- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3924

The U.S.-Morocco FTA After Twenty Years

The agreement has not led to the expected levels of economic growth, but Washington can still use it to bolster the bilateral relationship, encourage reform, and open up other markets in Africa.

In August 2004, President George W. Bush signed the implementing legislation of the U.S.-Morocco Free Trade Agreement (MAFTA), a comprehensive deal meant to improve bilateral commercial relations by reducing and eliminating trade barriers. Today, Morocco remains one of only a handful of countries with such an agreement, and the only one in Africa. What results have the two partners seen after two decades under this privileged arrangement?

Persistent Trade Imbalance

Conceived in the wake of 9/11, the MAFTA was motivated by both strategic and economic interests. In addition to rewarding Morocco for its counterterrorism cooperation and efforts to promote tolerance, the Bush administration aimed to advance the U.S. vision of a larger “Middle East Free Trade Area,” while Rabat was keen to deepen the bilateral relationship, including its security component. Upon signing the agreement, Washington also announced significantly enhanced bilateral assistance and granted the kingdom “major non-NATO ally” status.

On the economic side, although Moroccan goods and services comprised a relatively small share of U.S. imports, American producers welcomed wider access to Moroccan markets—particularly in sectors like agriculture, where reduced tariffs would give them an edge over foreign competitors. Similarly, Morocco welcomed the opportunity to diversify its trading partners, integrate into global markets, and reduce its dependence on Europe.

The resultant benefits of the deal are easily quantifiable—since the MAFTA was implemented, total bilateral trade has more than quadrupled, from roughly $1.3 billion in 2006 to $5.5 billion in 2023. Among the top Moroccan exports to the United States today are fertilizers, semiconductor devices, and motor vehicles, while the kingdom’s top U.S. imports include fuels, aircraft parts, and gas turbines.

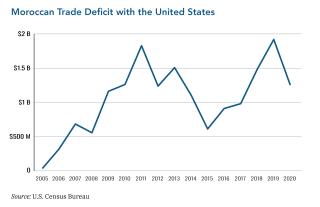

Yet a persistent—even growing—trade imbalance indicates that the MAFTA’s full economic potential is not being fully realized. In 2006, Morocco’s trade deficit with the United States was less than $1 billion; by 2023, it had increased to around $1.8 billion.

To be sure, the kingdom has experienced significant economic growth over the past two decades, with real GDP rising from roughly $63 billion in 2005 to almost $131 billion in 2022. Yet such achievements appear to stem mostly from factors unrelated to the MAFTA. For instance, Morocco’s real GDP growth reached 5.15% in 2010 despite the global financial crisis at the time, likely due to good rainfall fueling its agricultural sector. Yet by 2022, growth had fallen to 3.68%, in part because of prolonged drought. Moreover, during the COVID-19 crisis, many international investors looking for ways to shorten global supply chains took advantage of Morocco’s proximity to Europe and Africa. The kingdom’s domestic policies—including an updated investment charter and key infrastructure projects such as a high-speed rail line and massive Mediterranean port—also played more of a role in enhancing its stature as a “nearshoring” destination.

The MAFTA has not produced the expected growth in traditional Moroccan exports either, including textiles. When the Multifiber Arrangement—which had gradually dismantled the World Trade Organization’s past quota system governing textiles—ended in 2005, it phased out protections on Morocco’s industry at the same time that the MAFTA was gearing up for implementation. In anticipation of this shift, Moroccan producers had reoriented themselves toward European markets by favoring the production of finished products with a short turnaround time. Stronger existing European trade ties also encouraged them to cater to continental preferences, while the “Rules of Origin” requirements established by the MAFTA created a hurdle for exporters looking to enter the U.S. market. In 2021, textiles comprised roughly 12% of Moroccan exports to the United States, a relatively small increase from the 8% seen in 2008 (in comparison, fertilizer exports grew from 7% to 23% during the same period). This growth remained modest despite the kingdom receiving major concessions during MAFTA negotiations concerning textiles (thanks to the strong representation of textile producers in Moroccan civil society).

Meanwhile, two of Washington’s other close regional partners, Egypt and Jordan, have seen their export sectors grow thanks to the establishment of Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZ), which provide reduced tariffs for goods co-produced with Israel. Morocco officially normalized relations with Israel in 2020 and has reportedly pushed for a QIZ of its own to help increase textile exports to the United States. Yet such a zone would not make as much sense geographically as it does for Egypt and Jordan. Language differences have also been cited as a barrier to deepening U.S.-Moroccan trade, particularly in the service sector (here too, Europe has a built-in advantage).

Investment Potential?

To realize its potential as a key global supply node, the kingdom has specialized in niche markets such as electric vehicle (EV) batteries, which use critical minerals found largely in China but also in Morocco and certain other African countries. In theory, the MAFTA should stimulate investment in this sector, including from third parties eager to take advantage of access to American markets. Moreover, Washington’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) incentivizes U.S. investors to fund carbon-reducing industries like EV batteries, especially with countries that have signed bilateral free trade agreements.

Yet Morocco has also welcomed investments from China, which is eager to take advantage of the kingdom’s stable macroeconomic environment and proximity to major markets. In May-June alone, three Chinese companies announced plans to open plants for producing EV batteries or components in Morocco. Indeed, the kingdom has seen a surge in announced “greenfield” investment, ranging from EV manufacturing to green hydrogen projects. China is leading this surge, while U.S. capital represents only 1% of such investment. The rapidly growing Chinese presence in Moroccan manufacturing of greenfield products may help explain Washington’s reluctance to encourage U.S. investors to follow suit—the Biden administration seeks to diversify the supply chains underpinning the IRA’s carbon-reduction objectives.

The MAFTA should also theoretically nudge Rabat toward internal reforms that would further open its markets and increase its economic growth. Yet the kingdom’s implementation of such measures has been mixed. In a 2016 review, the WTO praised Morocco’s “numerous reforms to its trade regime,” including its implementation of the Plan Maroc Vert (Green Morocco Plan), meant to reduce the trade deficit while promoting sustainable development. Yet other reforms have lagged. Concerns remain about the heavy state presence in key industries (e.g., phosphates), uneven access to credit, and corruption. Additionally, despite some improvements in human development indicators over the past several decades, Morocco’s literacy and employment rates remain relatively low (particularly for females), reflecting an education system that has not succeeded in preparing a high-skilled workforce or supporting a dynamic labor market.

In contrast, Morocco has positioned itself well to facilitate and benefit from economic growth and investment in Africa. By reaching bilateral trade agreements with numerous African partners and signing the African Continental Free Trade Agreement, the kingdom sought to reap benefits from enhanced foreign direct investment there—indeed, it is now one of the leading African countries in terms of FDI inflows. To the extent the United States is interested in promoting economic growth and trade with Africa—including as an alternative supplier of critical minerals—investing in Morocco is one way to go.

Policy Recommendations

On balance, the MAFTA appears to have served political and strategic interests more than economic ones. Given the strategic sectors Morocco has chosen to develop, the agreement may never truly fulfill its potential, and renegotiating it to better target persistent bilateral economic issues is unlikely given Washington’s rise in protectionist attitudes.

Even so, the MAFTA has helped maintain a robust bilateral relationship amid shifts in U.S. politics. Most prominently, the Biden administration chose not to reverse the Trump administration’s 2020 decision to recognize Morocco’s claim to sovereignty over the disputed Western Sahara territory—a position that is now the anchor of bilateral ties. Regardless of who wins the U.S. election in November, the next administration is unlikely to move backward on this issue, especially now that France has also recognized Rabat’s claim. Meanwhile, U.S. assistance programs continue to support trade-related sectors such as agribusiness and inclusive growth.

Going forward, the United States should use trade to support Morocco’s economic growth by focusing on industries such as light manufacturing, which can help generate new jobs, especially for women. Washington should also continue working through the International Development Finance Corporation to identify initiatives that both enhance U.S. investment and prompt Morocco to implement environmental and labor reforms. Finally, given the kingdom’s past decision to bolster English-language instruction, Washington and other Anglophone countries should expand language training opportunities with Morocco for their mutual economic benefit.

Sabina Henneberg is a Soref Fellow at The Washington Institute.