- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3993

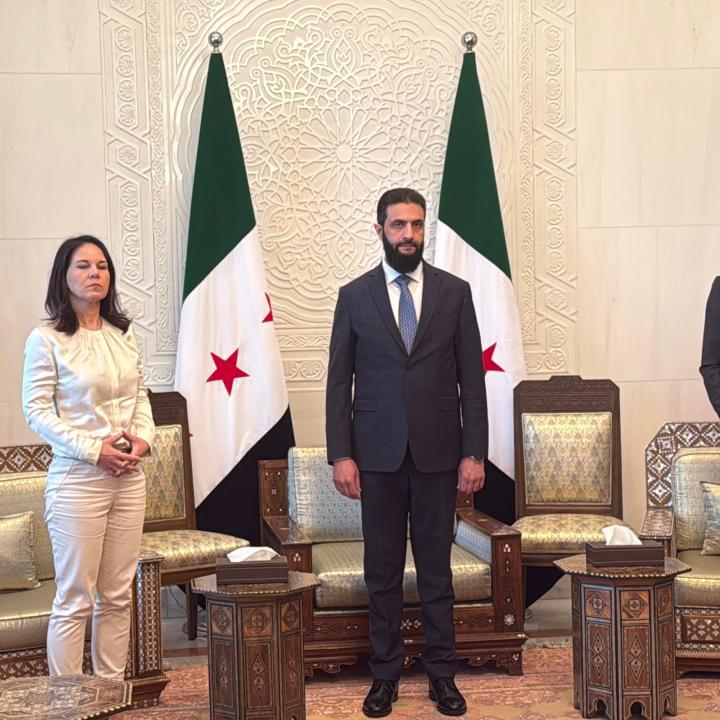

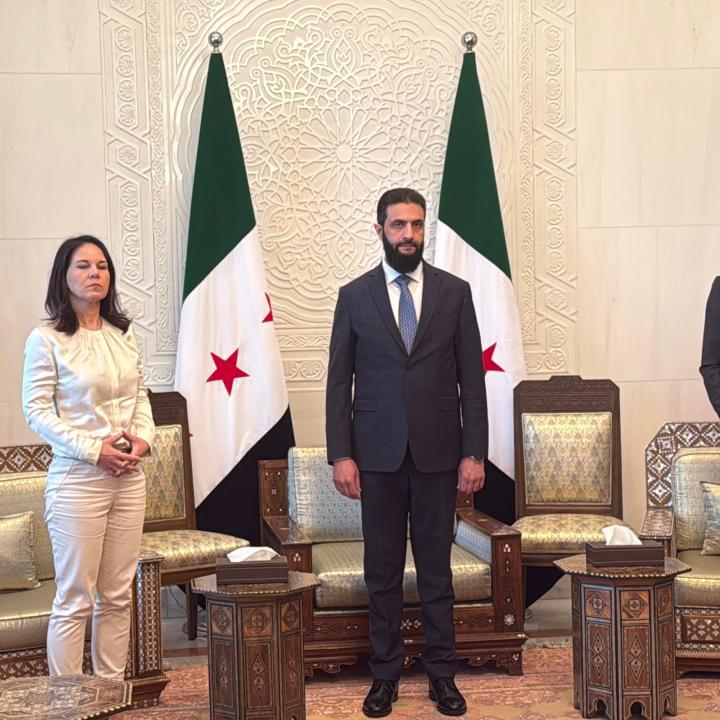

The Paris Conference on Syria: Coordination and a Roadmap Are Needed

To set up a future where U.S. forces and constant U.S. attention are no longer needed in Syria, Washington must be involved now, and smart transatlantic engagement could facilitate this goal.

The international conference on Syria, to be held in Paris on February 13, will be the first gathering of international actors since the Trump administration took office, and the third conference of its kind since the fall of the Assad regime, following Aqaba and Riyadh. The agenda of the conference, which will be attended by numerous regional and international foreign ministers, including Syria’s, will focus on political transition, humanitarian aid, and rebuilding. Yet all eyes are on the Trump administration, since the conference comes as Washington has signaled skepticism toward ongoing engagement in Syria. The country’s transition—and the gathering in Paris—present the United States and its allies with an opportunity to create a roadmap with benchmarks for stabilizing Syria, and by extension the Middle East. In so doing, Washington can help set up a future without the need for U.S. forces in Syria or constant U.S. attention.

Different Actors, Different Agendas

After five decades of authoritarianism and more than a decade of civil war, the fall of the Assad regime has created both optimism and uncertainty. Since December, countries inside and outside the region have exercised their interests in Syria, often centered on stemming the flow of Captagon, terrorism, Iranian influence, and instability that have long spread from the country’s borders. Turkey’s agenda of defeating its nemesis, the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), led it to support the uprising by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and encourage Ankara’s local partners—the militias that make up the Syrian National Army—to change the realities on the ground, moving deeper into the country to push back the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Meanwhile, Israeli airstrikes targeted Bashar al-Assad’s military, while the Biden administration expanded its operations against the Islamic State (IS) to areas formerly held by the regime. Others, including the Gulf countries, sought to engage with Syria’s new authorities, presumably to counter the Iranian influence that flourished under Assad. Indeed, the transitional government appears particularly open to Gulf engagement, with President Ahmed al-Sharaa making Saudi Arabia his first international visit. For the European Union and United Kingdom, Syria’s long civil war brought major consequences that included mass-casualty terrorist attacks and over a million refugees, so they tend to see the emergence of new rulers as a chance to rebuild the country and counter the IS threat.

While these and other actors have diverse interests in Syria’s future, the Paris conference offers an opportunity to move past the post-Assad honeymoon period to create concrete benchmarks for success and a roadmap for a stable Syria. The task will not be easy, since perception gaps are wide. Among regional actors, the most optimistic countries (Qatar and Turkey) are urging the international community to support the transitional government before asking for proof of its good faith; in contrast, the suspicious camp (Egypt and Jordan) remains prudent, and the pragmatic camp (the United Arab Emirates) is apparently taking a “wait and see” approach. In Europe, the discussion is still ongoing between the most risk-tolerant countries—who have welcomed large numbers of refugees and would like to see a general lifting of sanctions to hasten their return to Syria (e.g., Austria)—and the most watchful countries, who insist that the EU should be cautious and propose only reversible measures (e.g., Cyprus).

Syria’s Request for Assistance

The interests of Syrians themselves are likewise diverse. The transitional government has called for national unity and has first and foremost asked for the lifting of sanctions, with caretaker foreign minister Assad al-Shaibani even linking sanctions relief to handling of the transition. The new leadership has said the right things (e.g., emphasizing inclusion, calling for unity and diaspora participation), but much uncertainty remains about their intentions on the ground, including in the northeast. Civil society organizations have made it clear that the heavy-handed HTS method of governance in Idlib cannot be applied to all of Syria. Moreover, many Syrians argue that transitional justice must be a central part of the entire conversation, and that the Paris conference should build on the “justice dialogue” held last month in Damascus by Syrian civil society organizations.

Complications Loom on Coordination

Bringing such a diverse group of actors together to set out a clear roadmap will not be an easy task, especially as NATO ally Turkey appears willing to sideline Europe in order to reach its main goal—defeating the PKK at home and abroad—while simultaneously increasing its influence in Syria. Ankara is less vocal today than in the past about its ability to take over the fight against IS in the northeast on its own. Yet President Recep Tayyip Erdogan may still try to convince President Trump that a grand bargain is possible—one in which all U.S. troops would simply have to leave so that a regional platform made up of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Jordan could step in and take the reins of the counter-IS fight and control of prisons in the northeast.

Ankara’s offer might sound tempting to the Trump administration, which has initiated the most far-reaching overhaul of U.S. foreign assistance in decades, is dismantling the principal U.S. agency responsible for extending this assistance, and has once again floated the idea of removing U.S. troops from Syria. Although the Defense Department has made plans for a possible withdrawal, the future of the U.S. presence remains unclear, as Secretary of State Marco Rubio also recently said, “If there is an opportunity in Syria to create a more stable place than what we’ve had historically...we need to pursue that opportunity and see where that leads.” U.S. ambiguity has created uncertainty for many in the international community, who want Washington to help guarantee that the IS threat in Syria does not spread.

The decision by many European and Middle Eastern countries not to complete the process of repatriating foreign fighters and families in Syrian territory further complicates the talks. Trump will likely reiterate previous calls to repatriate all foreign nationals held in the northeast. In France, as in other European countries previously targeted by IS-inspired terrorist attacks, it will be difficult to overcome domestic political opposition to bringing these individuals back home. Moreover, these transatlantic discussions are set against the backdrop of other contentious issues, including Trump’s statements about purchasing Greenland and the threat of tariffs on the EU.

Recommendations

France has stepped forward on Syrian coordination efforts. For the Paris conference to succeed, it should seek to be more than an international photo opportunity. Smart transatlantic engagement now will ensure a future in which Syria is stable and U.S. forces are no longer required. The following steps could facilitate this goal:

Transatlantic coordination. Despite the difficulties noted above, this is a pragmatic opportunity for Washington and its European allies to facilitate a transition that helps stabilize Syria and, by extension, the Middle East. For the Trump administration, the Paris conference offers a chance to proactively coordinate with partners to reach the administration’s strategic goals. A clear U.S. policy on Syria is the only way to ensure that actors such as Russia will not fill the gap left behind by Washington and its allies.

Sanctions. Lifting U.S. and EU sanctions without coordination—and without concrete benchmarks—would be a mistake. The process of easing sanctions has begun on both sides of the Atlantic. On January 6, the U.S. Treasury Department issued General License 24, which eased sanctions on Syrian transactions related to energy and personal remittances. On January 27, the EU announced a partial, gradual lifting of sectoral sanctions. The Paris meeting gives them an opportunity to coordinate these concrete benchmarks with other allies before the scheduled meeting of the EU Foreign Affairs Council on February 24. While the legal response will take time and the lifting of sanctions is a lengthy process, it is important for U.S. and EU decisions to produce clear and reasonable consequences within a feasible timeframe. U.S. and European officials should also help with rebuilding trust between Syria’s transitional government and the UN, as well as ending restrictions on aid from international financial institutions such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

Agreement with partners in northeast Syria. Like the United States and EU, Turkey seeks to stitch Syria back together into a more or less coherent whole that can serve as a stable neighbor. It should therefore remain a Western ally in Syria. However, the United States and EU countries also need to advance their own interests, which do not necessarily align with Ankara’s and include preventing Russia from regaining influence there. Accordingly, Washington and its European partners should double down on pushing for a Damascus-SDF reconciliation before leaving, since many allies worry that a U.S. withdrawal without proper planning and caution could have Afghanistan-like consequences. This reconciliation will be tricky to secure; negotiations currently seem to be stuck on the SDF’s continued bid for administrative autonomy. Yet it is not out of reach, and the talks should continue.

A roadmap and benchmarks. For the first time since the end of the Assad regime, neighbors, regional actors, Western countries, and the new Syrian authorities will be able to agree on a joint statement. A vague, noncommittal statement would certainly miss the point. Some actors are deservedly suspicious of the transitional government, and Damascus will need time to earn the full trust of the Syrian population and the international community. The Paris conference should be the moment when foreign actors move past the excitement surrounding Assad’s ouster and begin laying out their expectations. As Sharaa recently told the Economist, Syria under Assad was a source of concern for its neighbors and did not fulfill its basic duties toward the Syrian people. Many in Paris will be looking to the transitional government to lay out clear benchmarks for an inclusive government that adheres to the spirit of UN Security Council Resolution 2254 with a realistic timeline. These benchmarks should include:

- a call for an inclusive political process that encompasses Syrian civil society and the different components of the population, including the drafting of a new constitution

- a strategic plan to take appropriate counterterrorism actions against IS, al-Qaeda and its affiliates, and Iranian-associated armed groups

- a strong commitment to the destruction of the previous regime’s chemical weapons program, in close cooperation with the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons

- a strong commitment by the transitional government to dismantle the Captagon trade and prevent its resurgence

- a strong commitment to continue holding those responsible for regime crimes accountable, particularly crimes committed during the civil war

Transitional justice is a vital part of the reconstruction process, and one of the best ways to help build a stable new Syria that will no longer pose a threat to the region.

Devorah Margolin is the Blumenstein-Rosenbloom Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute. Souhire Medini is a visiting fellow at the Institute, in residence from the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs.