- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3989

Trump’s Foreign Assistance Review Prioritizes Funding Over Policy

Cutting aid programs is not inherently wrong—but making those cuts before assessing their specific impact on regional allies and American lives could be disastrous for U.S. policy in the Middle East.

Just two weeks into its new term, the Trump administration has initiated the most far-reaching overhaul of U.S. foreign assistance in decades. The proposed funding and staff cuts will have major implications around the globe, including for U.S. investments in Middle East stability.

An Immediate Mandate for Change

In one of his first executive orders upon retaking office, Trump instituted a ninety-day pause on all foreign assistance until officials determine that each program is “fully aligned with the foreign policy of the President of the United States.” Secretary of State Marco Rubio then clarified that aid programs must make America safer, stronger, and more prosperous—or else. For example, after being appointed acting administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development on February 3, Rubio placed most of its domestic and overseas staff on administrative leave. The agency’s future is now in question, not just its funding levels.

Trump’s EO does allow Rubio to waive the ninety-day pause for certain programs. Initially, military assistance to Israel and Egypt was exempted, as was food assistance worldwide. On January 28, Rubio issued another waiver for “life-saving humanitarian assistance,” leaving aid managers and local partners to question which activities meet this threshold. Among other potentially damaging effects, eliminating assistance would deprive the administration of a vital tool for advancing U.S. interests, including in its forthcoming weighty decisions about Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and other Middle East locales.

The Numbers

In fiscal year 2022/23, the U.S. government reportedly spent $11 billion on military and economic assistance in the Middle East, mostly in the form of bilateral aid. The vast majority of the $5.5 billion in military assistance—formally categorized as Foreign Military Financing (FMF)—went to Israel and Egypt (not including supplemental funds for Israel). Most of the remainder supported the armed forces of Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon. Without FMF, U.S. partners would lose equipment, capabilities, and training needed to combat terrorist groups and other hostile actors in the region. FMF also creates jobs in the United States by facilitating the production of American-made equipment and preventing countries from turning to China or Russia for such purchases.

On the economic side, the government disbursed approximately $5.6 billion to support health, welfare, and other aid programs in the Middle East and North Africa in FY 2022/23. Some of these programs have been on autopilot for years, and they are the most likely to be cut. Yet eliminating this safety net could contribute to social destabilization inside U.S.-allied countries. Currently, the top Middle Eastern recipients of U.S. economic assistance are:

- Jordan: $1.3 billion

- Syria: $900 million

- Yemen: $833 million

- Lebanon: $454 million

- Iraq: $342 million

- Egypt: $224 million

- Morocco: $175 million

- Tunisia: $150 million

- West Bank and Gaza: $112 million

- Libya: $73 million

Algeria and the Gulf states receive minimal funds, mainly for participating in training programs.

The United States spends most of its economic aid on humanitarian assistance; the remainder is split among the following categories:

- Economic development: $1.1 billion

- Education and social services: $383.7 million

- Peace and security: $271.4 million

- Democracy, human rights, and governance: $264.9 million

- Health: $224.6 million

- Environment: $15.15 million

- Multi-sector: $12.85 million

All of these programs are now vulnerable to extra scrutiny if not total elimination. The $270 million spent on supporting and managing assistance programs is particularly at risk. Democracy, health, and environmental funds will likely face the chopping block as well, in some cases because they contradict the administration’s stated domestic policies, and in other cases to encourage global burden sharing. In contrast, peace and security funds—which include programs related to counterterrorism cooperation, preventing weapons of mass destruction, and law enforcement training—have the greatest chance of surviving.

The cuts could also affect Washington’s willingness and capacity to provide emergency aid in urgent relief situations. In September, the previous administration announced $535 million in additional humanitarian assistance for Syria and $336 million for the West Bank and Gaza (on top of the $404 million the latter two territories received in June). And in May, $220 million in additional humanitarian aid was approved for Yemen.

Spending is only part of the story, however. The administration needs to answer fundamental policy questions about several countries before it decides to unfreeze, amend, or eliminate assistance.

Lebanon

U.S. support for the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) became increasingly controversial over the past two decades due to the army’s complicity in Hezbollah’s de facto takeover of the country. Now that Hezbollah has been decimated militarily by Israel, however, it is crucial to maintain—or, better yet, increase—the approximately $130 million that the LAF receives from the United States. Otherwise, the army will have great difficulty maintaining force readiness and motivation as it takes on formidable new missions, from fully implementing the ceasefire with Israel to disarming Hezbollah nationwide.

In light of the LAF’s role in meeting a vital U.S. national security goal, Secretary Rubio should immediately grant a waiver to keep assistance flowing to the force. This would help reassure LAF personnel that they will not be left out in the cold just as Washington and its partners are asking them to take on the dangerous and politically fraught task of confronting Hezbollah.

Iraq and Syria

The U.S. government has demonstrated a long-term interest in supporting the Iraqi security forces, investing $1.25 billion to improve their capabilities since 2015. In FY 2022/23, Baghdad received $250 million in military assistance. Pausing that support now will only increase the local risks to U.S. interests and personnel, particularly from Iran-backed militias that remain an impediment to regional stability and have vocally denigrated and threatened the Trump administration.

In Syria, Washington should be developing a new approach to assist the country during its dramatic transition away from the Assad era, not looking to cut aid. The United States has a clear national security interest in providing urgent, reasonably conditioned governance assistance to Syria’s new leaders and other local actors as they seek to form a stable arrangement among the country’s factions. Perhaps most important, all services to the al-Hol detention facility should be restored in order to limit the Islamic State’s influence over the camp’s thousands of residents, many of whom are affiliated with or sympathetic to the group. Yet other humanitarian aid will almost certainly be eliminated, such as funds for addressing gender-based violence. (Trump also reportedly wants to remove U.S. forces from eastern Syria, where their mission has been instrumental in keeping IS at bay—a separate but crucial issue that will be discussed in a future PolicyWatch.)

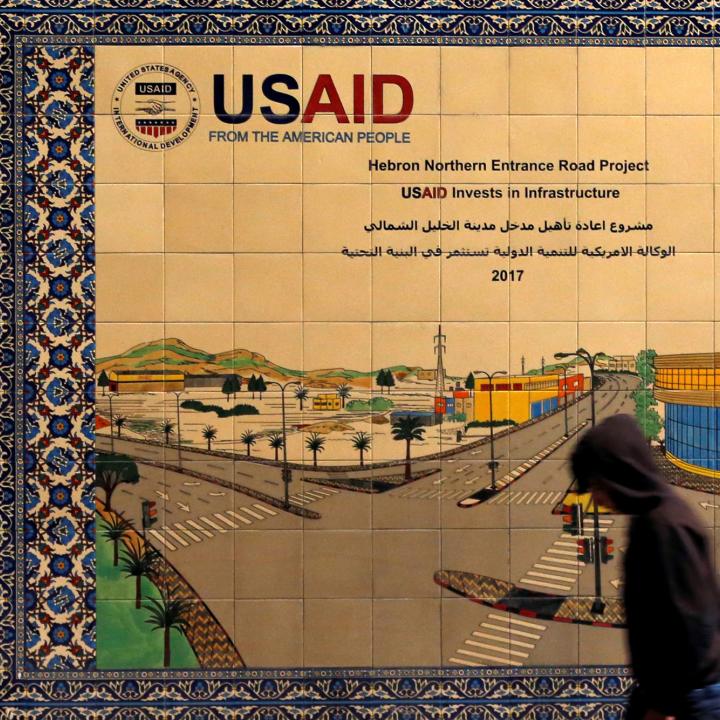

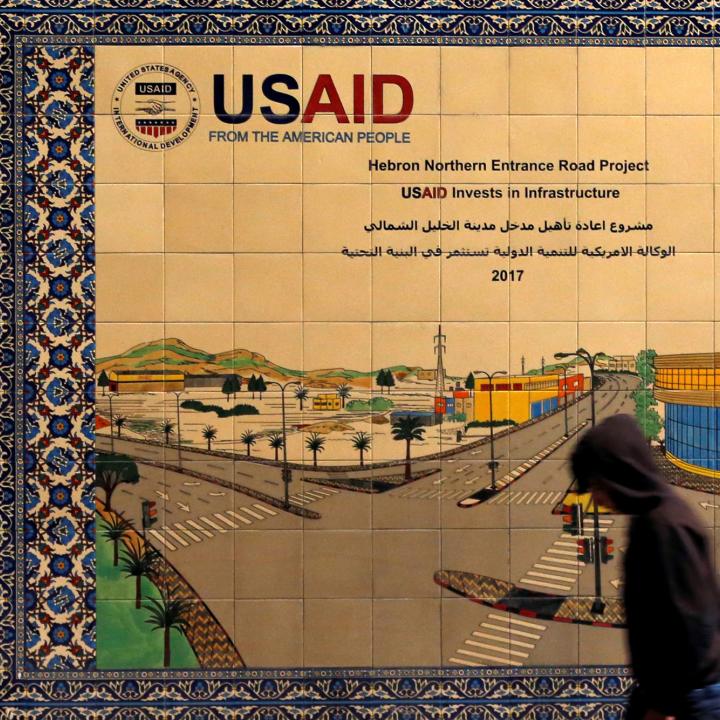

West Bank and Gaza Strip

Aid to the Palestinians will be more heavily scrutinized than ever due to the Gaza war. The 2018 Taylor Force Act already prohibits direct U.S. assistance to the Palestinian Authority until it stops paying violent prisoners and the families of terrorist “martyrs.” Yet the Israeli security establishment favors supporting PA security forces in the West Bank because they reduce the need for certain Israeli operations. The strategic question of who will secure and govern postwar Gaza also looms large, and any new decisions about aid could affect the PA’s ability to reenter the Strip as a potential replacement for Hamas.

Of course, the current Israeli government has repeatedly stated that it does not want the PA to return to Gaza, and President Trump’s latest announcement about potentially depopulating the Strip further complicates the picture. Yet withholding assistance from the PA security forces amid growing unrest in the West Bank would be dangerous. Instead, funding decisions should be postponed until President Trump’s Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff has time to negotiate the future of Gaza.

Jordan

The stability of Jordan is central to both the stability of the Middle East and the security of Israel. King Abdullah II will have a good opportunity to deliver that message directly to Trump when they hold talks at the White House on February 11—the president’s first meeting with an Arab leader during his new term. But the king cannot take the historically strong bilateral relationship as a given. Jordan relies heavily on U.S. support of its economy and military, receiving around $780 million annually in direct budget support. No other country in the world except Ukraine receives this type of support.

During Trump’s first term, he balked at the price tag of assistance to Jordan but ultimately decided not to cut it. The new aid freeze may indicate he is reconsidering that decision. Moreover, he has publicly challenged the kingdom’s political identity by suggesting that Jordan (and Egypt) receive refugees from Gaza—a potentially existential issue for Amman. If Trump threatens to cut Jordan’s aid during or after the king’s visit, it will create a rift in the relationship, with uncertain implications for Amman’s ability (let alone willingness) to admit more refugees.

Indeed, policy should be determining U.S. assistance levels, not the other way around. Whatever the president decides, acknowledging Jordan’s centrality to regional stability is the first step in forging a policy of his own.

Conclusion

The Trump administration chose to take a big swing at the aid establishment before making major policy decisions. As it proceeds with this review process, it will need to establish which issues and states it deems most crucial to the United States, and therefore most worthy of U.S. support. This entails setting specific guidelines to define what a “safer, stronger, and more prosperous” foreign policy means in practical terms, at least for strategic issues. The review can then work backwards to determine which existing programs contribute most to U.S. security, stability, and prosperity, and which can be safely eliminated without putting allies or Americans at risk.

Ben Fishman is the Levy Senior Fellow in The Washington Institute’s Rubin Program on Arab Politics.