Given the dilemmas involved in retaliating for recent acts of sabotage and the death of Qasem Soleimani, Iran will likely defer any substantial military action against U.S. targets until shortly before or after the November election.

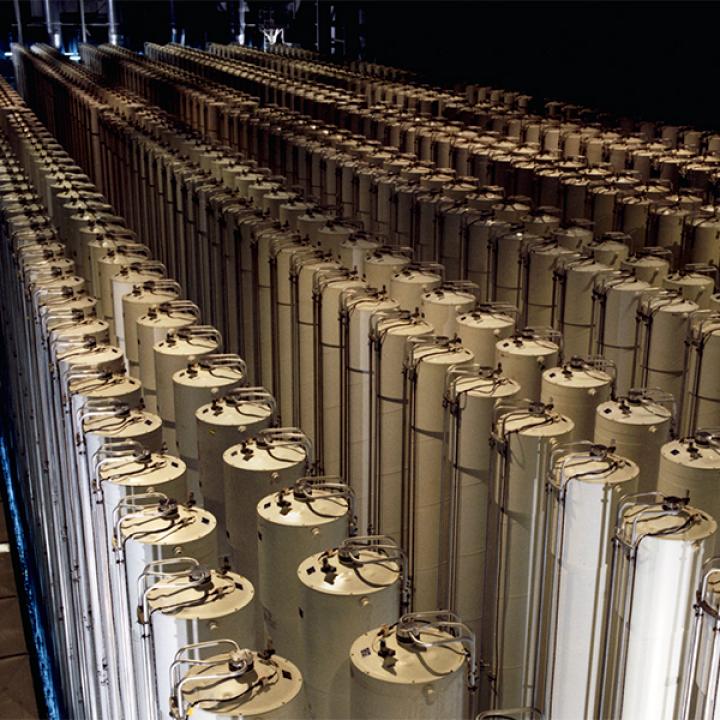

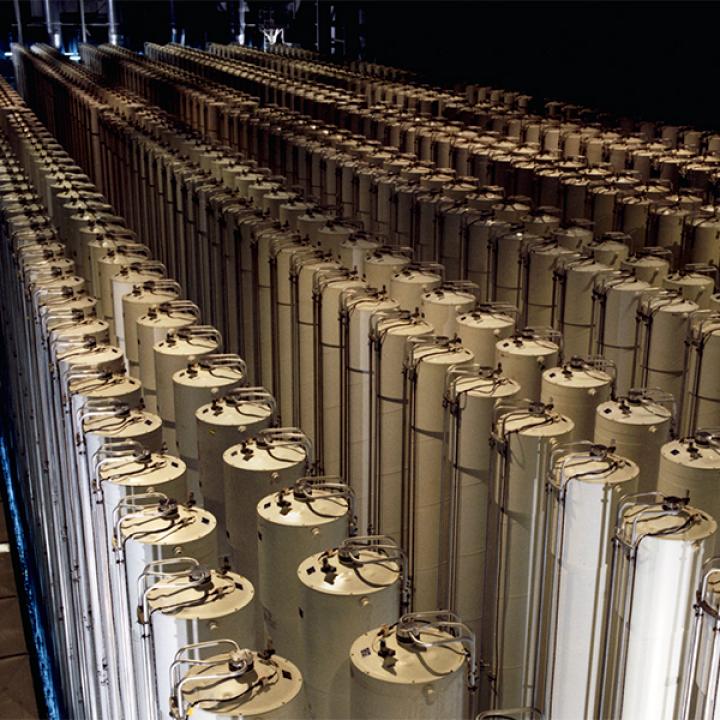

Iran has been hit by a series of fires and explosions at civilian and military industrial sites in recent weeks, including the Khojir missile research complex near Tehran and the county’s principal uranium enrichment facility at Natanz. Well-sourced U.S. and Israeli media reports suggest that Israel was responsible for the Natanz incident and that the United States may be involved in sabotage efforts as well, though many of these incidents appear to be accidents. Such events are quite common in Iran due to the country’s poor infrastructure and safety culture—indeed, around ninety-seven of them were documented in May-July 2019, while eighty-three or so occurred during the same period this year. Even so, Iran has threatened to retaliate for any acts of sabotage, though it has thus far avoided blaming Israel or the United States for these incidents. This begs the question of whether, how, and when it might act.

THE STRATEGIC LOGIC OF REPRISALS

Beset by economic ills that have been exacerbated by U.S. sanctions, popular unrest, and a pandemic, Iran would seem to be in no shape to respond militarily, whether for potential industrial sabotage or for the targeted killing of senior military commander Qasem Soleimani in January. (Just two weeks ago, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei warned on Twitter that Iran would eventually “strike a similar blow” against the United States as revenge for Soleimani’s death.) Yet there is no evidence that Tehran’s external activities are constrained by problems at home.

For example, not long after nationwide economic protests subsided in January 2018, Iran launched a drone attack on Israel from Syria. Similarly, after the regime quashed last November’s protests over increased fuel prices, it dramatically ramped up attacks on U.S. forces in Iraq. And despite suffering a coronavirus outbreak this February, the country renewed efforts in March-April to divert oil tankers and harass U.S. warships in the Persian Gulf, after a prolonged pause to such activities. These and other external operations do not seem intended to divert attention from internal difficulties either, so what factors determine their scope and timing?

DIFFERING CALCULUS TOWARD ISRAEL AND THE UNITED STATES

When contemplating its response options, Tehran often treats Israel differently from the United States. Despite Israel’s impressive capabilities, the so-called “Little Satan” is a small, regional power that Iran does not consider its equal, and against which it has waged a decades-long shadow war. In recent years, Israel has taken a more proactive approach to dealing with emerging threats from the Islamic Republic, conducting hundreds of interdiction operations and spoiling attacks in Syria as part of its “campaign between the wars,” most of them geared toward preventing Iran from transferring advanced arms to Lebanese Hezbollah or transforming Syria into a springboard for attacks on Israeli soil.

If Iran ultimately attributes any recent acts of sabotage to Israel, it will almost certainly respond as it has in the past: with cyberattacks against Israeli critical infrastructure and rocket, drone, or missile attacks from Syria. In addition, reports indicate that the Mossad recently thwarted several planned attacks on Israeli embassies in Europe and elsewhere. If true, this would be an unusually severe response to an act of nonlethal sabotage, so these reports should be treated with caution. Iran last attacked Israeli embassies in 2012 after the killing of several nuclear scientists.

Iranian actions against the “Great Satan” reflect a more complex calculus given America’s status as a great power with a military presence along Iran’s borders. Since May 2019, Tehran has been waging a campaign to counter the U.S. policy of “maximum pressure,” with the aim of forcing Washington to ease or lift sanctions. This includes attacks on oil infrastructure and transport in the Gulf and Saudi Arabia; the diversion of oil tankers; attacks on U.S. reconnaissance drones; nonlethal and lethal rocket attacks on U.S. military personnel in Iraq; harassment of U.S. naval vessels in the Gulf; and cyber reconnaissance activities, perhaps in preparation for interfering in the 2020 presidential election or sabotaging U.S. infrastructure.

Thus far, this pushback has contributed to tensions between Washington and its allies, but without achieving the goal of sanctions relief. Moreover, Tehran still appears to be recovering from the shock of Soleimani’s death. The regime’s response to both his killing and any U.S. involvement in recent sabotage will be influenced by several factors:

One “Satan” at a time. Tehran may believe that the United States and Israel cooperated on the latest incidents at Natanz and elsewhere, just as they cooperated in the Stuxnet cyberattacks on Natanz beginning in 2007. Generally, however, the regime has been reluctant to escalate simultaneously against both enemies. And whenever it deems U.S. interests as too difficult or dangerous to target, it tends to lash out at Israel and/or Saudi Arabia instead. In 2010, for example, it warned Washington and Jerusalem that they would both be held responsible for killing Iranian nuclear scientists, though U.S. officials denied involvement at the time; in the end, it targeted only Israeli interests.

Strategy before revenge. Although Iranian leaders often pepper their pronouncements with threats of revenge, their behavior generally reflects strategic considerations. And because they tend to see the world in zero-sum terms, they believe that if they do not respond to perceived transgressions, they risk emboldening their enemies.

To limit the potential for escalation, however, they generally limit these responses to in-kind, proportional, and covert/proxy actions. And if it is in their interest to defer a response, they may do so—perhaps indefinitely. Indeed, their entire “gray zone” strategy is intended to manage risk and prevent war. That is why Iran gave Baghdad advance warning of the missile attacks it launched at Iraqi bases in response to Soleimani’s killing, knowing that U.S. military personnel would receive word in time to adopt protective measures. Headlines claiming that America and Iran were on the “brink of war” in January are not grounded in reality.

Yet even as the desire to avenge Soleimani takes a backseat to strategy, Iran’s precision drone and missile strike on Saudi oil infrastructure last September demonstrated that it possesses some of the capabilities needed for a targeted strike on senior U.S. military officers, even though it may be unwilling to risk a move of that magnitude at present. Such an attack would most likely occur in Iraq—the scene of the “crime” and an arena in which Tehran has particularly good intelligence.

Avoiding a second Trump term. Another major factor for Iranian decisionmakers is the potential impact that retaliatory action might have on President Trump’s prospects for reelection—an outcome they almost certainly want to avoid. They are probably considering how best to scuttle his chances for a second term, but they face a series of dilemmas in doing so.

For example, they will likely continue their counter-pressure campaign, including harassment attacks on U.S. personnel in Iraq. Yet a dramatic attack before the November election might backfire—it could cause Trump to strike back forcefully and give him a bump at the polls. Alternatively, Iranian leaders might wait until after the election to strike, reasoning that if he loses, his lame-duck administration will have limited response options, and they will then be able to engage the new administration from a position of strength. If he is reelected, however, they would have to choose between two fraught paths: engage in military brinkmanship in order to foment a crisis, catalyze diplomacy, and negotiate a comprehensive deal with Washington, or take a more cautious approach with a president who may no longer be constrained by electoral considerations.

CONCLUSION

Tehran’s counter-pressure campaign has neither delivered sanctions relief nor led to renewed negotiations with Washington, and there is little chance of reaching a new deal with the election less than four months away. Thus, the regime will likely continue with elements of this campaign to show that it is not bowed, yet defer any major action it may be planning against U.S. targets until shortly before or after election day. To further encourage Iranian restraint, Washington should demonstrate continued readiness to respond militarily to attacks while eschewing measures that push Tehran deeper into a corner.

Michael Eisenstadt is the Kahn Fellow and director of the Military and Security Studies Program at The Washington Institute.