In light of Emirati complaints about the Qatari air force intercepting civilian airliners, Washington should caution both sides in the ongoing Gulf dispute.

After several months of relative quiet, Qatar's row with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Egypt has heated up again due to a quick-fire series of developments:

- On January 11, the Qatar News Agency reported that Doha had complained to the United Nations about a UAE fighter briefly intruding into its airspace on December 21.

- On January 13, Qatar asserted that a UAE military transport had flown through its airspace on January 3 en route to Bahrain.

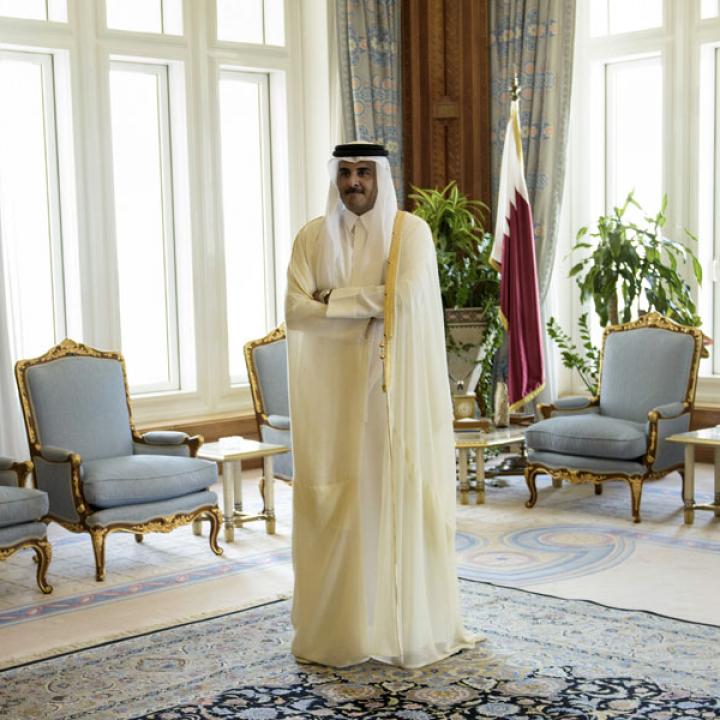

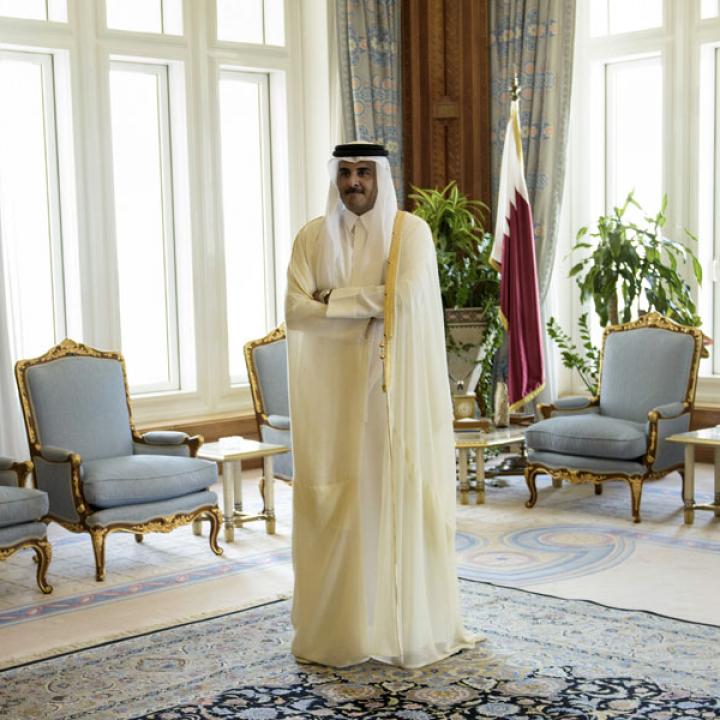

- On January 14, marginal Qatari sheikh Abdullah bin Ali al-Thani alleged that he was being held against his will in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the UAE. Last August, he had met with Saudi leaders in a move that was interpreted as Riyadh labeling him their preferred replacement for Qatar's ruler, Emir Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani. Doha condemned his action, spurring him into exile in the UAE.

- On January 15, the Emirates News Agency reported that Abu Dhabi had complained to the UN after two Emirati airliners were approached by Qatari fighters while preparing to land in Bahrain.

- On January 17, the exiled Sheikh Abdullah reportedly flew to Kuwait for a medical checkup in a military hospital, belying his claim that he could not leave the UAE.

The original diplomatic crisis erupted in May 2017 when hackers allegedly used the Qatar News Agency and other state outlets to transmit a false report quoting Emir Hamad as saying, "There is no reason behind Arabs' hostility to Iran." Ignoring Qatari denials of the quote, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt formally broke off diplomatic relations with Doha two weeks later, instituted an economic blockade, and banned Qatari civilian aircraft from their airspace. They then announced a list of thirteen demands as a precondition for renewing relations; the list included curbing terrorist financing, ceasing hostile broadcasts by Qatar's Al Jazeera television network, and reducing links with Iran.

In July, the Washington Post reported that the UAE had orchestrated the May hacking attack, but the diplomatic row continued. Although the Emirati ambassador in Washington, Yousef Al Otaiba, described the Post report as "false," its key findings were attributed to unnamed U.S. intelligence officials, and its accuracy has since been acknowledged by diplomats the length of the Gulf.

UNCONSTRUCTIVE AMBIGUITY

The latest incidents are partly a consequence of the Gulf's uncertain air traffic arrangements. Civilian traffic flying east along the southern Gulf coast is controlled first by Bahrain and then handed over to the UAE. Qatar is not involved, so its airliners have had to fly north into the Iranian-controlled zone ever since Bahraini and Emirati controllers were barred from handling them. Meanwhile, Bahraini and Emirati civilian planes continue to transit Qatar's airspace (in September, the author watched the route screen as his flight on the Bahraini flag carrier Gulf Air flew over northern Qatar en route to Abu Dhabi; info on the website flightaware.com confirms these and other peculiarities regarding Gulf routes).

The embargo on Qatar is ambiguous in other ways too; three days ago, for instance, the author was able to buy Qatari riyal at the money exchange in Abu Dhabi airport. Even so, the intensity of the Gulf schism should not be underestimated. In the children's section of Abu Dhabi's new flagship Louvre Museum, a map of the southern Gulf completely omits the Qatari peninsula—a geographical deletion that is probably incompatible with France's agreement to let Abu Dhabi use the Louvre's name.

Regarding the danger of military escalation, Qatar likely has no real interest in that scenario. Saudi Arabia has closed the country's only land border, so Doha realizes that it is now essentially an island with no reliable means of providing for its needs indefinitely. Iran has provided an alternative route for food imports, but any cooperation with Tehran beyond this cannot be guaranteed. As one local diplomat put it, Qatari-Iranian political links are "imperceptible."

UAE TAKING THE LEAD?

Many regional diplomats believe the crisis is being driven not by the Saudis, but by de facto Emirati leader Crown Prince Muhammad bin Zayed. According to the UAE, the Qatari emir's father, Hamad, continues to play a key role in the country's decisionmaking despite abdicating in 2013. Yet local diplomats reject this notion completely, saying they no longer keep track of the so-called "Father-Emir."

As for the widely held assumption that the crisis would continue simmering rather than boiling over, the latest escalation—whether real or rhetorical—may be the UAE's way of reasserting its narrative after the embarrassment over the exiled Qatari sheikh. In November, former Egyptian prime minister Ahmed Shafiq similarly accused Abu Dhabi of holding him against his will after living in exile there for some time, so Emirati sensitivities about such matters were already piqued.

U.S. RESPONSE

The situation is a predicament for the United States, which almost certainly knows what happened in the airspace incidents even if it has so far declined to opine publicly. The Combined Air Operations Center at Qatar's al-Udeid Air Base has a huge screen capable of showing all air traffic from southern Iraq to Afghanistan, and the 10,000 U.S. military personnel posted in the peninsula no doubt have other technical capabilities that allow them to monitor all military takeoffs and landings in the area. The UAE alleges that the Qatari fighters involved in the recent airliner incident took off from al-Udeid.

On January 15, the White House announced that President Trump had spoken with Qatar's emir by phone and thanked him for Doha's efforts "to counter terrorism and extremism in all forms, including being one of the few countries to move forward on a bilateral memorandum of understanding." There has been no report of an equivalent White House conversation with UAE leaders—hardly surprising given Washington's apparent frustration with their unwillingness to resolve the Gulf crisis. For their part, the Emiratis may be irritated by the warm tone of the president's statement on Qatar. Whatever the case, Washington needs to be fully aware of the personal aspects behind the crisis, including intense animosity that may require careful handling to avoid further escalation.

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Gulf and Energy Policy Program at The Washington Institute. He has just returned from a research trip to the UAE, Oman, and Qatar.