- Policy Analysis

- Interviews and Presentations

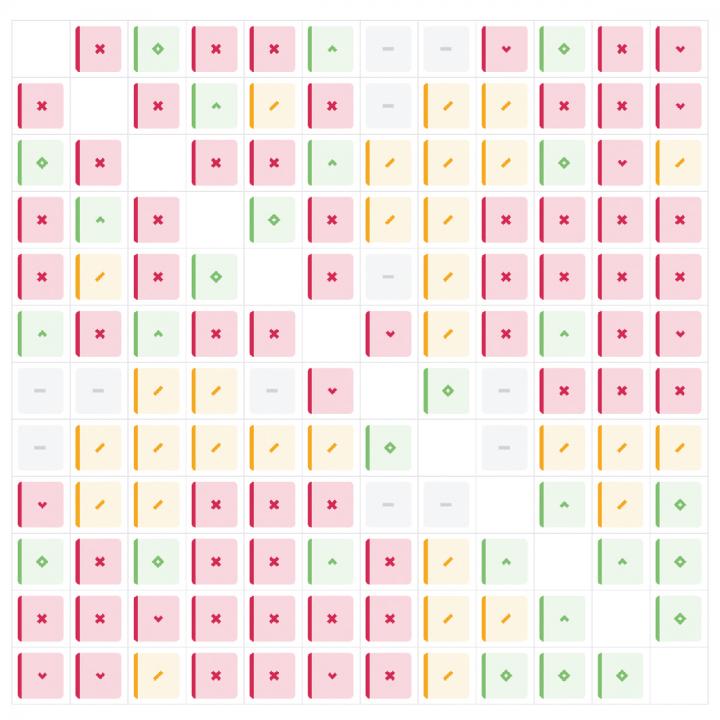

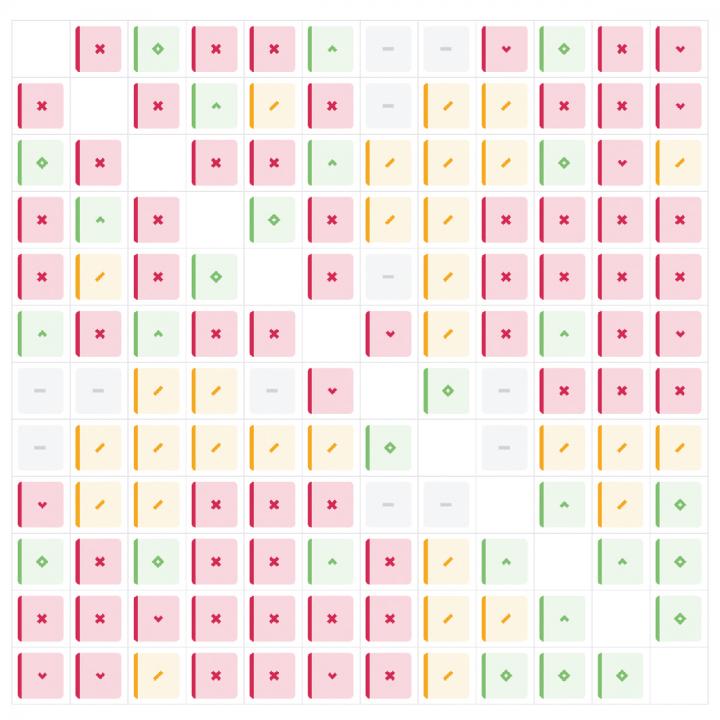

Yemen Matrix: Allies & Adversaries

The Yemen matrix is no longer being actively updated as of March 2022.

The Yemen Matrix is a guide to the relationships between the core actors involved in the country’s various conflicts. It is meant to be a starter resource for new analysts, a quick-access volume for policymakers, and a refresher for experts.

Introduction

To fresh eyes, the current conflict in Yemen may appear to have begun when a rebel group solidified its takeover of the capital in 2015, leaving the government to flee into exile and its regional neighbors scrambling to save it. Yet that story line only scratches the surface. Yemen is not a single story; instead, it is a complex web of stories. It is what some Yemenis call a soap opera (better known in Yemen as musalsal turki). Indeed, like a soap opera, the story of Yemen is defined by complex relationships, shocking events, ever-changing incentives, and unexpected partnerships—all of which have too often and for decades created instability and uncertainty for the Yemeni people.

Suffice it to say, the plotlines visible in Yemen today did not begin in 2015, and most will not end when the current war concludes. In fact, many Yemenis express concern that their compatriots are already writing the script for the next season in Yemen’s story while this season still plays out. This should be cause for concern for more than just Yemenis. Yemen sits alongside key waterways for global trade, has served as a haven for al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and has kept the Gulf region embroiled in conflict since 2015. Its complexity doubles as instability. To nudge Yemen toward stability requires a concerted effort and deep understanding of the relationships at play there.

Those new to the Yemen portfolio often find themselves confused by the web of relationships. To start, Yemen is a country of about 30 million people, but one where every Yemeni inexplicably seems to know every other. It is a place where the personalities drive events more than institutions, and where informal influence is often more potent than formal power. It is a country with an acute memory, where the events of 1962, 1986, 1994, and 2004 are still as much in play as events of today. The Houthis no doubt remember who was against them in the Saada wars of 2004–10 (e.g., Gen. Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, Islah). Those in the Southern Transitional Council (STC) remember who fought against secession in 1994 (e.g., Ali Mohsen, President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi, Islah, the General People’s Congress, the Saleh family), but also those who supported them at least notionally (e.g., Saudi Arabia). In the future, the actors in today’s Yemen will recall who fought with and against them in this war.

These often visceral recollections help explain why, more frequently than not, grievance is at the heart of decisions and relationships in Yemen. Even when new political organizations pop up (e.g., the STC in 2017), they are often new faces for old grievances. Making them all the more potent, these gripes are not based on lore; rather, they have accumulated within the lifetimes of those involved. Yemenis alive today in both the north and south lost family members in the wars of 1962, 1986, 1994, and 2004, for example, and they hold other actors responsible. These wars, like all wars, have created adversaries more often than they have spurred a sense of common interest. In fact, the common interest between actors often is their common adversary. As a result, if one is trying to understand why an alliance exists in Yemen, it is often best to start with common adversaries or shared grievances.

For example, the Houthi invasion of the south was a watershed for the Hadi government and the STC. For the Hadi government, it was yet another symbol of the Houthi coup against it; for the individuals who would eventually form the STC, it was yet another northern invasion of the south. This shared sense of injustice aligned the two temporarily against the Houthis, yet their own enmity for each other—born of events in 1986, 1994, and after—simmered underneath and eventually emerged violently.

Given the number of adversarial relationships in Yemen, groups often choose the lesser of two enemies to work with against the greater enemy. It is the classic strategy epitomized in “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Or as Yemenis like to say, “My brother and me against my cousin. My cousin and me against the foreigner.” This can be confusing to new analysts but becomes clearer if one applies the adversary-centric lens.

In the current war, for example, using the term “pro-government forces” would suggest an affinity within those forces, when in reality few forces fighting the Houthis are actually pro-government; they are, instead, anti-Houthi. Their alignment with the government is shaky at best, as evidenced by the STC and Tariq Saleh’s forces refusing to report through a chain of command led by the government. Similarly, many of those aligned with the Houthis are not pro-Houthi but rather anti-Saudi.

This tendency to rank adversaries and team up accordingly creates strange bedfellows—like Ali Mohsen with the Arab Spring protestors, the STC with the Hadi government, or, perhaps strangest of all, the late former president Ali Abdullah Saleh with the Houthis. But it also clearly indicates to analysts and policymakers what splits are likely to occur when the common adversary or grievance is removed.

Just as aligned actors cannot be assumed to share interests beyond a common enemy, opponents are not always divided eternally by hatred. Onetime adversaries such as the Houthis and former president Saleh have been known to align with each other, only to split again. Similarly, allies are known to become adversaries, as happened with the STC and the Hadi government, only to become allies of convenience again.

Grievance constitutes the historical lens through which Yemenis view the present, defining their relationships, shaping their perspectives, and driving their behavior. Facts are often hard to come by in Yemen—for example, asserting for certain who conducted a bombing—given the number of actors, the difficulties for journalists, and other contextual factors. Therefore, assessing perspective is often more useful in predicting the actions of groups or individuals. In August 2019, for example, the STC believed Islahis within the Hadi government were behind the killing of one of their senior commanders, even though the Houthis took credit for the attack. Many Yemen watchers, including this author, anticipated that perspective would drive behavior; indeed, it led to the STC entering into a conflict with the government and taking over the city of Aden.

If Yemeni-Yemeni relationships were not complex enough, a regional element is often present too. Many Yemeni actors rely on an outside patron for financial support—as the STC does with the United Arab Emirates, the Mahri protestors do with Oman, and the Houthis do with Iran. This matrix shows that the closest “alliances” in Yemen are usually with a foreign patron. Yet perhaps counterintuitively, most Yemeni groups express fiercely anti-foreign-interventionist sentiments. As a result, the relationships with foreign patrons are multidimensional: the financial resources aid Yemeni groups in pursuing their ambitions, but these groups guard their autonomy by not always following their patrons’ advice. It is rare for a group in Yemen to act as a full proxy for an external country—Hadi occasionally snubs Saudi Arabia, the Houthis have flouted Iranian advice, and the STC sometimes defies the UAE’s cautions.

Moreover, no group in Yemen is a monolith, and not every Yemeni in a group ascribes to the entirety of that group’s view. In fact, it is common for individual members to disagree with their group in some way. No one-size-fits-all approach works completely with Yemen. Even when a shared sense of purpose leads actors to align with each other against a common enemy, each group and each member within it remains fiercely independent.

Out of this complexity comes this project, which attempts to disentangle and explain the web of relationships in Yemen by taking a kaleidoscopic lens to them. It is meant to be concise without being vague, simple without oversimplifying, informative but not exhaustive. It is, of course, impossible to put any country or any set of relationships into a series of boxes with icons and call it comprehensive, let alone definitive. In fact, it is likely no two Yemen experts would agree on the exact icon to put in each box given the nuance in every relationship. But, for new Yemen analysts or for policymakers who are regularly confounded when sifting through the muddy waters of Yemeni relationships, this project seeks to clarify and inform. For Yemen experts, it should spur conversation as well as provide a tool shared among stakeholders that allows for more in-depth and nuanced conversations. This project is a mere toe in the water for explaining the multifaceted country of Yemen, but the hope is that it will make the subtleties of Yemen more accessible to policymakers.

Project Mechanics

The Yemen Matrix is a guide to the relationships between the core actors involved in the country’s various conflicts. It is meant to be a starter resource for new analysts, a quick-access volume for policymakers, and a refresher for experts.

Story Line Concept

Learning any new subject area can be arduous, but this is especially so when the learning curve is as steep as it is in Yemen. Like a soap opera or complex TV drama, Yemen has a wide-ranging, fiercely independent cast of characters with interwoven relationships and multiple plotlines unfolding at once. In these situations, story arcs are effective tools for conveying the basics quickly. For example, if someone learns that the Houthis believe Ali Mohsen gave the order to kill their leader, Hussein Badr al-Din al-Houthi, in 2004, they immediately and viscerally grasp one side of that relationship without knowing any of the other multiple details in their history. Those details come in time.

A story also allows those new to the Yemen portfolio to connect with the actors, just as one does with characters in a well-written novel or TV show. Story lines are a way of humanizing the Yemeni experience, creating memorable impressions, and telling the history of Yemen through the people and groups who experienced it, rather than doing so as a series of faceless historical timelines and academic postulations. The American writer Kurt Vonnegut emphasized the power of story arcs because, as a reflection of our own lives, all humans know them by heart. Thus, finding the story arcs that exist in Yemen among the main actors can be an effective way of concisely depicting Yemen’s complexity.

Unlike TV dramas or soap operas, this project does not dramatize or sensationalize events or relationships for the sake of crafting a good story. Yet much of Yemen’s history is dramatic anyway. The story of the 1986 civil war in the south, for example, reads as if straight out of a dark novel.

Methodology

This matrix is the result of years of tracking Yemen and its wide-ranging cast of characters. Much of the information in this project, especially the nuance and detail, comes from conversations with the actors themselves, including at the leadership, middle, and “street” levels. This project is, in short, a collection of perspectives as interpreted by the author. The perspectives that actors have of each other form their relationships, and deciphering those relationships helps one make sense of events in Yemen.

Of course, any attempt to simplify relationships as complex as those in Yemen into a series of icons will never be comprehensive, nor definitive, but it should be instructive. To keep it straightforward and user-friendly, the project has a word limit for all aspects, including profiles and relationship descriptions, as well as the number of select members and events.

Project Components

In keeping with the story line concept, this project centers on two components: the cast of characters and the relationships among them. The cast of characters section begins with a maps page and follows with a page for each actor that includes a concise profile, a select list of members (for groups), and the relationships. For each relationship, an icon denotes its place along the spectrum from ally to adversary, accompanied by a brief explanation and a few select events that have influenced it.

The Cast of Characters

The project includes twelve actors: four countries, one person, and seven groups of varied cohesiveness.

The four countries are key regional actors with a link to Yemen’s current war and its players: Iran, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. They are by no means the only regional states with an interest in Yemen. An expanded project could include Qatar or perhaps even Turkey, especially if their interest and influence continue to grow. These two states have particular influence over offshoots of Islah, which remain active.

The person singled out in the project is Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, a preeminent figure in Yemeni politics whose complex history requires his relationships to be examined on their own. If former president Ali Abdullah Saleh or Sheikh Abdullah al-Ahmar, the late head of the Hashid tribal confederation, were still alive, either would be treated similarly—as an individual whose personal command was great enough to have his own slot in this project.

The seven groups in the project include the two main actors in the war (the Houthis and the Hadi government); the two main political parties (Islah and the General People’s Congress [GPC]); the still-relevant and influential Saleh family, named after the late president of Yemen, who served for thirty-three years; the Southern Transitional Council (STC), which has made a name for itself in the south; and the Mahri protestors, who arose in opposition to Saudi Arabia’s presence in their province on Yemen’s border with Oman.

Dealing with Splinters

Some political parties, such as Islah and the GPC, have splintered because of the war. Rather than covering all the factions, which remain difficult to precisely parse, this project includes only the core of each political party.

Thus, when this project refers to Islah-Riyadh, it refers to the faction of the Islah Party currently residing in Riyadh and led by those elected to leadership, namely Mohammed Abdullah al-Yadoumi and Abdulwahab Ahmed al-Ansi. Others based around the region in Cairo, Amman, and elsewhere accept this leadership. If this core faction is defined by its alignment with the coalition, other Islahis (not represented in this project) are defined by their opposition to the coalition. These individuals—many of whom have been formally dismissed from the core party—tend to be more closely aligned with the transnational Muslim Brotherhood and to reside in Turkey, Qatar, and Oman. These anti-coalition Islahis are important, even if they do not form a cohesive group, and they should be known to Yemen watchers given that they will play a role in the country’s future. An expanded version of this project could take account of this assemblage, especially if they coalesce.

When this project refers to the GPC-Sanaa, it means the core party in Sanaa aligned with the Houthis. Several GPC members living outside Yemen—many with no affinity for the Houthis—aspire to rejoin and rebuild the party in the eventual aftermath of the war, including several individuals in Muscat, Cairo, and Abu Dhabi, but they are not counted among the GPC-Sanaa cohort in this project. If the GPC in Sanaa is defined by its opposition to the coalition, other party adherents outside Sanaa are defined by their alignment with the coalition or the Hadi government. The coalition-aligned GPC members, however, have not created a cohesive alternative GPC Party and often act in their own capacities instead (e.g., as a governor, a military figure).

Other Complications

Although the Saleh family was the mainstay of the GPC Party for three decades when Ali Abdullah Saleh was alive, the family’s relationship with the party has become quite complicated since the Houthis killed Saleh in December 2017. Thus, the family is treated separately from the GPC-Sanaa in this project.

A map accompanying each character icon shows that many groups included in this project have representation in Yemen as well as in the regional capitals of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Oman. For example, the Houthis, the GPC-Sanaa, and Mahri protestors have representatives in Muscat; Islah-Riyadh and the Hadi government in Riyadh; and the STC and the Saleh family in Abu Dhabi. Some groups have their leadership primarily based in Yemen with representatives elsewhere, while other groups have the inverse setup.

Groups Not Included

There were several groups considered but ultimately not included in the project.

Al-Ahmar Family: The al-Ahmar family would have been included in a project like this prior to the current war; the family, however, has lost collective influence since Sheikh Abdullah al-Ahmar died in 2007 and the Houthis overran its strongholds and burned its family home in 2014. Their lack of inclusion does not negate the possibility that they will return to importance and influence in the future.

Salafist Groups: Also absent are Salafist groups, of which there are many. Given the nature of Salafism, no core group exists. Instead, Salafists are present in different forms among the STC, the Houthis, the Red Sea coast forces, Islah, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Islamic State (IS), and elsewhere. If they coalesce into distinct groups, they may merit future inclusion.

Red Sea Forces: The Red Sea forces—including various brigades, the Tihama Resistance forces, and even Tariq Saleh’s forces—are not included. However, Tariq’s perspective is captured under the Saleh family, the Amaleqa Brigades fall under the Salafist category defined above, and others fall under the Hadi government’s command. The Red Sea remains an area to watch closely, but in general this project has avoided including military brigades in the cast of characters.

Tribes: The project also omits individual tribes, although many merit a close watch and are influential, including the Murad and Abida tribes of Marib, the Yafa tribe, the Awaliq tribes of Shabwa, the Hajour tribes of Hajjah, and others.

Terrorist Groups: Finally, terrorist groups such as AQAP and IS are not included, in large part because they are broadly opposed by every other actor and thus do not make for an informative relationship map. Certain groups in Yemen face regular allegations of cooperating with terrorist elements, but all actors in this project condemn terrorism in their public statements.

Actor Profile

The profile tells the history of the actor as concisely as possible with particular reference, where possible, to the other actors and select events noted in the relationships section.

Select Members

The select members section is an ancillary short list of the most influential, discussed, commonly cited, or well-known members of a group. It is not meant to be—and is far from—an exhaustive list. Nor is it an ordered rank, or a list of those with the most important titles. Note that individual Yemenis often break with the party line, so not all views ascribed to a group can be ascribed to individual members.

The Relationships

The project includes five main types of relationships on a spectrum from “allies” to “adversaries,” with “favorable,” “complicated,” and “unfavorable” between these poles.

Relationships are not stagnant and will move along the spectrum defined above, sometimes tipping more toward allies or more toward adversaries. This matrix attempts to be as timeless as possible. It will not capture the day-to-day nature of those variations but rather the broad nature of the relationship.

For example, the STC and the Hadi government are cited as “unfavorable.” There are moments when the two actors have been actively at war with each other, suggesting a move down the spectrum toward adversaries. Upon implementation of the Riyadh Agreement, they could move up the spectrum closer to complicated. Despite these occasional shifts, broadly speaking they have an adversarial relationship with at least one reason to cooperate (they are both part of the coalition against the Houthis); thus, their relationship is categorized as unfavorable.

In other cases, relationships do markedly change such that the matrix would require an update.

For example, the Saleh family’s relationship with the Houthis took a decisive turn when the Houthis killed the family patriarch in 2017. Tariq Saleh consequently switched sides in the war.

Relationships are inherently difficult to define when public expressions differ from private sentiments. This is most often relevant for countries, which can have a public position that differs from the day-to-day experience of their officials. In these cases, the matrix generally defaults to the actor’s public position since that is the one most relevant to policymakers; however, in these cases, the relationship description will allude to the private views.

The Hadi government–UAE relationship is a case in point. The UAE has a negative view of the Hadi government given its track record of mismanagement and its ties to Islah; meanwhile, the Hadi government is incensed that the UAE has financed groups, such as the STC, that compete for its legitimacy. Moreover, the government believes the UAE intentionally bombed its forces in an August 2019 operation that the UAE defends as a counterterrorism move. Despite these significant disagreements, the two are part of the anti-Houthi coalition and the UAE publicly supports the Hadi government’s legitimacy.

In another example, the Omani government has a friendly relationship with actors it hosts in Muscat, including the Houthis. But the project denotes its relationships with most actors as “complicated” rather than “favorable” because it officially takes a neutral position on the war.

In other cases, two actors may be part of a public alliance that is indeed quite messy behind the scenes. In these tricky cases, where reasonable experts could disagree on their placement on the spectrum, the author has made a judgment call.

For example, the Houthis and the GPC are aligned in the war against the coalition but have an increasingly strained relationship. Some may argue they are “allies,” while others may argue the situation is “complicated.” This project labels their relationship as leaning favorable given that they are aligned in a war together but with some complications.

The author often made these judgment calls by comparing the relationship in question to other relationships already denoted. The relationships, in other words, were determined relative to each other.

Making the project trickier still, relationships are often defined differently by the two actors in question. For example, Actor A may dislike Actor B more than Actor B dislikes Actor A. In these cases, the relationship tends to capture the stronger view and denotes the imbalance in the relationship description.

Finally, the project uses the “no relationship of note” descriptor sparingly but deliberately. This sometimes means there is no relationship at all but more often means there is no notable relationship.

For example, Ali Mohsen and Gen. Ali Salem al-Hurayzi, the face of the Mahri protest movement, know each other from when they worked in the Saleh administration, but Ali Mohsen is not actively involved in a public way to either support or oppose the Mahri protest movement. Thus, the Ali Mohsen–Mahri protestors relationship is categorized as “no relationship of note.”

Relationship Description

The relationship descriptions are minimalist by design. The author took the entire relationship into account when deciding on the taxonomy, but the write-up of the description sticks to the simplest explanation possible. For example, relationships like Ali Mohsen–Saleh family or GPC-Islah are decades deep, yet they are explained simply in terms of their current connection to the war in Yemen. All readers who wish to become Yemen specialists should dive deeper into these historical relationships.

Select Events

The select events are an ancillary aimed at directing the reader’s attention to those key historical events that every Yemeni knows, often personally remembers, and that underpin many of the relationships the project highlights. The author chose events that occurred within the lifetimes of most Yemenis today. Events such as the 1962 North Yemen Civil War or the 1967 British withdrawal from South Yemen are foundational to understanding how Yemen arrived at its current situation, but the timeline is limited to those events closer in memory and more often invoked when describing modern-day relationships.

These events were sometimes a turning point in a relationship; other times they only solidified an existing relationship. The list is not meant to be—and is far from—exhaustive, but these events are essential to understanding Yemen today. Like other parts of this project, word limits were imposed, so the descriptions are instructive but not exhaustive; instead, they are written to give just enough context to understand how the event applies to the relationships it shaped.