- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3967

Supporting the SDF in Post-Assad Syria

To preserve its only reliable and capable partner in the fight against the Islamic State, the United States must help the SDF deter HTS and fend off Turkey-backed militias.

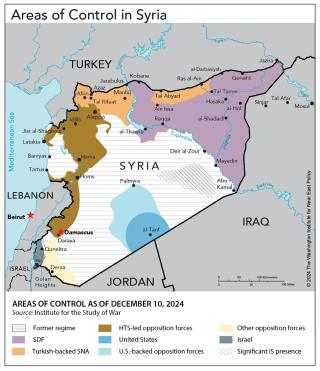

Bashar al-Assad’s fall has quickly changed the map of Syria. While the jihadist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and its allies swept out of their base in Idlib to seize major regime strongholds en route to the capital, other opposition groups moved to take territory in the southeastern provinces of Deraa and Quneitra. In the central and southern Badia desert region, the U.S.-backed opposition faction Maghawir al-Thawra has expanded its control around the American garrison at al-Tanf. Remnants of the Islamic State (IS) prowl the desert too, liable to strike at any moment. And in the northeast, the U.S.-backed, Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) moved deeper into Raqqa but lost ground in Tal Rifaat and Manbij due to advances by the Syrian National Army (SNA), the local coalition of Turkey-backed militias.

At this fragile moment, U.S. officials must reassess the SDF’s needs to ensure it has the support required to continue the mission that brought the two partners together in the first place—the shared fight against IS, which now includes defending the many northeastern detention facilities that hold thousands of IS members and supporters. This task also entails keeping SNA militias at bay and ensuring that the SDF is prepared to face a renewed HTS offensive if the jihadists decide to push into the northeast.

Shifting Balance of Power

Although Assad and the SDF were rivals, the regime and its backers in Iran and Russia developed an uneasy but relatively stable modus vivendi with the group in recent years. Assad mostly left the SDF alone in the northeast, while the SDF agreed that the regime and its foreign allies would control small parts of Hasaka and Qamishli inside SDF territory, including Qamishli Airport and the nearby border crossing with Turkey. Meanwhile, U.S. forces have been present in the northeast since 2015 to help the SDF combat IS, while also serving as a de facto deterrent against Iran, Russia, Turkey, and Assad.

As part of these arrangements, forces from the Assad regime, Russia, and the SDF cooperated to patrol SNA frontlines and the Turkish border, with the aim of deterring Ankara from further offensive operations. Turkey considers the main Kurdish contingent within the SDF as a terrorist entity given its links to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), and ultimately seeks its destruction. Following a series of operations in northern Syria in 2016-17 and 2018, Turkish forces launched a major incursion in 2019, creating a 100-mile-wide “buffer zone” inside SDF territory between Ain Issa and Tal Tamer. Afterward, Ankara and Moscow signed a memorandum of understanding that established joint Russian-Turkish patrols on Turkey’s side of the zone and joint Russian-SDF-regime patrols on the SDF side. (As of this writing, it is unclear to what extent Russian forces remain in this area.)

The delicate balance of power in the northeast held even as Iran and Assad tested the SDF’s resolve earlier this year by sending Arab tribal fighters to attack its positions in Deir al-Zour. Yet the regime’s collapse and the deterioration of Russia and Iran’s presence have upset this balance. On one hand, the SDF has taken full control of many abandoned regime positions and expanded into central Syria. On the other hand, SDF deterrence against Turkey and the SNA has dissipated, and HTS has emerged as a potent new rival.

Renewed Turkish and Jihadist Threats

HTS and the SNA are rivals, but they may choose to quietly cooperate against the SDF in the new environment, or at least stay out of each other’s way. Both have benefitted from Turkish support, though HTS is an independent jihadist group while the SNA is a Turkish proxy that includes Islamist and non-Islamist factions.

When the latest HTS offensive smashed regime positions in Aleppo, it exposed the nearby SDF enclave of Tal Rifaat to SNA assaults. On November 30, the SDF sent reinforcements to open an evacuation corridor, but SNA forces quickly cut them off with the help of significant Turkish artillery and air support, trapping them in Sheikh Maqsoud, a Kurdish-majority neighborhood in Aleppo. HTS then offered to let the SDF personnel leave the city. Yet the end results do not bode well for them—the SDF has reportedly withdrawn from Manbij and now faces attacks on Kobane to the northeast.

Meanwhile, ongoing HTS advances have left the group sharing a long frontier with the SDF. Given the jihadists’ goal of establishing a unified Syria under their extremist interpretation of Islamic law, HTS is unlikely to accept the continued existence of the secular SDF—at least not as a fully autonomous equal. Thus far, HTS has signaled restraint toward the Kurds, affirming that they are an “integral part” of Syrian society and opening the possibility for a negotiated settlement. Yet it is difficult to envision the group signing an agreement that does not disband the SDF or relegate it to a subordinate status. Absent a settlement, they might enter armed conflict; indeed, HTS may feel extra pressure to expand into SDF territory if the SNA keeps gaining ground, potentially sparking a scramble for territory in the northeast.

In that scenario, the jihadists would pose a serious military challenge to the SDF. HTS has invested substantially in improving its military capabilities over the past few years and displayed enhanced professionalism and innovative tactics during its offensive against Assad, including the proficient use of drones for command and control, surveillance, targeting, and antiarmor attacks. The Kurds have not faced such a determined jihadist adversary since the 2014-19 war against IS—in fact, without U.S. intervention in Kobane a decade ago, their forces might have been completely destroyed.

The SDF seems well aware of this danger today, recently noting the threat of IS expansion post-Assad. Months prior to the regime’s fall, U.S. Central Command noted a marked increase in IS attacks and warned that the group was “attempting to reconstitute.” IS forces had exerted partial territorial control in some areas by regularly assaulting pro-regime forces and extorting local populations. Now that Assad is gone, they are threatening to seize fuller control in the Badia.

As noted above, IS also hopes to break its fighters and families out of prisons and detention camps currently under SDF control in the northeast. Its 2022 attack on al-Sinaa Prison in Hasaka showed that it could still execute large operations, requiring the U.S.-led coalition to help the SDF stave off the assault. With 50,000 IS-affiliated individuals currently detained, a major SDF breakdown and IS breakout would be a disaster.

Policy Implications

Given that the SDF is America’s only reliable and capable counterterrorism partner in Syria, Washington will need to help the group halt SNA advances, deter HTS, and keep IS down. In the northwest, the U.S. priority should be to keep the SNA from moving further into SDF territory. Turkey and its proxies have faced allegations of abuse against Kurdish populations, and Washington has previously sanctioned SNA figures for such crimes. Moreover, neither Turkey nor the SNA has played a major role in combating IS in Syria. Once a major IS logistical hub, Manbij will likely be more vulnerable to jihadist exploitation in SNA hands.

In response to these developments, the Biden administration should make clear to Turkey—publicly and privately—that further SNA attacks are unacceptable and that the United States will provide air support to the SDF against them. Immediately extending bomber overflights to the area would signal resolve on this matter. Washington should also consider placing additional sanctions on SNA leaders, moving U.S. troops to the frontlines in Raqqa and Kobane, and extending joint patrols with the SDF. Heightened U.S. support would have the crucial side benefit of ensuring that the SDF does not overextend itself and neglect its duty to secure IS detention facilities.

At the same time, the administration must keep an eye on HTS, which could try to grab SDF holdings if it senses weakness—a scenario that would further jeopardize the fight against IS. Although HTS forces have cracked down on IS in Idlib, senior members of the global terrorist organization (including at least two of its former leaders) have previously found refuge in HTS territory. HTS also remains a U.S.-designated terrorist organization due to its former al-Qaeda ties and continued extremist tendencies. To acknowledge these risks and keep the counter-IS mission in Syria from falling apart, Washington should take the following urgent steps:

- Vehemently oppose HTS efforts to expand into SDF territory, making clear that the United States will resolutely support the SDF in the event of a major attack.

- Continue U.S. strikes against IS. “Dozens” of airstrikes on IS “camps” in central Syria have already been announced since Assad’s fall, and they should continue as needed. Sustaining the counter-IS mission will also necessitate a commitment to maintain the U.S. military presence in Syria (900 troops at present).

- Ensure the SDF’s readiness for territorial defense against potential jihadist threats, which will require more than the routine counterterrorism operations the group has conducted with coalition support in recent years.

Ido Levy is an associate fellow with The Washington Institute’s Military and Security Studies Program and a PhD student at American University’s School of International Service.