Although it is still too early to write the prime minister off as an Iranian lackey, he is on a familiar trajectory for Iraqi governments: doing the minimum necessary to prevent deterioration with Washington while satisfying the voracious demands of his Iran-backed partners.

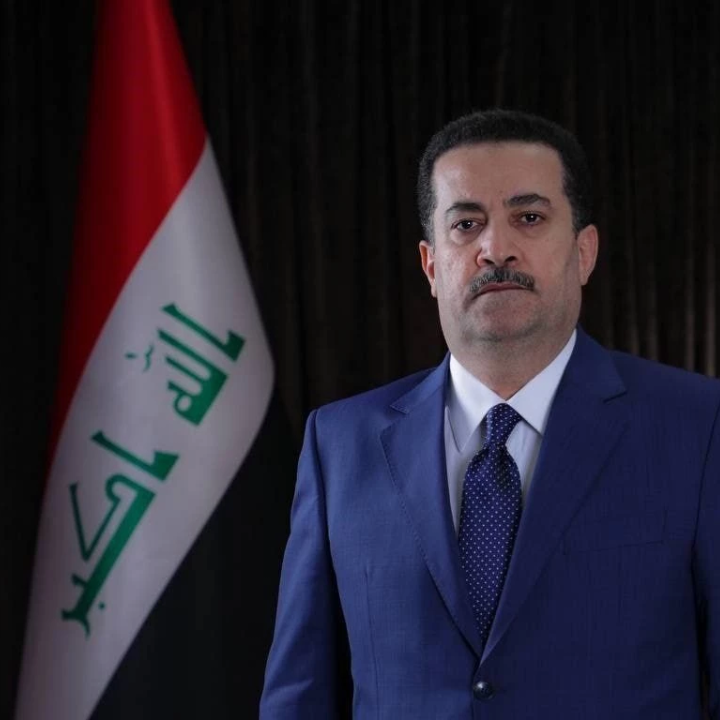

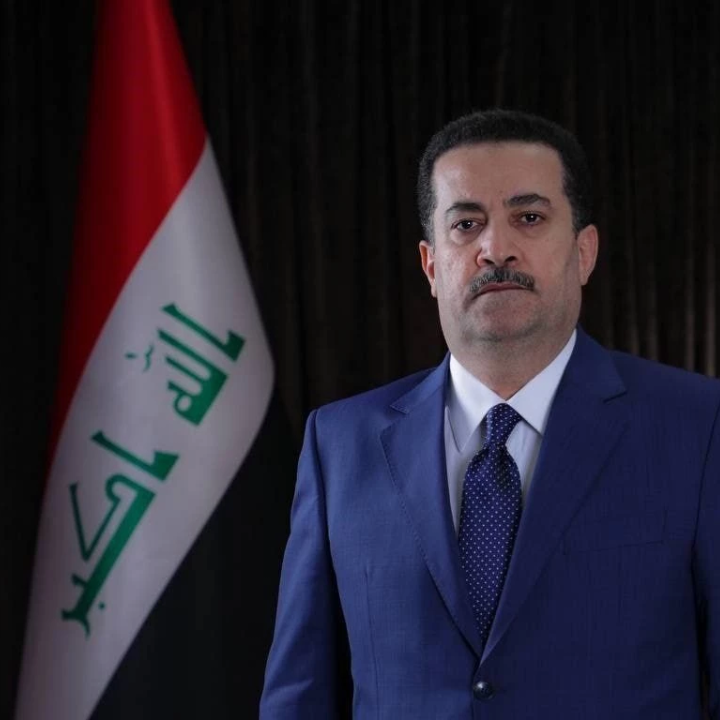

On January 16, Iraqi prime minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani hosted talks with Brett McGurk, the U.S. National Security Council coordinator for the Middle East and North Africa. Shortly afterward, Sudani reportedly hosted Esmail Qaani, the head of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Qods Force. The close sequencing of these meetings highlights the precarious balancing act that the new premier is still performing nearly 100 days into his term. Because he arrived at his post via support from the Iran-aligned, militia-run parliamentary coalition known as the Coordination Framework (CF), it remains unclear whether he is committing to an independent Iraq with strong ties to the United States or adopting the same posture many of his predecessors did: placating Washington while quietly positioning Baghdad alongside Tehran. The early indications are not promising.

Disposition of U.S. Forces

Ever since the January 2020 death of Qaani’s predecessor, Qasem Soleimani, the presence of U.S. military forces has become somewhat of a litmus test issue for Iraqi politicians. Following the U.S. operation that killed Soleimani and militia leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis while they met in Baghdad, the parliament passed a nonbinding resolution demanding the immediate withdrawal of American troops. Yet while the deployment has gradually downsized, consolidated, and nominally transitioned from a combat role to an advisory role, nearly 2,500 U.S. soldiers remain. Not surprisingly, some CF factions continue to vocally oppose this presence; most recently, Fatah Alliance chief Hadi al-Ameri publicly reiterated his longstanding demand for a full U.S. military departure.

On this issue at least, Sudani appears to be standing firm. In a January 15 interview with the Wall Street Journal, he advocated a continued U.S. troop presence to ensure the abiding defeat of the Islamic State. His support for the U.S.-Iraq Strategic Framework Agreement—which states that the American presence is “at the request and invitation” of the Iraqi government—may not please his CF partners, but he will likely be able to continue deflecting this issue for the near term. Notably, however, even this stance may hinge on two conditions: if Sudani’s government crafts a budget that provides sufficient patronage to the CF, and if Iran and its Iraqi partners remain willing to tolerate the U.S. presence despite their rhetorical bluster.

Legal Challenges, Smuggling, and “Gulf” Terminology

Earlier this month, Iran’s Foreign Ministry dispatched a delegation to Baghdad on the third anniversary of Soleimani’s killing. Its reported purpose was to press Sudani about characterizing the late commander as an “official guest” at the time of his death—a ploy that would give Tehran more leverage for conducting “lawfare” against Washington. The request is a test for Sudani, who seemingly understands that acceding to Tehran on this matter would complicate relations with the United States and attenuate its economic and security benefits. Thus far, the prime minister has condemned Soleimani’s targeted killing as “a flagrant violation of Iraqi territory and sovereignty,” but he has yet to meet Tehran’s “official guest” request or formally agree to establish a joint court with Iran to internationalize the case. Sudani’s coalition partners consider Soleimani a martyred hero, so they will likely continue pressuring him on both counts.

Elsewhere, the prime minister appears to be cooperating with a U.S. Treasury Department initiative to limit the smuggling of dollars to Iran, among other states. Such trafficking—perpetrated in large part by Iraqi militias—has helped bolster the Iranian regime while undermining Iraq’s economy. Hence, enforcing the relevant U.S. Treasury strictures can help limit corruption, reinvigorate Iraq’s banking sector, and fuel the local economy. Although taking this step is no doubt unpopular with many of Sudani’s coalition partners, there is little political cost for him because he can honestly say he was compelled to do so by Washington. Even the CF is well aware that the United States is doing the government a favor by transferring roughly $1 billion per month in Iraqi oil revenue from the U.S. Federal Reserve to Baghdad.

A less controversial matter is the renewed demand that Baghdad comply with Iranian geographic terminology. Earlier this month, Iraq hosted the Arabian Gulf Cup for the first time since 1979. Organizing and ultimately winning the region’s premier soccer competition was a proud moment for Iraq, since the country had been banned from international competition during the Saddam era and subsequently unable to play host due to security reasons. Yet Iran’s Foreign Ministry has sullied the celebration by lodging a complaint and requesting an apology for Iraq’s use of the term “Arabian Gulf” during the tournament instead of “Persian Gulf.” This appeal has little resonance for Iraqis, even those in the CF beholden to Iran, so it poses little urgency for Sudani. In fact, rejecting this largely symbolic demand may give him domestic political leeway to meet more substantive Iranian requests.

Cabinet Appointments and Business Transfers

Early on, Sudani stoked controversy by selecting members of the U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization Asaib Ahl al-Haq (AAH) to serve as minister of higher education and head of communications in his personal office. While those moves were unfortunate, his choices for sovereign ministries (e.g., Defense and Foreign Affairs) have not raised concerns in Washington—rather, they have inspired confidence.

Even so, critics of Sudani argue that other appointments made since then are sops to his Iran-backed coalition partners. This week, with the dinar devaluing sharply against the dollar, Sudani appointed a new Central Bank governor: Ali Mohsen al-Alaq, who formerly served in that post and is believed to be sympathetic to the State of Law Alliance, the largest partner in the CF. Alaq was no doubt the preference of Nouri al-Maliki, the corrupt former prime minister who heads the alliance and has become the de facto kingmaker in Iraq. Maliki is also reportedly pressing Sudani to install several cronies in top spots at the Ministry of Oil.

On the security front, the prime minister has appointed AAH officials to pivotal positions in the Iraqi National Intelligence Service. He has also rehired many previously dismissed intelligence officers affiliated with Iran-backed militias.

Beyond individual appointments, Sudani transferred management of the government-owned and -capitalized “Muhandis” company to Iran-backed militias late last year—a move that had been put on indefinite hold by his predecessor Mustafa al-Kadhimi. Named after the late militia leader killed alongside Soleimani, this umbrella company has a diverse portfolio of businesses in the construction, investment, telecommunications, military production, and hospitality sectors. As such, it will provide the militias—many of which have been designated by Washington for terrorism and corruption—with alternate revenue streams similar to those that bolster the Revolutionary Guards in Iran.

Conclusion

The Washington Institute’s Militia Spotlight platform recently described an apparent division of labor between Sudani’s government and the Iran-backed militias. According to AAH leader Qais al-Khazali, Sudani will act as the “general manager” of a “resistance”-led government, highlighting the symbiotic relationship between violent armed groups and the seemingly moderate prime minister.

Indeed, Sudani is clearly trying to have it both ways, and his CF coalition partners seem to have little problem with this approach so far. For the militias, the most important issue is patronage, which Sudani is already doling out to them in the currency of senior government positions and, soon enough, budgetary perquisites. For example, the budget surplus from the recent spike in oil prices will reportedly be used to hire an additional 300,000 government employees—a massive distribution of patronage that will no doubt benefit the prime minister’s coalition partners.

Although it is still too early to write Sudani off as an Iranian lackey, he is on a familiar trajectory for Iraqi governments: namely, doing the minimum necessary to prevent deterioration with Washington while satisfying the voracious demands of his Iran-backed partners. He will no doubt have great difficulty fighting corruption and improving the economy so long as he kowtows to diktats from Iran and its local allies. Yet this is exactly what he appears to be doing at the moment, if only to forestall early elections that could bring back his vanquished rival Muqtada al-Sadr.

David Schenker is the Taube Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute and director of its Program on Arab Politics.