- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3055

In the Scramble to Save the Iran Deal, Don’t Forget Procurement

A new UN report does little to assuage concerns about suspicious Iranian procurements, underscoring the need for allied intelligence agencies to boost their detection efforts.

In the past few weeks, the UN Security Council has released three reports related to Resolution 2231, each providing updates on Iran’s compliance with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and its suspicious acquisitions outside the official procurement channel set up under the JCPOA. Any hopes for detailed updates were dashed, however; instead, the reports underscored how the UN Secretariat and the International Atomic Energy Agency remain reliant on weak self-reporting mechanisms to verify and monitor procurements, thus fostering the possibility of Iran illicitly or covertly obtaining nuclear items. The United States should proactively reach out to its European allies—especially remaining JCPOA parties—to buttress UN and IAEA efforts and ensure continued vigilance against potential Iranian subterfuge.

A SUBTLE COMPLAINT SPEAKS VOLUMES

On November 26, the Security Council released the most recent IAEA report on Iran and the JCPOA. As in past reports, it reiterated Tehran’s continued compliance with the deal’s nuclear-related provisions, but also raised concerns about the government’s responsiveness to IAEA requests. Specifically, the agency nudged Iran to provide more “timely and proactive” cooperation—wording that the U.S. assistant secretary of state for international security and non-proliferation, Christopher Ford, called a “pointed complaint,” despite being couched “in the muted discourse of IAEA diplomacy.”

The agency can likely provide more detailed information to JCPOA parties in private about delayed Iranian compliance. Armed with that information, governments can then buttress the IAEA’s verification efforts by holding Iran accountable to its JCPOA obligations.

SUSPICIOUS ACTIVITY

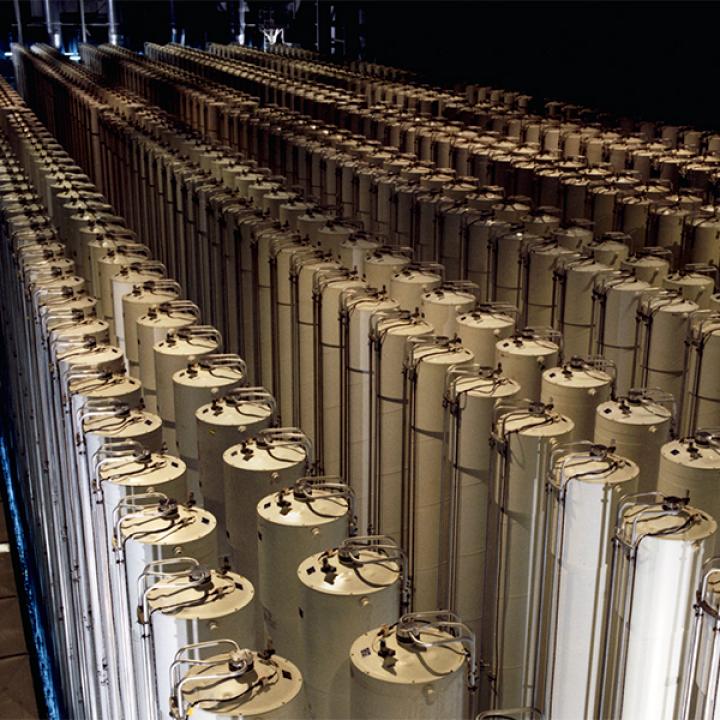

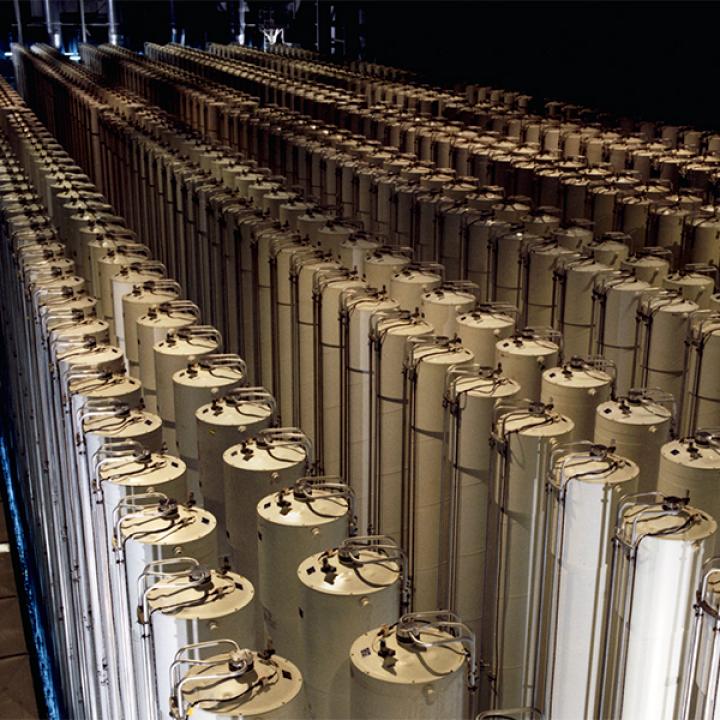

On December 6 and 11, respectively, the UN Secretariat and the facilitator for implementation of Resolution 2231 released their latest reports on matters such as the procurement channel and suspicious activity occurring outside of it. After U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, it appears as though the procurement channel—a mechanism established to monitor transfers of material, equipment, and other assistance required for Iran’s nuclear program—is continuing to operate, albeit at a reduced rate. In their previous reports, issued June 2018 and covering the last few months of U.S. participation in the JCPOA, the channel received thirteen transfer requests. In the two reporting periods before that, it received eight and ten requests. In the latest period, however, it received only five.

As expected, the reimposition of U.S. sanctions against Iran in August and November made some of the activity in the procurement channel sanctionable under U.S. law, which may have deterred submissions. The channel’s already limited use makes it difficult to confirm this hypothesis, but the next batch of reports—in six months, after U.S. sanctions have been given time for implementation—may shed further light.

Unfortunately, but unsurprisingly, the latest reports provide limited clarification on suspicious activity occurring outside the channel, including incidents noted in the previous reporting period. According to the June reports, the Security Council was investigating U.S. and Emirati claims that Iran had obtained dual-use items—that is, materiel transferred under commercial, non-nuclear auspices but which could be used in a nuclear program—independent of the procurement channel. Specifically, UAE officials stated that Iran had received “40 cylindrical segments of tungsten, 1 inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer, 10 capacitors, and 1 titanium rod.” The December reports explain that, according to the unidentified countries of manufacture, the tungsten and capacitors did not meet the criteria necessary to require approval from the procurement channel.

Yet the country of manufacture for the spectrometer told the UN Secretariat that the item did meet these criteria, though an internal review was still ongoing, leaving readers to wait for final confirmation. As for the suspect titanium rod, the Secretariat’s report indicated that no further information was available. It also failed to make any determination on the carbon fiber and fifty tons of aluminum alloys that Iran received outside the channel, despite previous U.S. assertions that they should have been subjected to approval. As previously described in detail, it would be highly troubling if these items meet certain criteria and Iran procured them outside the channel, since each of them can be used in a nuclear or missile program. Reflecting its limitations on these matters, the Secretariat said simply that it has “sought clarification” on each case.

WEAK COUNTERPROLIFERATION MECHANISMS

The Secretariat’s latest report dramatically underscores the lack of trustworthy mechanisms in place to investigate subterfuge. This deficiency is not new, but it may be exacerbated by U.S.-European disagreement over Washington’s decision to pull out of the JCPOA.

Currently, in cases of alleged illicit procurement, the country of manufacture is required to tell the Security Council whether the item in question meets the specifications necessary for review by the channel. No outside party verifies the information supplied by said country—not the UN, not the procurement channel working group, and not any other agency, let alone one with the technical knowledge required to test the veracity of the claims. This is reminiscent of IAEA verification and monitoring mechanisms that put the onus of reporting and clarifying on the accused. Fears of an international agency encroaching on sovereignty may explain why a proper, thorough investigatory function has never been set up through a UN body. In any case, the end result is that Iran could exploit these loopholes to procure illicit items. Shockingly, even if the weak mechanisms in place do find evidence of illicit procurement, the onus for explaining the violation falls on the supplier, not the buyer. In effect, Iran can procure items outside the official channel with little fear of consequence.

The intelligence agencies of the United States and the JCPOA parties, using their detection capabilities to full effect, can help address this problem, as they have in the past. A joint counterproliferation effort of this sort requires firm political will and active coordination between states—perhaps a difficult prospect given the political divisions that surfaced after U.S. withdrawal from the agreement.

Europe should be lauded for its efforts to save the JCPOA and ensure that Iran does not withdraw and subsequently reinvigorate its nuclear program. Yet in the public scramble to save some aspects of the deal, it is essential that they privately bolster their counterproliferation efforts—or else risk confirming U.S. suspicions about the deal.

Elana DeLozier is a research fellow in The Washington Institute’s Bernstein Program on Gulf and Energy Policy and a former nuclear analyst in the New York City Police Department’s Counterterrorism Bureau.