to prioritize opaque bilateral understandings with Tehran, even as it became more alarmed with Iran’s accelerating nuclear advances and increasing defiance of the IAEA. At the same time, the E3 and other European states sought to deter or punish Iran for its mounting military support for Russia’s war in Ukraine, including its provision of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to Moscow beginning in August 2022 (and subsequent construction of a drone production facility in Russia in summer 2023) and of short-range missiles beginning in autumn 2024. The U.S.-E3 divergence was most evident at meetings of the IAEA Board of Governors, where on several occasions the E3 pressed for harsher censure of Iran than the United States preferred, with Washington in one case even reportedly lobbying Board member states against an E3-sponsored measure.

The de-escalation policy was in any event rendered moot by the October 7, 2023, massacre and ensuing regional conflict. U.S. policy toward Iran since then has largely been reactive, focused on seeking to limit Iranian confrontation with Israel.

The Way Forward for the Trump Administration

Iran’s unprecedented vulnerability and the advanced state of its nuclear efforts have fueled a notion in the United States, Israel, and elsewhere that there is both the need and opportunity to act decisively to curtail the threats posed by the Iranian regime. Yet there is no consensus regarding what action to take, or even what its objective should be.

Iran’s nuclear pursuits are part and parcel of a broader regime strategy that analysts term “forward defense” but which might more accurately be described as the employment of (mostly) asymmetric tools of power to threaten adversaries, in part by capturing weak regional governments and bending them to Tehran’s will (see here for an Iranian academic’s description of this strategy). For reasons that are in part historical, ideological, and practical, the Iranian regime has eschewed most traditional means of defense and power projection, whether the building of a conventional military or the establishment of cooperative arrangements with partners and allies. Instead, Iran has sought to keep actual and potential adversaries off-balance by creating threats close to their borders—whether Hezbollah in Lebanon, whose fighters threaten Israel; the Houthis in Yemen, who have fought Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates; or Shia militants in Iraq, who have battled the U.S. military and its local partners. By empowering nonstate actors with direct ties to Iran—and in many cases entirely subservient to it—this strategy also flies in the face of the fundamental norm of state sovereignty. For a time prior to October 7, 2023, Iran exercised de facto control, or close to it, of at least four regional governments in addition to its own.

The pursuit of nuclear weapons, for all it is denied by Iranian officials, fits logically with Iran’s national security strategy. After all, while Iran may strike at its adversaries through proxies—until 2024, when it decided to confront Israel directly—it could not be assured that its adversaries would respond in kind, despite the Israeli and U.S. track record of doing just that. To forestall such an eventuality, Iran emphasized deterrence—vowing that a direct strike against the country would provoke any number of terrible consequences, whether a devastating Hezbollah missile barrage against Israel or strikes against U.S. personnel, interests, or partners in the Gulf, leading to the sort of regional war Tehran knew the United States sought to avoid. The possession of nuclear weapons would dramatically enhance this deterrence. Any country confronting Iran directly would be risking not just regional war, but a nuclear exchange.

To some extent, Israel has in recent months called Iran’s bluff. It finally struck Iran directly, breaking a taboo to which it previously paid lip service and that the United States fastidiously observed. Yet subsequent statements by regime officials evince no indication that their strategy has shifted, and if anything—with other tools of deterrence unavailable—nuclear weapons seem bound to play a more central role in that strategy. This underscores the fact that any significant shift in Iranian strategy toward coexistence and accommodation will likely require a change in regime. Iran’s current regime is invested in an ideology of anti-Americanism and rejection of Israel, and likely worries about the internal threat retreating from those tenets would pose to its own survival. If this is correct—i.e., that a strategic shift by Iran can only follow a significant political shift—then it follows that the United States and others concerned about Iran’s nuclear and regional policies should aspire for regime change in Tehran.

The difficulty with regime change as a policy objective, however, is that—unlike less ambitious goals such as disabling Iranian nuclear facilities—neither the United States nor Israel is certain of how to accomplish it. The U.S. track record at imposing regime change—whether in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, or elsewhere—is not encouraging. Even if U.S. and Israeli policymakers believed the results would be better in today’s Iran, it is not clear they know how to effectuate it short of an Iraq- or Afghanistan-style military occupation that few in the United States are prepared to contemplate. Even those American politicians who call for regime change in Iran are quick to qualify that it should not be accomplished by such means. As for other tools, the question of whether sanctions, military strikes, diplomacy, or alternative measures would weaken or strengthen the Iranian regime is fiercely debated even among those who agree on the desirability of regime change. As for President Trump, he has made his view on the topic clear: when asked weeks prior to his electoral victory about toppling the Iranian regime, he told an interviewer, “We can’t get totally involved in all that; we can’t run ourselves, let’s face it.”

Yet the inconvenient fact remains that barring significant political change, Iran is unlikely to fundamentally alter its approach to the United States or the Middle East. This likely applies to its nuclear pursuits as well. Those countries that have given up nuclear weapons or nuclear weapons programs have generally done so as a result of just that sort of political change, with Libya being the most notable exception. Keeping this in mind, three principles should guide the Trump administration with regard to regime change in Iran: (1) Do no harm—i.e., enact no policies likely to strengthen the regime; (2) Understand that lasting political change in Iran will necessarily be the work of the Iranian people—so support their efforts to the extent possible, and make no pledge to abjure such support; (3) Prevent the regime from obtaining a nuclear weapon, which would likely strengthen its grip on power and make any turmoil emanating from Iran far more perilous. It is often supposed that absent military action, the second and third goals are incompatible; however, U.S. policy toward the Soviet Union shows that this is not so. The United States engaged in both diplomacy and proxy conflict with the USSR without abandoning its policy of support for the Russian and other subject peoples, and without giving up its ultimate aspiration for regime change in Moscow.

Proposed Policy

President Trump and Vice President J. D. Vance have both made clear their preference for a diplomatic deal with Iran and their wariness regarding military conflict in the Middle East writ large. While such restraint is understandable given increasing U.S. military resource constraints and a priority placed on the Indo-Pacific, it may ultimately prove unrealistic. For better or worse, military strikes have a more successful record of stopping nuclear programs than does diplomacy—strikes in Iraq in 1981 and Syria in 2007 thwarted those states’ nuclear aspirations, whereas the Agreed Framework with North Korea (1994) and JCPOA with Iran failed to do so. These are imperfect comparisons, and critics would observe that it was the United States that withdrew from the JCPOA. This, however, is hardly conclusive. One of the difficulties with diplomatic resolutions to nuclear crises is that they require the sort of domestic buy-in that was not obtained in America for either the Agreed Framework or JCPOA; military strikes require no compromise with adversaries and cannot be undone by successors. Given Iran’s vulnerability and the advanced state of its nuclear program, the Trump administration would be remiss not to consider, and indeed prepare seriously for, military strikes against Iran’s nuclear program.

What’s more, the decision regarding military strikes is not exclusively an American one. As noted above, Israelis are actively debating whether to conduct military strikes on Iran. This may seem an elegant solution to many in the U.S. government, a way of destroying Iran’s nuclear program while steering clear of yet another military intervention in the region. Yet this line of thought neglects two problems with an Israeli military strike. First, Israel would almost certainly require U.S. support for any military action, through both military supply and defense against Iranian retaliation, perhaps among other things. U.S. forces will be in harm’s way even if America is not conducting the strikes itself; and given the possibility that Iran will retaliate against U.S. interests in Iraq and the Gulf, America will need to commit substantial forces to be prepared for such contingencies. Second, Israel has far lower military capabilities than the United States, which raises this question—if U.S. interests are likely to be targeted by Iran in retaliation anyway, should America not be the one conducting the strikes to ensure they are effective?

It is also important to note that however successful military strikes could be, achieving the same outcome via diplomacy—the track record noted above notwithstanding—would be less costly than military action. It might also hold other advantages military strikes would not, such as the installation of a mutually agreed verification and monitoring regime and greater opportunities for international cooperation and burden-sharing. The chief downsides of diplomacy are that it could, if mishandled, strengthen the Iranian regime politically and economically. These drawbacks, however, can be mitigated by the agreement itself—it must be sufficiently comprehensive to avoid conveying the impression that the regime has snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, and to ensure that Iran cannot funnel revenues gained from sanctions relief to its nuclear program or terrorist proxies, neither of which should be permitted to exist any longer.

Rather than choosing between diplomacy and military action, the Trump administration should think of these options as mutually supporting, sequencing its actions in hopes of achieving the best and least costly outcome. Washington must prepare for the possibility that U.S. or Israeli military action against Iran will be necessary. At the same time—taking advantage of a narrow window ending in September 2025, when the JCPOA provision allowing for the snapback of international sanctions on Iran must be exercised lest it expire—the Trump administration should pair mounting military pressure with increased diplomatic and economic pressure to obtain an agreement superior to the JCPOA, which would obviate any need for strikes. On the other hand, if diplomacy fails, a sincere effort to negotiate a deal would presumably aid in attaining the necessary domestic and international support for a military option. U.S. policy during this period should consist of the following components (although note that this would not constitute the entirety of U.S. policy toward Iran, which should also encompass matters outside the scope of this paper, such as supporting the Iranian people, countering domestic threats in the United States and cyber threats, etc.).

Track One: Pressure

The Trump administration has an opportunity to harness the existing EU-led diplomatic pressure campaign against Iran, along with Israel’s military campaign against Iran, and add economic measures that could bring comprehensive pressure to bear on the regime in short order.

Diplomatic pressure. In its November 2024 resolution censuring Iran, the IAEA Board of Governors requested that the agency produce a “comprehensive report” on “the possible presence or use of undeclared nuclear material in connection with past and present outstanding issues regarding Iran’s nuclear program, including a full account of Iran’s cooperation with the IAEA on these issues.” The IAEA report could serve as a basis to refer Iran to the UN Security Council, where, assuming that Russia and China block more serious action, Britain or France could initiate the sixty-day snapback process. That process would ideally conclude in September 2025, as Russia holds the rotating presidency of the Security Council starting in October; this implies that snapback must be initiated sometime in July.

Economic pressure. Iran is currently exporting nearly 2 million barrels per day of oil, up from less than 400,000 bpd in 2020. The lion’s share of these exports are bound for small “teapot” refineries in China, while China’s larger refiners—which have greater exposure to Western sanctions—purchase crude oil from Russia and other suppliers. While these teapot refineries may be difficult to influence through sanctions, the sales involve a spider’s web of other actors who may be far more subject to influence—whether the countries like Malaysia involved in transshipping the oil to obscure its origin, to the shadow fleet of tankers employed to transport it, to the front companies and banks used to sell the oil and repatriate revenues to Iran. The Trump administration could likely dent Iran’s oil sales quickly through early, strong signals of intent to aggressively pursue any entities involved in this trade. While at first blush the parlous state of U.S.-China relations may seem to complicate this task, in reality Beijing may see restricting oil purchases from Iran as a low-cost gesture to President Trump. Such is the superficial nature of what is often grandiosely labeled an Iran-China “axis.” Increased oil production by the United States, as reportedly planned by the Trump administration, holds the prospect of further driving down Iranian revenues by decreasing oil prices.

Military pressure. Iran is already under tremendous military pressure due to the October 2024 Israeli strikes that reportedly degraded both its air defenses and much of its offensive missile capabilities. That pressure is likely only to build as military strikes on Iran’s nuclear program are openly discussed. The Trump administration should nevertheless add to this pressure, making clear its own willingness to use force rather than simply back Israel. This can be accomplished in three ways: (1) President Trump should explicitly state his intention to continue President Biden’s policy of surging military support into the region to support Israel, and should back up this assertion by providing Israel military articles and training necessary for strikes and conducting joint military exercises with the Israel Defense Forces; (2) He should reiterate his first-term policy of exacting immediate and painful retribution for any attacks on U.S. personnel or interests, including by Iranian proxies such as the Houthis; (3) Trump should ask Congress for authorization to use military force directly against Iran, a necessary step for mounting strikes should diplomacy fail.

Track Two: Diplomacy

The pressure campaign described above would support diplomacy aimed at compelling the Iranian regime to make significant changes to its policies. One of the most significant flaws of the 2015 JCPOA was that it addressed only Iran’s nuclear activities, and those partially and temporarily. Any new diplomatic understanding must comprehensively end Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons while also addressing the regime’s malign regional activities, although not necessarily as part of the same initiative or agreement.

Nuclear. In negotiating a nuclear agreement with Iran, the Trump administration must bear in mind the chief flaws of the JCPOA, as discussed below. It should work closely with the E3 and consult regional allies, but eschew the P5+1 framework that permitted Russia and China to delay and dilute sanctions in exchange for their support at the UN Security Council (the P5+1 refers to the five permanent members of the UN Security Council—China, France, Russia, the UK, the U.S.—plus Germany.)

- Prominent among the JCPOA’s flaws was that Iran was permitted to escape the strategic choice between keeping its nuclear weapons option on one hand and enjoying sanctions relief and reengagement with the West on the other. Instead, it was permitted both, albeit with restrictions. Any new nuclear deal must require Iran to finally confront that choice, dismantling and exporting its nuclear infrastructure if it wishes to enjoy the deal’s benefits.

- In addition, the JCPOA was asymmetric in its timeframe. The commitments required of the United States were permanent, whereas the restrictions imposed on Iran were temporary. In this sense, the deal was not about ending Iran’s nuclear weapons capability but about “rehabilitating” Iran under the NPT so that it would eventually be treated like any other signatory—a shift in narrative engineered by then Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif. Any new deal must be balanced—one side’s commitments end only when the other’s do, as in the case of other nonproliferation treaties.

- Vital in any such deal will be:

- Defining what precisely constitutes Iran’s nuclear program, which sprawls across civilian and military sites alike, as well as research institutions including universities

- Ensuring that definition includes Iran’s nuclear-capable missile and space launch program

- Fully accounting for past nuclear activities and specifying robust verification and monitoring measures, including ones designed to address the shortcomings of the JCPOA—especially its vagueness about weaponization activities—which allowed Iran to deny access to IAEA inspectors for years with few consequences

- Obtaining congressional buy-in to secure sanctions relief

Regional. The other oft-cited JCPOA flaw is that it was a “nuclear only” deal, and did not address regional issues. While Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons poses the most significant threat to the United States, its other regional policies—supporting terrorism, proliferating advanced missiles and drones, and others—also threaten American interests as well as the stability of the Middle East and security of U.S. partners there. In addition, it is important to bear in mind that Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons and its destabilizing regional activities are part and parcel of a single strategy, detailed above. If Iran is willing to compromise on one but not the other, Washington should take this as a signal that the regime is unwilling to move away from that strategy decisively and that whatever accommodation it is offering is tactical and likely fleeting.

Nevertheless, the Trump administration should be wary of pursuing a so-called grand bargain with Iran covering both nuclear and regional issues, for three reasons: (1) Doing so may inadvertently convey the impression that the United States considers Iran its counterpart in addressing regional issues; (2) Iran may not view as credible a U.S. threat to walk away from a grand bargain over violations of promises regarding regional activities, given Washington’s clear prioritization of nuclear issues and desire to shift attention to other regions; (3) This approach would not just sideline regional partners but relieve them of any burden of holding Iran accountable to an acceptable standard of behavior in the region. What’s more, a “grand bargain” may inadvertently constrain the United States as much as it does Iran, and Washington should preserve its freedom to act against groups like Hamas, the Houthis, and Shia militants in Iraq.

Instead, the U.S. administration should ask its key partners in the Gulf, such as Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, to lead a negotiation on regional issues with Iran, not with an eye toward “sharing” the region as President Barack Obama famously advised, but rather toward securing pledges from Iran to end its destabilizing behavior. One way to frame such an agreement would be to establish norms of behavior to stabilize the region after more than a year of convulsive conflict. Such norms, in stark contrast to current Iranian policies, would necessarily include (but not be limited to) refraining from supporting nonstate actors; refraining from proliferating UAVs, missiles, and other dangerous technologies; respecting the sovereignty and territorial inviolability of regional states; refraining from hosting Russian and Chinese military forces; and refraining from seeking the destruction of any regional state, whether or not it participates in the negotiations. The United States would need to make clear to Tehran that Washington’s continued adherence to any nuclear deal hinges on Iranian compliance with such a regional accord.

The above constitutes an ambitious agenda for the first nine months of 2025. But adhering to a firm deadline, however uncomfortable for U.S. officials, will enhance American leverage in talks if Iran views as credible the threat to walk away and pursue a military alternative.

Alternative Scenarios

While in the author’s view the above policy path is the one most likely to durably advance U.S interests, the Trump administration must also be prepared for other scenarios.

- Preemptive Israeli strikes. Even as it follows the path prescribed above in coordination with Israel, the Trump administration will need to plan for the possibility that Israel will move ahead more expeditiously with military strikes, or that another round of Iran-Israel conflict hastens those strikes. This will require planning not just for the strikes themselves, including any needed U.S. support for Israel and efforts to protect American and partner interests, but consideration of next steps. In the aftermath of an Israeli strike, the United States will need to assess the extent to which Iran’s nuclear program has been set back—most likely in the absence of UN inspectors, who either will have left or, especially if Iran withdraws from the NPT as threatened, have been expelled. If Israeli strikes do not reliably eliminate Iran’s ability to achieve a nuclear breakout, a new strategy to address Iran’s residual nuclear capabilities—whether focused on diplomacy or follow-up strikes—will be needed.

- Covert Iranian breakout. Given the advanced state of Iran’s nuclear program and the degradation of the IAEA inspection and monitoring regime, the Trump administration—even as it executes its preferred policy—may receive information indicative of an Iranian breakout attempt, such as the diversion of 60 percent–enriched uranium. To prepare for such a scenario, the United States must continue to invest sufficient intelligence resources in monitoring Iran’s nuclear activities. It should also develop, together with Israel and other allies, common guideposts on what would indicate an active Iranian breakout attempt, and game out both the timing and nature of a joint response to such indicators. Because Iran could develop and test a rudimentary nuclear device in relatively short order, this work must be undertaken in advance rather than waiting for the initial indications of a breakout, which may in any case be confusing and contested.

- Containment. An alternative to diplomacy and military strikes is containment, which is essentially the policy the United States has been pursuing off and on for nearly three decades. In this scenario, America seeks to counter and deter Iranian regional activities while stymieing Iranian nuclear progress through economic sanctions, export controls, and military threats, in the hope that such measures can prevent an Iranian nuclear breakout long enough to outlast the current leadership. While this policy has arguably succeeded in preventing Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons to date, this success is not guaranteed to be replicable in the future given the advanced state of Iran’s nuclear enterprise, nor has it proven as successful in addressing Iran’s regional activities. The passage of time would also allow for additional complicating developments—deepening Iranian military cooperation with Russia or China, for example, could raise the stakes of any Israeli or U.S. military action. Furthermore, pursuing this policy would mean forgoing the opportunity presented by Iran’s present weakness.

- “Photo op” diplomacy. Iran may hope that it can escape its current dilemma simply by currying President Trump’s favor, offering historic “firsts” such as presidential summits along with vague declarations of non-enmity and pledges to eventually negotiate a deal stronger than the JCPOA. Tehran would pursue such a gambit squarely with the goal of kicking the can down the road—surviving a moment of vulnerability, and perhaps avoiding sanctions snapback as well. This scenario, although it would have serious consequences, must be considered unlikely, since it would require both Israel’s acquiescence and—perhaps more unlikely—Iran’s setting aside of the anti-Americanism so central to the regime’s ideology.

Michael Singh is the Lane-Swig Senior Fellow and managing director at The Washington Institute. This project was supported by Bruce and Leslie Lane and Cissie Swig—patrons of the author’s fellowship.