- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3670

Iran’s Nuclear Roadmap for 2019: Pushing the JCPOA’s Boundaries

As Tehran’s economic patience grows thinner, it may try to exploit holes in the nuclear deal as a way of pressuring the West, but this strategy could prove to be a double-edged sword.

Three years have passed since implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), yet the fruits of the nuclear deal have not lived up to Iran’s lofty expectations. Hence, Tehran’s dilemma has intensified: should it escalate the situation and retaliate harshly against U.S. pressure, or restrain itself to prevent the emergence of a united Western coalition against Iran? And is the latter approach sustainable when it has brought only limited economic compensation from Europe so far?

Earlier this month, Supreme National Security Council secretary Ali Shamkhani hinted that Iran’s patience on these matters is wearing thin, and that Europe’s opportunity “has ended.” Yet the regime has seemingly eschewed blunt escalation in favor of a middle way—deterring the West without breaking the deal. On January 22, Ali Akbar Salehi, director of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), defended the decision to stay in the deal but also listed various nuclear steps the regime is taking to send “the necessary message.” He emphasized that these activities are possible because “the nuclear talks have left so many breaches in the agreement for Iran to exploit,” much as it has done with other international agreements and norms.

IRAN’S NEXT NUCLEAR MANEUVERS

The JCPOA is a 159-page document that lays out a complex network of restrictions with numerous loopholes and technical ambiguities. Given Tehran’s track record of exploiting such lacunae, foreign governments can expect the regime to take the following steps toward strengthening its leverage.

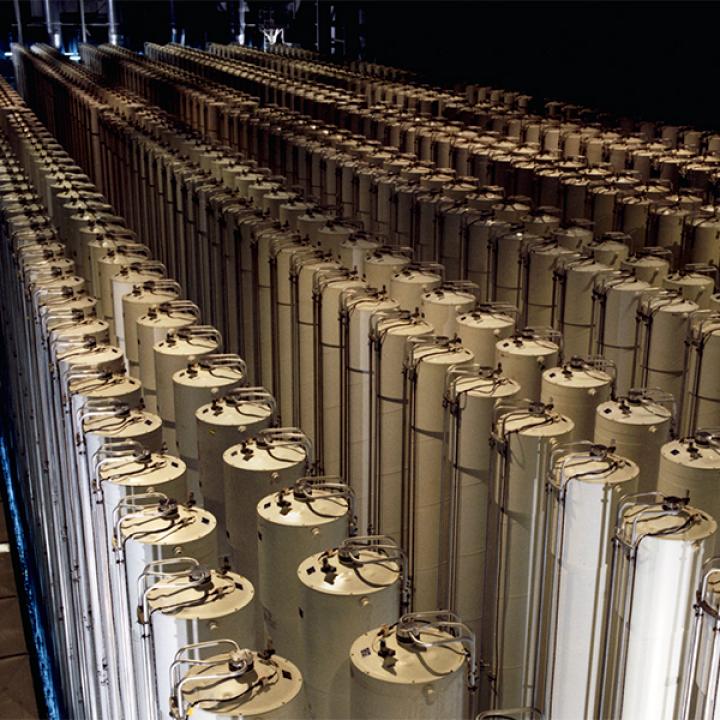

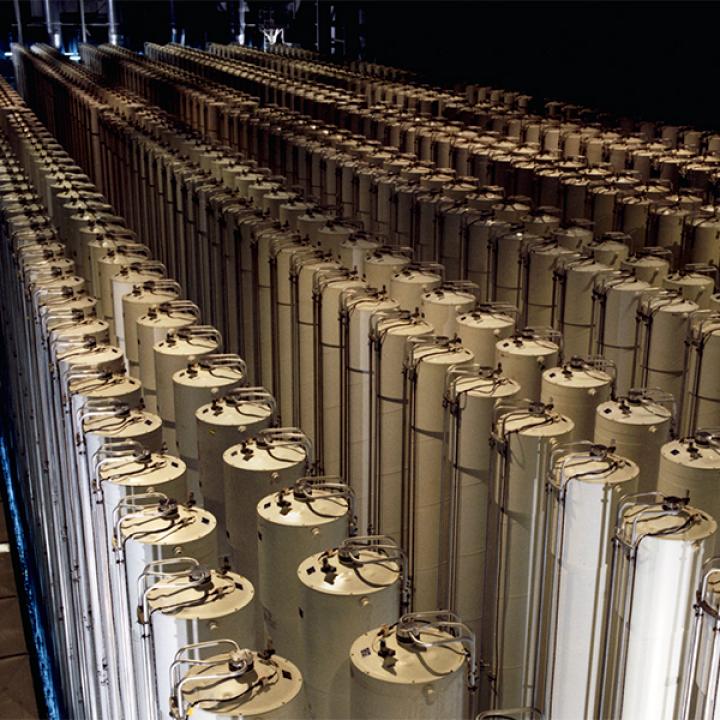

Emphasizing its need for 20 percent enriched reactor fuel. Enriching uranium so that it contains 20 percent of the fissile isotope U-235 is a crucial milestone in attaining the high-enriched uranium (HEU) needed for nuclear weapons. Iran also uses 20 percent uranium to fuel the Tehran Research Reactor, where it produces medical isotopes—one of the prides of the country’s civilian nuclear program.

Under the JCPOA, Iran is currently proscribed from enriching to 20 percent and had to export its existing stock of such uranium to Russia. Yet the deal also allows the regime to import small quantities of it under international inspections in order to produce fuel pellets. Tehran may hope to justify a future JCPOA breach by declaring that current sanctions prevent it from obtaining this material, claiming it needs to produce 20 percent uranium on its own to meet its needs.

Recently, Salehi used intentionally vague language to announce that Iran is “working on” an upgraded design for its reactor fuel. He also implied that while the regime does not need to enrich to 20 percent for the time being, it may choose to store uranium at this level if necessary.

Advancing its naval nuclear propulsion project. Since 2012, Tehran has suggested that it may need to produce nuclear-fueled ships and submarines because sanctions have forced its navy to look for alternative fuel sources. The regime’s designs for such engines may include a reactor fueled by HEU (four of the six navies in the world that possess nuclear propulsion reactors use HEU). Currently, the JCPOA prohibits Iran from producing HEU for propulsion purposes.

Last year, Tehran began reemphasizing the project in the wake of President Trump’s pressure policies, taking a step forward by alerting the International Atomic Energy Agency of its decision “to construct naval nuclear propulsion in the future.” To be sure, it told the agency that no facility will be involved in the project for the next five years; moreover, any such efforts would face immense economic and technological obstacles. Yet Tehran could still use the project to deter the West without breaching the deal—for example, by changing its declaration to the IAEA overnight and announcing that concrete progress will be made on the project in the near future.

Taking all permissible steps to restart the nuclear program quickly. Since the JCPOA was first implemented, Iranian officials have repeatedly noted Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s directive to prepare the nuclear program for a quick rebound in case Iran leaves the deal. Salehi became more specific about such efforts in his January 22 remarks, however, explaining that the AEOI has made the necessary preparations to resume enrichment in greater capacity, and that it will store more than thirty tons of yellowcake at the uranium conversion facility in Isfahan. Iran then followed through on the latter pledge earlier today—a crucial step toward ensuring that it has enough raw material if the deal collapses. At the same time, though, it would likely face significant technical challenges in restarting the program, similar to those it faced before the JCPOA.

Salehi has also reassured Iranian media that Tehran tricked the West by importing metal tubes similar to the Arak reactor tubes that were filled with cement under the nuclear deal—a concession highly criticized by hardliners at the time. These purchases were apparently made before JCPOA implementation, so they are not violations despite breaching the spirit of the deal. In fact, Salehi implied that Tehran had reported the new tubes to the IAEA (the agency’s publicly available documents do not mention the matter).

Salehi has a track record of making dubious claims, yet his statements should still be examined carefully by the IAEA and foreign intelligence services. They should also be raised in the next meeting of the Joint Commission, the body responsible for discussing JCPOA implementation issues.

Glorifying small nuclear advancements. Iranian officials have occasionally exaggerated minor nuclear improvements in order to convince hardliners and the wider public that the program is advancing despite the JCPOA. In April 2018, the regime unveiled no less than eighty-three new nuclear projects during its “National Nuclear Technology Day,” but most of them were insignificant from a proliferation perspective. As Iran approaches the Islamic Revolution’s fortieth anniversary celebrations in February, one can expect similar announcements aimed at rallying the public around the flag of nuclear “resistance,” including claims of advanced centrifuge improvements, inauguration of new uranium mines, and plans to construct new reactors.

Intentionally breaching the JCPOA by “accidentally” accumulating excess nuclear materials. In a November interview with the International Crisis Group, an unnamed senior Iranian diplomat stated that if the regime “had retaliated against the slow pace of sanctions relief with over-production of enriched uranium,” then Europe would have been more proactive in assisting Tehran. Following this logic, Iran could decide to play hardball, pressuring Europe by producing excess nuclear materials while claiming it did so unintentionally. Unlike the previous scenarios, this would constitute a clear breach of the JCPOA.

For example, Iran is required to keep its stock of 3.67% enriched uranium under 300 kilograms, but if it deliberately exceeded this limit, it could credibly blame the infringement on small technical errors inherent in the delicate, complex process of enriching uranium. Similarly, its permitted stock of heavy water is 130 metric tonnes, but unlike the uranium restriction, this limit is only an estimate, and the regime has already surpassed it in the past. If Tehran once again over-produces heavy water for its reactors, it could offer a number of technical excuses for the lapse. Such infringements would present Europe with a dilemma: should it remain silent about Iran’s blatant JCPOA violations and keep the deal alive, or retaliate harshly (as some European officials have said they will) and risk broader escalation?

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

By embracing incremental progress and toeing the international community’s shifting redlines, Tehran has cleverly advanced its nuclear program over the past few decades. Yet this strategy of exploiting loopholes and building a narrative of resistance around its nuclear activities has also inflicted great hardships on the Islamic Republic and its public.

Accordingly, doubling down on nuclear brinkmanship in the coming months could be a double-edged sword for Tehran. At a time when European officials have been stung by reports of Iranian terrorist and espionage activities on the continent, they may no longer sympathize with Tehran’s position or tolerate its games, even if they still aspire to keep the deal alive. President Trump has been looking to reunite the Western coalition against Iran, and the regime also faces numerous economic and political challenges at home, so playing hardball in the near term may prove detrimental to its goals.

Omer Carmi is director of intelligence at the Israeli cybersecurity firm Sixgill. Previously, he led IDF analytical and research efforts pertaining to the Middle East.