If Assad and his allies stick with their past strategy, the initial offensive will likely be limited, though it will still spur massive refugee flows and a serious breach between Turkey and Russia.

CLICK ON ANY MAP TO VIEW OR DOWNLOAD A HIGH-RESOLUTION VERSION.

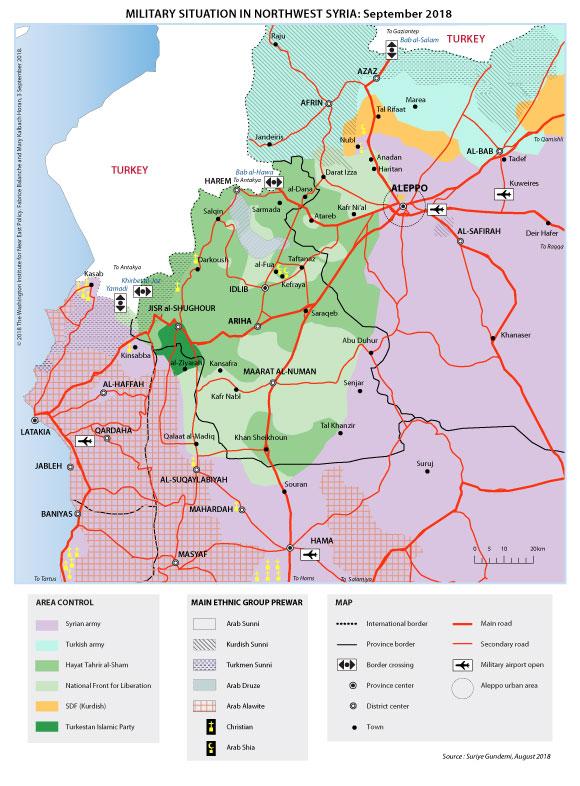

The Assad regime’s brewing offensive against Idlib, the last major rebel pocket in Syria, will take place soon. Army troops have been massing on the enclave’s border for weeks, while preparatory airstrikes and shelling have begun. Various international actors publicly oppose the imminent campaign, including Turkey, which wants to protect its local rebel proxies and long-term strategic interests in Syria. Yet Damascus and its allies in Moscow and Tehran seem indifferent to Ankara’s dissatisfaction, and they will not be deterred by other outside warnings either.

IDLIB REBELS ARE NUMEROUS BUT DIVIDED

In March 2016, rebel forces numbered between 50,000 and 90,000 in the Idlib pocket. The broad range in this estimate was due to ambiguities in combatant status: while some 50,000 of these rebels were full-time fighters belonging to top groups, another 40,000 were casual fighters belonging to small local factions that may not be willing or able to appreciably affect a major battle. These fighters have been reinforced by about 20,000 other rebels expelled from Aleppo, Ghouta, Deraa, and Rastan, areas the regime and its allies have retaken in the past two years. Yet some of the rebels in the pocket have since been killed, left Syria, or moved to areas occupied by Turkey (Afrin, Azaz, Jarabulus, or al-Bab). Evaluating the exact number in Idlib today is therefore difficult, but it is certainly much larger than the 30,000 figure generally quoted, probably double that.

The rebels are split into two coalitions of more or less equal numbers: Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), led by al-Qaeda affiliates, and Jabhat al-Wataniya al-Tahrir (JWT, aka the National Front for Liberation). Turkey created the latter coalition this May to weaken HTS, rally its opponents, and prevent it from taking over the entire pocket, since Ankara’s initial goal of dissolving HTS proved unsuccessful. JWT’s eleven factions include remnants of the Free Syrian Army and Ahrar al-Sham.

Until earlier this year, HTS was content to control the border with Turkey, Idlib city, the province’s main lines of communication, and various strategic points, effectively extending its grip over most of the pocket. In February, however, conflict broke out between HTS and Turkish-backed rebels, resulting in a more heterogeneous division of territory after their May ceasefire. HTS now controls most of northern Idlib, while it has had to abandon the southern part of the pocket and the western periphery of Aleppo to JWT. Yet the southern rebels are isolated, caught between the hammer of HTS and the anvil of the Syrian army. Ankara can hardly supply them—in fact, the Turkish military has to negotiate with HTS just to send soldiers and equipment to its own observation posts on the frontlines with the Syrian army. JWT would therefore be the first target if the offensive begins in the south, which appears to be the most logical strategy for Damascus and its allies.

ATTACKING THE WEAKEST SPOT FIRST

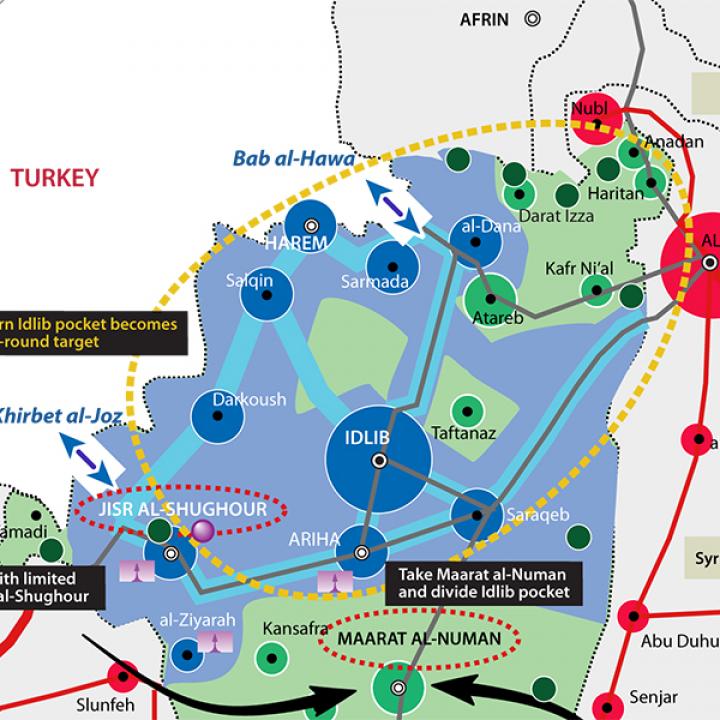

Although Bashar al-Assad seemingly aims to retake all of Idlib, he will likely be content at first with a limited offensive given the size of the rebel forces there (not to mention the political value of keeping the HTS threat alive but contained, as discussed in greater detail below). The regime’s primary purpose is to provide better protection for Latakia and the Russian base at Hmeimim, which have been targeted regularly by rebels located around Jisr al-Shughour. Its second objective is to push rebels further away from Hama by seizing the entire southern part of the Idlib pocket up to Maarat al-Numan. Another objective may be to clear rebels from the western periphery of Aleppo.

Given these apparent objectives, the Turkish-backed rebels will likely be the first targets of the coming offensive. Recent shelling may indicate that Jisr al-Shughour is another potential early target, but any Syrian army thrust there would involve confronting Uighur fighters from the Islamic Party of Turkestan, a faction that is poorly integrated with other rebels given its ethnic particularism yet still dangerous on its own—and, like leading elements of HTS, loyal to al-Qaeda. Moreover, the terrain surrounding the city is steep and would take months to retake with infantry, as was the case in Salma to the west of Jisr al-Shughour. The difficulty of any such operation may deter the army from trying to seize the city immediately; the current shelling there may instead be intended to neutralize the Uighurs.

In contrast, the army would have an easier time seizing al-Ghab plain and the low areas around Jabal al-Zawiya, where air and armored forces can crush rebel defenses. Syrian troops from the west could then converge with those coming from Abu Duhur to seize Maarat al-Numan, essentially cutting the Idlib pocket in half. The remaining pro-Turkish rebels in the south would find themselves encircled and forced to surrender, perhaps with an offer of refuge in Turkish-controlled areas such as Afrin or Jarabulus. The army has previously used this strategy in Ghouta, Aleppo, Rastan, and Deraa: that is, dividing a rebel territory by attacking the weakest faction first, then negotiating with separate factions individually. The army and its allies are likely counting on HTS to remain largely neutral at first, calculating that the coalition will quietly watch its rivals get eliminated and then absorb their disappointed remnants for round two of the battle for Idlib.

TURKEY’S DILEMMA

Ankara is of course sharply opposed to this strategy. Such a campaign would exact the heaviest toll on JWT, damaging Turkey’s credibility with local allies who have committed to stand against HTS. Ankara demands that the offensive be postponed, but Damascus, Tehran, and Moscow argue that Turkey has not fulfilled its commitment to eliminate HTS, so they have no choice but to cleanse Idlib themselves.

In fall 2017, a regime offensive against the Idlib pocket allowed Damascus to retake a southeastern slice of it, including Abu Duhur military base. Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan was furious about that operation and publicly threatened Damascus for attacking his proxies. In the end, Russia appeased him by giving him a green light to attack the Kurdish area of Afrin. Damascus may intend to offer similar compensation for the next Idlib campaign, well aware that eliminating the Kurdish People’s Defense Units (YPG) remains Turkey’s top priority in Syria. Yet the U.S. military presence in the northeast would prevent any new Turkish offensive against the Kurds even if Erdogan received another green light from Moscow, so it is unclear how far he will take his opposition to the next Idlib campaign.

Whatever the case, eliminating JWT would enable Damascus to get rid of a few more factions that might have represented the opposition at the negotiating table. As part of the counterinsurgency strategy it has followed since 2011, the regime has steadily targeted moderate rebel groups so that only radical factions like HTS remain. The international community is fearful of such radicals and does not consider them a political alternative to the regime or a viable negotiating partner. Assad may therefore be willing to keeping hemming them in without confronting them head on in order to stave off outside efforts to topple him.

For its part, Turkey has tried in vain to convince HTS to break with jihadist ideology and integrate with JWT. Had it succeeded, Ankara would have gained strong leverage over Damascus, perhaps enough to make the Idlib pocket a Turkish protectorate like north Aleppo and incorporate it into the buffer zone Erdogan has been forming on Syria’s side of the border. Yet the fact that HTS has pushed JWT and other rivals almost entirely out of northern Idlib calls this scenario into question, since this would essentially mean creating a sanctuary for al-Qaeda.

CONCLUSION

Many unknowns remain about the scale and outcome of the coming battle for Idlib. Yet if Damascus and its allies stick with their past strategy, the upcoming offensive will likely be limited, albeit for strategic rather than humanitarian reasons. Hundreds of thousands of civilians will still flee to the north of the province, requiring a major humanitarian response in a zone controlled by hostile radicals. Yet the battle itself might not be so bloody—at least the first round against Turkish-backed rebels.

If and when a second round is launched against HTS in northern Idlib, it could be a different order of magnitude. Moscow, Tehran, and Damascus would likely try to use overwhelming force there, arguing that the goal of eliminating al-Qaeda from the area would justify gross humanitarian violations. Although this Machiavellian plan might succeed in military terms, it would seriously damage relations between Russia and Turkey. The battle for Idlib may therefore represent an opportunity for U.S. rapprochement with Ankara, especially if Syrian or Russian forces target the Turkish observation posts dotting the rebel pocket.

Fabrice Balanche is an assistant professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2.