- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3136

East Mediterranean Energy and Middle East Peace

The slow but steady progress in developing offshore gas fields is transforming local economies and could underpin U.S. peace plans.

Last week, after a year of negotiations, the government of Cyprus and a consortium led by Texas-based Noble Energy announced agreement on a revised contract to exploit the Aphrodite natural gas field 100 miles south of the island. Development of the field, which partly lies in Israel’s exclusive economic zone, will cost several billion dollars, and the first gas will flow in 2024 at the earliest, probably to Egypt for export to the rest of the world. Total revenues over the field’s projected twenty-year lifespan are estimated at more than $9 billion. The next step in the deal—formal approval by the Cypriot cabinet—seems like a foregone conclusion, but as is so often the case, any energy developments in the East Mediterranean have wider geopolitical angles.

The Israeli claim on Aphrodite can be settled by arbitration, but a much more difficult issue reared its head on June 7, when Turkey announced that Cypriots living in the island’s Turkish-occupied northern zone had rights to a share of the field. The internationally recognized government in Nicosia—which asserts sovereignty over the entire island and grants passports to Turkish Cypriots—has previously acknowledged in principle that Aphrodite’s eventual revenues will be for all Cypriots. However, this principle is complicated by the large number of Turkish settlers on the island, many of whom lack the proven Cypriot heritage required to receive passports and certain other rights. Ankara’s latest statement therefore exacerbates fears that the Turkish navy will harass international exploration and development efforts in contested waters.

Meanwhile, gas supplies that generate two-thirds of Israel’s electricity were stopped briefly last month out of concern that Hamas rocket fire from Gaza might endanger an offshore processing platform. Such incidents are part of the reason why Israel’s second platform—currently being built to serve the about-to-produce Leviathan field—is located much further north and closer to shore, where it can be better protected.

On the positive side, Israel has been using small quantities of gas to test a dormant pipeline on the seabed between Ashkelon and the Sinai city of al-Arish. The line was previously used to pump Egyptian gas to Israel, but it has now been reversed and will soon transport gas from Israel’s offshore fields to Egypt—whether for domestic use or for export once converted to liquefied natural gas at existing LNG plants near Port Said and Alexandria. Reaching final legal agreement on these proposals has been difficult, however, and even when gas flows in quantity beginning later this year, it will have to use a land route vulnerable to terrorist attack by al-Qaeda and Islamic State elements for part of its journey, at least until another expensive offshore pipe extending further west from al-Arish can be agreed and built.

Israel is also looking for companies that can explore its waters for more gas. Although a deadline for bids on nineteen offshore blocks has been pushed back to mid-August, perhaps reflecting a lack of investor interest, Israeli officials are reportedly still hopeful that ExxonMobil will bite. For now, the U.S. company has shown more interest in Cypriot blocks, as have European companies like Total of France and Eni of Italy.

The latter two companies are also interested in exploring Lebanon’s waters, despite the country’s dysfunctional government, broken electricity supply network, and intrusive Iranian influence. They hope to start drilling northwest of Beirut before the end of the year. More contentiously, their consortium, which includes a Russian company, wants to drill in another block that encompasses a sliver of sea contested by Israel. Under UN cover, U.S. diplomats have been encouraging both countries to reach agreement on at least some elements of their decades-long maritime and land border disputes, possibly signaling American corporate interest in exploring Lebanon’s waters.

When it comes to energy deals, however, even a peace treaty does not put an end to public sensitivities about rapprochement with Israel. For instance, Jordan’s security and intelligence links with Jerusalem have strengthened greatly since the two governments signed their treaty in 1994, and Israeli gas has powered Jordanian industrial plants on the Dead Sea for the past two years. Given the consistently poor people-to-people relations between the two nations, however, many Jordanians oppose the prospect of using Leviathan gas for large-scale electricity generation beginning early next year. Amman has partially deflected such anger by calling the supplies “northern gas” or “American gas,” emphasizing Noble’s role in producing it.

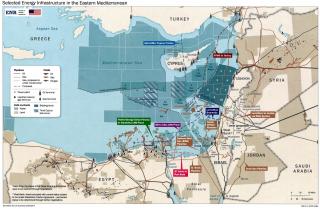

The complexities of East Mediterranean energy developments are well illustrated by the above map, declassified by the State Department’s Bureau of Energy Resources (ENR) and obtained by McClatchy. Some officials argue that the area’s underlying geology could help Europe offset or even replace its dependence on Russian gas, but this seems farfetched at the present level of discoveries. Several more giant fields like Leviathan or Egypt’s Zohr would have to be found before this reality changes. The proposed construction of a seabed pipeline to carry gas to Greece and Italy is similarly unrealistic at present. According to the latest BP Statistical Review of World Energy, Israel’s current discoveries amount to just 0.2 percent of global proven gas reserves. Egypt’s are more than five times greater, though still dwarfed by the reserves of the world’s top three producers: Russia (19.8 percent), Iran (16.2 percent), and Qatar (12.5 percent).

Even so, the role of gas is growing in the global economy: both consumption and production were up by over 5 percent in 2018, which BP described as “one of the strongest rates of growth for both demand and output for over thirty years.” And while pipeline delivery still dominates, LNG tankers account for an increasing share of exports. The United States will likely become the number three LNG exporter this year, after Australia and Qatar—another reminder that trends can change rapidly, since America was a significant LNG importer up until ten years ago.

Washington is also encouraging the new Cairo-based East Mediterranean Gas Forum to cooperate on energy projects, though Lebanon and Turkey are not yet included in the organization. Meanwhile, the ENR leads the energy pillar of the Middle East Strategic Alliance (MESA), the slow-moving, American-led project to advance regional stability.

Finally, gas cooperation will likely be on the agenda at the economic workshop Bahrain is hosting later this month to develop the Trump administration’s Israel-Palestinian peace efforts. Although the Palestinian Authority has stated it will not attend, increased energy integration that benefits the West Bank and Gaza seems like an obvious element for discussion, including exploration and joint electricity production. More specifically, the agenda in Bahrain should include:

- Building on current gas infrastructure joining Israel, Egypt, and Jordan

- Developing joint gas-fired power projects

- Cooperating on other power projects (e.g., solar)

- Integrating Palestinian assets into joint projects (e.g., exploiting the offshore Gaza Marine gas field; better utilizing the existing power station in Gaza, originally built for using gas).

Such efforts would reiterate the historical lesson of East Mediterranean gas development: that progress is slow but achievements are significant, and seemingly insurmountable obstacles can be overcome with patient, meticulous diplomatic effort.

Simon Henderson is the Baker Fellow and director of the Bernstein Program on Gulf and Energy Policy at The Washington Institute.