- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3016

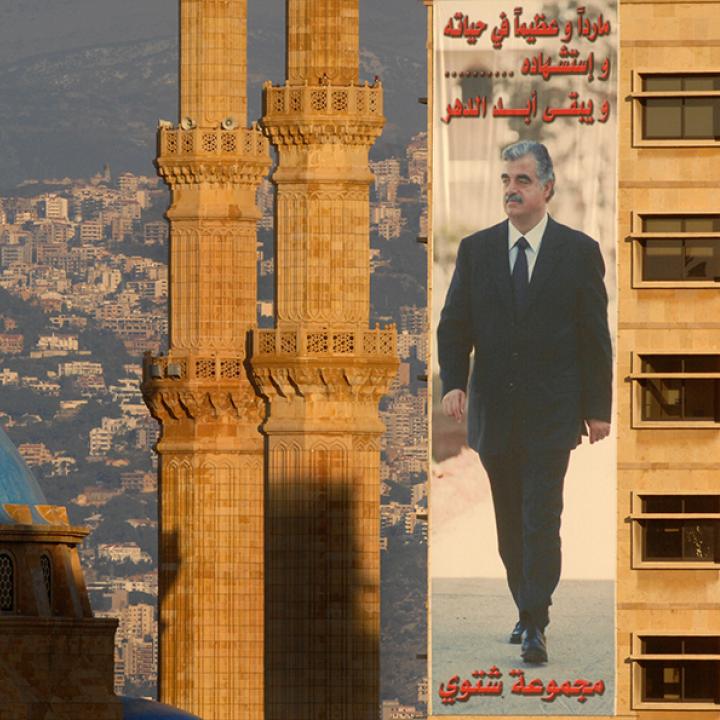

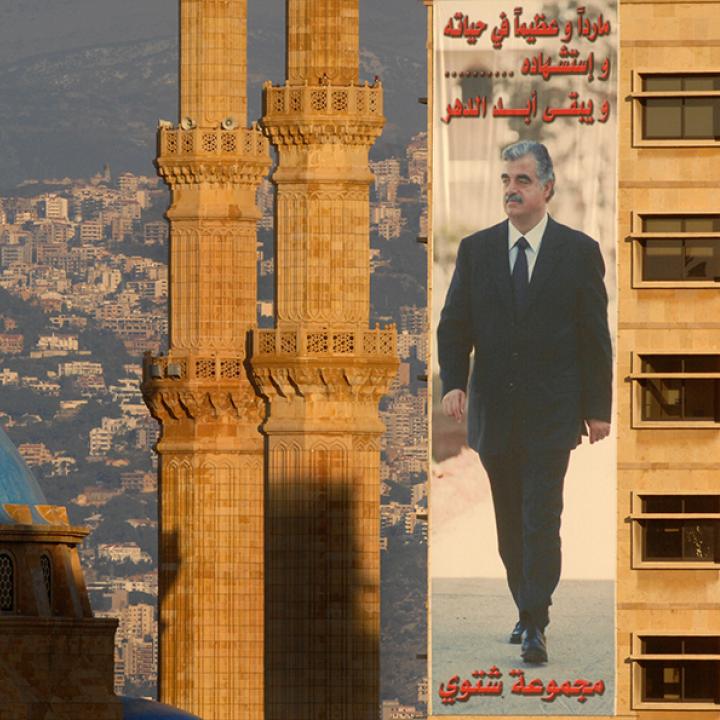

Prosecution Highlights Hezbollah, Syrian Links to Hariri Assassination

This week’s closing arguments laid out the clear connections between the plotters, senior Hezbollah figures, and the Assad regime, so the international community can no longer afford to look the other way.

Thirteen years after former prime minister Rafiq Hariri was assassinated by a car bomb in Beirut, the prosecution finally submitted its closing arguments in the Special Tribunal for Lebanon earlier this week, with two important disclosures. One, there is ample evidence to corroborate the link between Hezbollah’s leadership and the perpetrators of the killing, including details on their movements and communications ahead of the attack. Two, the Syrian regime was also at the core of the plot.

THE HEZBOLLAH CONNECTION

The closing arguments (released online as two PDFs, see part 1 and part 2) focused on the group’s links to the four accused, Salim Jamil Ayyash, Hassan Habib Merhi, Assad Hassan Sabra, and Hussein Hassan Oneissi. According to the prosecutor, Hezbollah secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah has repeatedly acknowledged this connection, including the fact that the covert Green Network used by the defendants was in fact part of the Hezbollah security apparatus.

Telecom data was the main evidence used to prove these links, coupled with the political context of the time and the political affiliation of the accused. In all, the prosecution examined more than 3,000 pieces of evidence and 307 witness testimonies before concluding that the February 2005 attack was executed as part of a sophisticated, multifaceted mission that could only have been the product of a conspiracy.

One of the main advances the prosecution has made is in showing how Hariri’s movements were under surveillance during and after his famous December 2004 visit to Nasrallah in the Beirut suburb of Haret Hreik—this despite the fact that neither Hariri nor his security team knew the location of the meeting beforehand. Yet this week’s most striking revelation was the reference to Hezbollah security chief Wafiq Safa, who apparently served as the group’s link with the Syrian regime. According to the prosecutor, Safa “formed part of a call flow with [senior Hezbollah military official Mustafa] Badreddine and Ayyash that immediately preceded the final preparatory activity in the early hours of the morning of the attack.” And on the eve of the assassination, Safa and Badreddine’s phones converged in the same area. In addition, Ayyash coordinated with Badreddine on conducting preoperational surveillance of Hariri and purchasing the Mitsubishi Canter van used to perpetrate the bombing.

THE SYRIAN CONNECTION

Rustum Ghazaleh, the head of Syrian military intelligence in Lebanon at the time, visited Haret Hreik often and was in regular touch with Safa, and the prosecution argued that this activity began under very specific circumstances: after the February 2005 Lebanese opposition meeting at the Bristol Hotel in Beirut, where participants demanded an end to Syria’s military occupation. The report noted that Ghazaleh’s visits and Hezbollah contacts formed part of a pattern of behavior immediately following key challenges to Syrian control in Lebanon, and immediately prior to Hariri’s assassination that same month.

“When put in context with these events,” the prosecution concluded, “the rationale and motivation behind the behavior of the networks becomes evident.” Indeed, the motives and actions of Syrian and Hezbollah officials were intimately connected at the time, and the corresponding reaction of covert networks involved in the plot reinforces the conclusion that they were operated by a single entity, coordinated by the accused and overseen by Badreddine.

NEXT STEPS

Although the final verdict is not expected for another five to six months, the revelations in the prosecutor’s closing arguments should not be taken lightly by Lebanon or the international community. If found guilty by the tribunal for killing a prime minister, Hezbollah will be regarded as a criminal organization by countries worldwide. This includes European governments, which will find it more difficult to deal with Hezbollah’s “political wing” if an international court officially determines that its parent organization carried out the assassination. In fact, such a finding should finally spur them to designate Hezbollah in its entirety as a terrorist organization rather than perpetuating the untenable “wings” approach.

Likewise, international relations with Lebanon’s state institutions will become highly problematic if Hezbollah remains part of the government. In 2004, UN Security Council Resolution 1559 called on Syria to withdraw its forces and cease interfering in Lebanon’s internal politics. Although Damascus largely complied with that requirement, the second part of the resolution—which calls on all Lebanese and non-Lebanese militias to disband—has yet to be implemented. Other long-postponed requirements were issued in Resolution 1701, which called for border demarcation between Syria and Lebanon.

Perhaps sensing potential progress on these fronts, Nasrallah warned the tribunal and its backers not to “play with fire” in an August 27 address. Whenever Hezbollah makes such threats, decisionmakers inside and outside Lebanon tend to give the group what it wants for fear of causing local instability. There are numerous examples of this appeasement, such as the electoral law that facilitated the victory of Hezbollah’s camp in this year’s parliamentary elections, or the events of May 2008, when the group used its weapons against other Lebanese citizens and wound up with a national unity government and the Doha agreement.

This time, however, the charges against Hezbollah will be coming from an international entity, and foreign governments should deal with them forthrightly rather than ducking them. The United States and other countries need not be cowed by the specter of instability—on the contrary, allowing Hezbollah to get away with Hariri’s murder would only agitate sectarian tensions, the true driver of instability across the region.

Specifically, Washington and European governments should be prepared to delay their acceptance of any new Lebanese government that includes Hezbollah figures, particularly in the security realm. They should also question Beirut about any perceived Hezbollah influence on these decisions. Prime Minister Saad Hariri needs strong, united international support to resist the group’s intimidation. To protect Lebanese state institutions, Hezbollah must be kept at a distance, and this requires close coordination.

Finally, the revelations about Syria’s role in the assassination should put an end to the notion that Bashar al-Assad can be part of his country’s political future. Even if Western and Arab governments were willing to overlook his brutal actions against his own people, there must be consequences for his regime being legally implicated in the killing of a foreign political leader.

Hanin Ghaddar, a veteran Lebanese journalist and researcher, is the Friedmann Visiting Fellow at The Washington Institute.